|

All authors draw upon a wide range of inspirations when creating their stories, such as real-life experiences, places they have visited, concerns about the world and society, books they have read. For me, visual art has always inspired and influenced my writing. I cannot claim to be an expert in art history, and as much as I enjoy sketching, my artistic skills are limited at best, but I find it an endlessly absorbing subject and a way of finding different perspectives on the world. By offering us a safe space to consider and explore feelings and fears we otherwise feel uncomfortable in confronting, art can help us all feel a little less alone in this world.

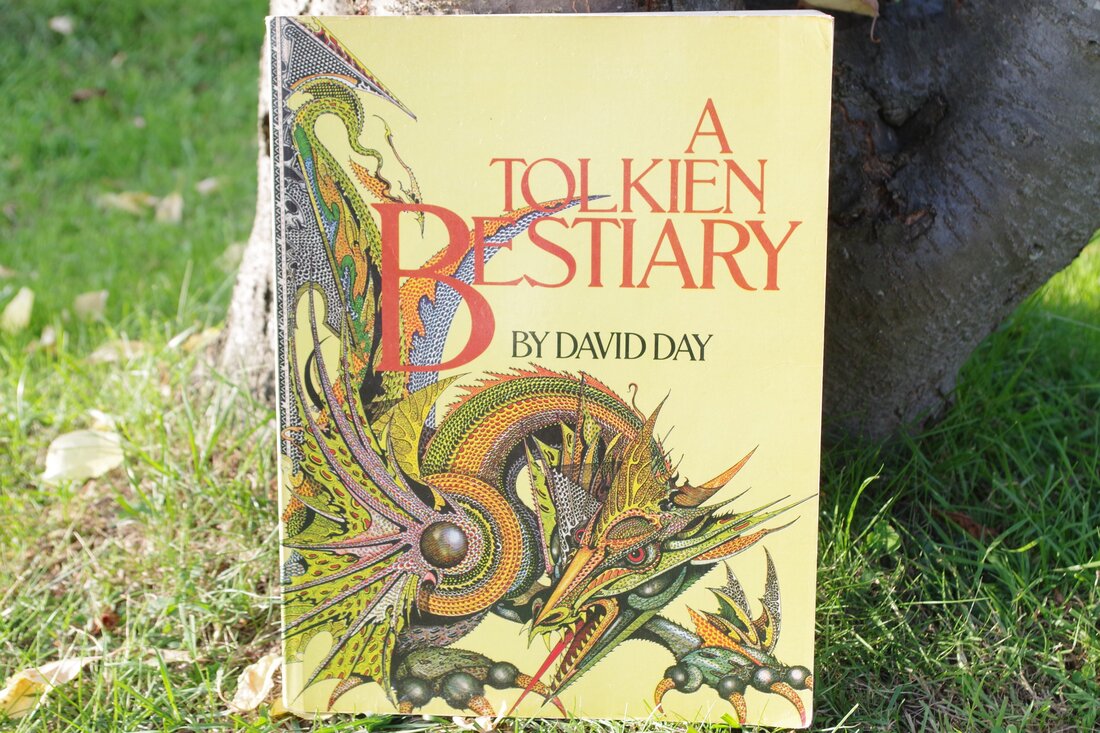

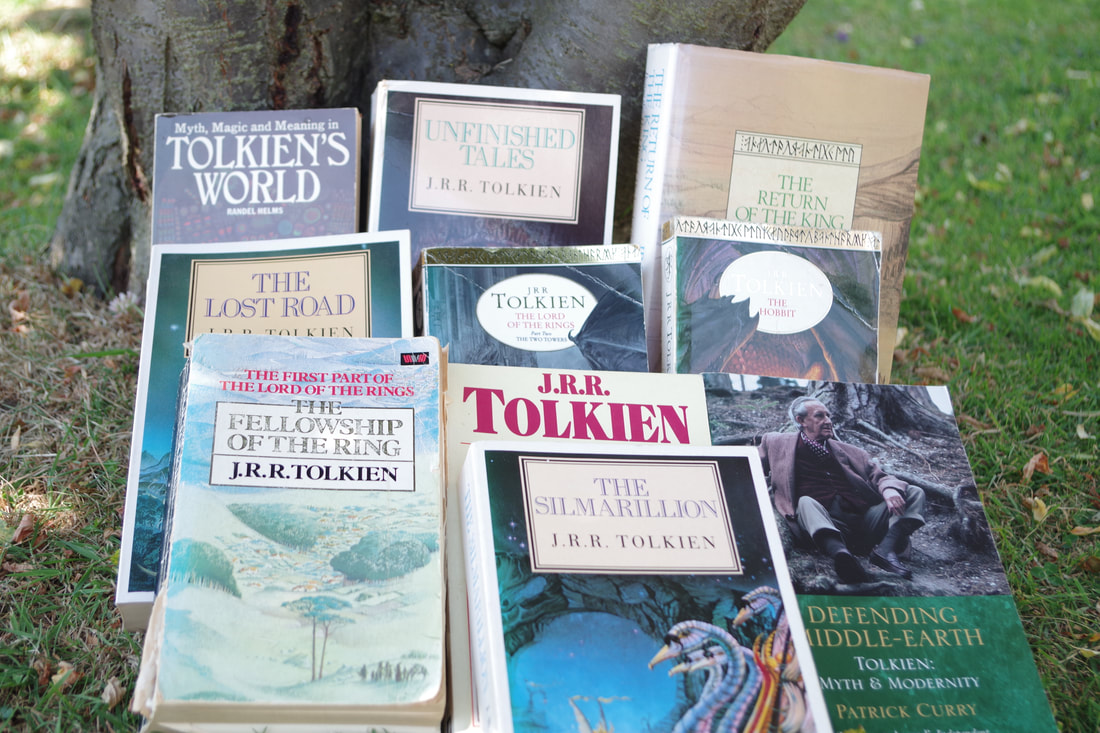

In this blog series, I am going to focus on four artists who have been particularly important to me and my creative work: Ian Miller, Elisabeth Frink, Paul Nash and Alfred Wallis. In this post, I am going to discuss the work of British fantasy artist Ian Miller. Since childhood I have loved the books of J.R.R. Tolkien, and my first encounter with the artwork of Ian Miller was in the book A Tolkien Bestiary; many beautiful and atmospheric images filled the pages of this book, but for me Miller’s illustrations stood out.

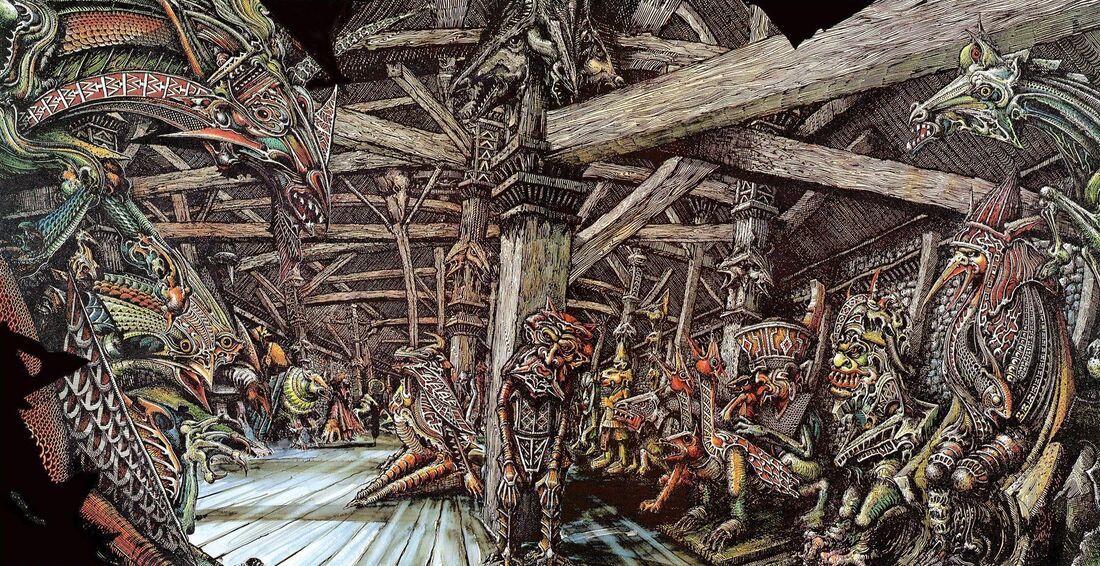

Whenever we read a novel we have our internal interpretations of the story, the setting and the characters, and I found in Miller’s images the darkness and intensity I’d always enjoyed in Tolkien’s books. For example, his portrayal of Helm’s Deep conveyed the terrifying scale of the battle, especially the monstrous, remorseless power of Saruman’s army – the whole image is so alive, I felt as though I could hear the battle, the clashing of steel, the drums, the screams. As with all Miller’s work, it boasts incredible detail, bursting with energy, two of the malevolent characters almost staring at, challenging, the viewer. When writing my epic fantasy Tree of Life trilogy, I wrote several battle scenes and I always keep this image of Helm’s Deep in my mind when doing so.

Born in 1946 and educated at St Martin’s School of Art, Ian Miller became one of Britain’s foremost fantasy illustrators. Known for his distinctive Gothic style, Miller’s work is immediately recognisable, and although profoundly original, I detect hints of Hieronymus Bosch, Pieter Bruegel the Elder and Albrecht Dürer in his work. Miller has worked on many book covers, including editions of H.P. Lovecraft’s stories and the Fighting Fantasy gamebooks. He contributed to Ralph Bakshi’s animated films, most notably the memorable post-apocalyptic science fantasy Wizards, where his macabre, richly detailed backgrounds added real atmosphere and a sense of depth.

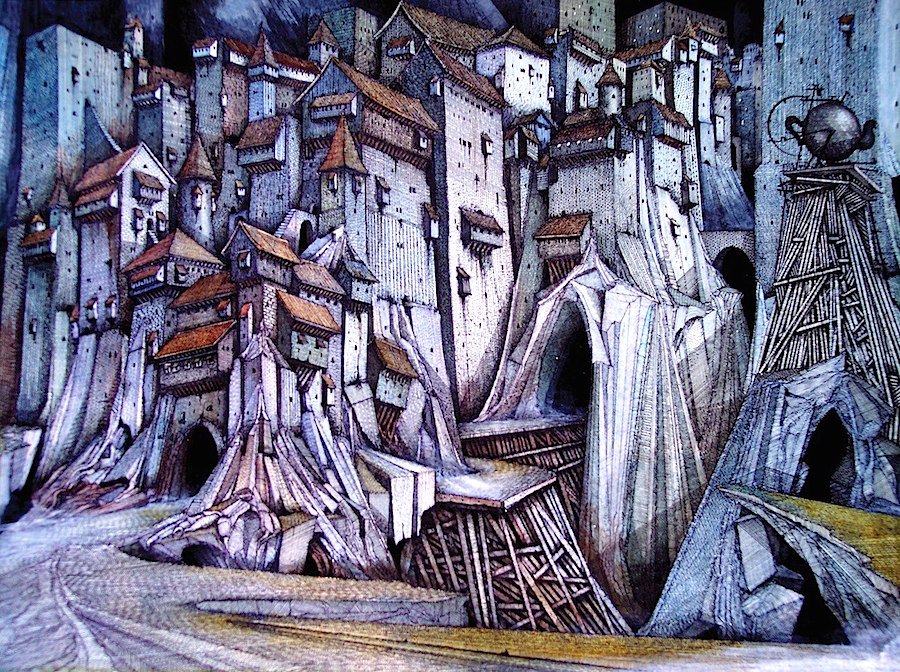

Miller also produced memorable illustrations inspired by Mervyn Peake’s classic series of Gormenghast books. Central to the story is the monstrous edifice of Gormenghast itself, whose ancient towers and mighty walls provide the ideal setting for the ritual-ridden people living there. Many of the characters inhabit the dank, damp corridors and rooms like ghosts, and the castle seems to be rotting and sinking. Through his dark, almost surreal style, Miller captures the slow decay of Gormenghast, hinting at the rising madness of the society within.

Miller once said:

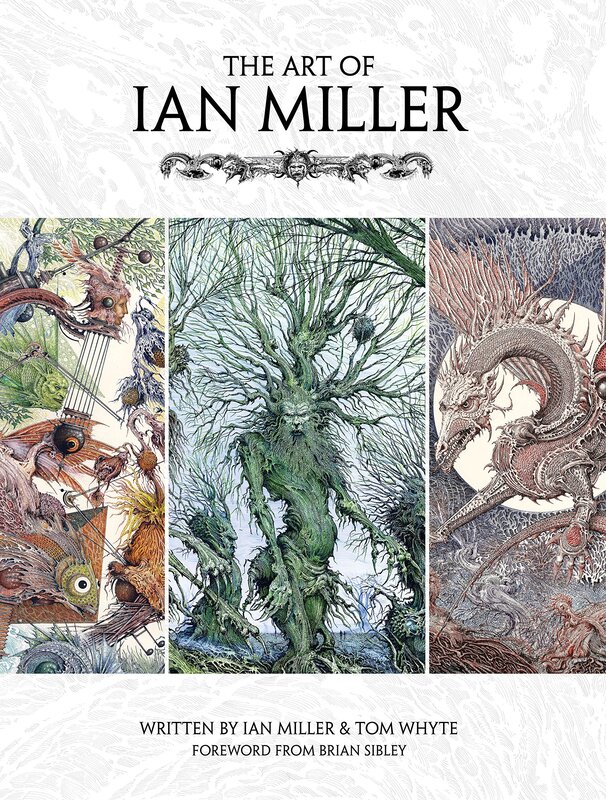

“Rust, falling facades, tottering buttresses, and an overriding sense of impermanence, these are the things which fascinate me the most.” These objects of fascination coalesce in Miller’s Gormenghast illustrations, creating frightening but compelling visions that truly complement Peake’s Gothic masterpiece. The bold, often grotesque and nightmarish visions of Ian Miller lurk always somewhere in my imagination; whenever I write scenes set in forests full of gnarled trees or in crumbling buildings and edifices, I know they are in part inspired by Miller’s work. If you are interested in finding out more about Ian Miller, there is a collection of his artwork in the book ‘The Art of Ian Miller’, which showcases the sheer scale and depth of his creativity.

If you’re interested in my writing, you can get the ebook version of my first novel - The Map of the Known World – for FREE. Please see the following Kindle preview:

1 Comment

Writing a novel is a demanding exercise: it requires imagination, focus, and the stamina and enthusiasm to keep working over a long period. Moments of frustration, drudgery and disappointment are, unfortunately, all part of the process, but there is an even more difficult challenge to overcome – self-doubt. Self-doubt is the voice that whispers: ‘your writing is not good enough – you’re not good enough.’ It can slow your progress, even sinking you towards writer’s block (which I’ve posted about previously). To date, I’ve written four novels (and am drawing close to completion of a fifth) and numerous short stories; I’ve attended writing courses and have read many books on the subject; I’ve also advised and supported other writers on their writing and publication journeys. Despite this, I regularly feel a weighty amount of self-doubt when it comes to writing. The following is a selection of the doubts I often feel… These characters are flat. The story makes no sense. Nobody is ever going to want to read this. I’ve run out of ideas. And there are many, many more… At its worst, self-doubt stifles my creativity, making me hesitate rather than taking positive steps forward.

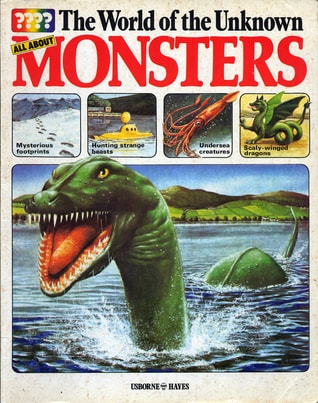

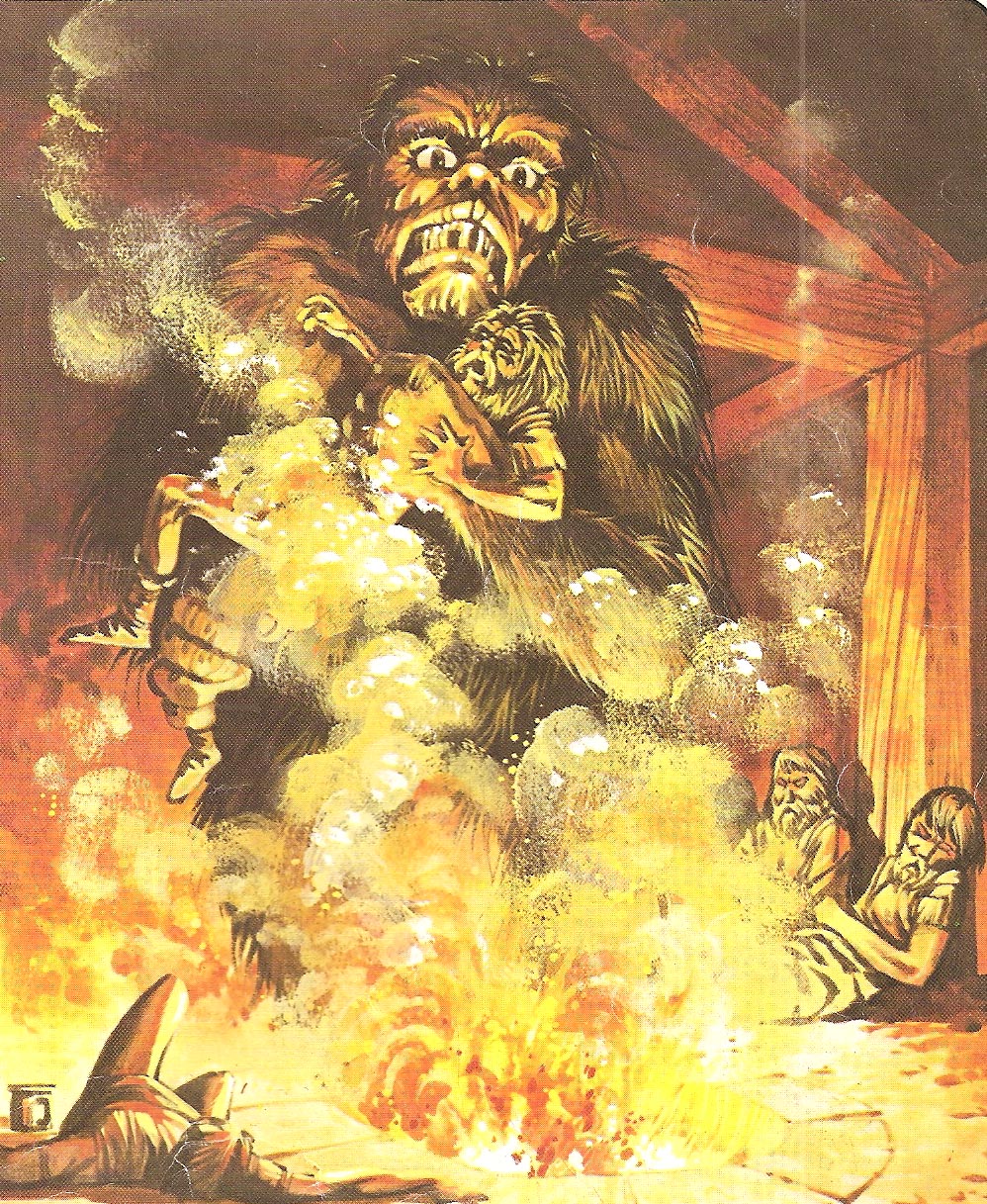

So, how can you overcome self-doubt? I’m not sure you can completely overcome it, but you can deal with it, and make sure it doesn’t stop you writing. Here are three tips: Manage your expectations: One advantage of self-doubt is that it challenges complacency: as a writer, it is healthy to have the ambition to keep improving your skills. However, there is a difference between ambition and expectation; the former is a positive, vital approach, the latter is a burden. An expectation can say ‘my writing must always be great’ - this sounds fair enough at face value, but dig a little deeper: is it reasonable to expect your writing to always be great? Of course it isn’t, but if you somehow believe this, then what is the inevitable outcome if your writing falls below par? You’ll feel like you are wasting your time, and that your work is worthless. This will only add further fuel to your inner self-critic, and this critic will do everything to convince you to stop writing. Cut yourself free from expectations – instead, just focus on trying to get better, trying to improve. Keep reading: Yes, it is tempting to compare yourself to other authors and when you read their books, their work will seem so polished, so impressive. But remember: their books have been fully developed, edited, proof-read – don’t compare them to your work in progress. So, keep reading as many books as possible – keep reading for inspiration and to learn more about different writing styles. Just keep going: When you’re hit by self-doubt, when your inner critic is at its most vocal, it is easy – and understandable – just to stop writing. But the best way to fight your self-doubt is to keep writing. Even if you’re writing badly, it is much better than not writing at all – if you stop writing, then your inner critic has won, and that can’t be right! Just write something, anything and see what happens. Don’t overthink your writing and never look for perfection. Just write for the joy of writing and you’ll create something, however small, that is worthwhile and this increase both your confidence and enjoyment. And if you keep going, I promise you the self-doubt will pass - it will come back, of course, but take advantage of the times when you’re feeling more confident, and use these to help keep going through the tougher moments. How do you try to overcome self-doubt as a writer? Add a comment and join the conversation. I’ve always loved monsters. Scary or friendly, gigantic or tiny, ugly or beautiful, it doesn't matter - somehow monsters help make sense of the world. As a child, books such as The World of the Unknown: Monsters (a great primer for any child interested in monsters) and Mysteries, Monsters and Untold Secrets fed my fascination with supernatural and mythological creatures, a fascination that has stayed with me into adulthood. Monsters are a consistent element in my novels: the Tree of Life trilogy is peopled by a cast of monstrous beasts such as the giant Carnifex, the winged Kongamato and the dreaded Malign Sleeper, not to mention the Redeemers who haunt Elowen from the very start of the story. Likewise, dragons, the ogre-like Thyrs and the demon-dog Barghests threaten the heroes of my novel This Sacred Isle. Monsters appear in the stories of every culture on Earth – we have been plagued by werewolves, centaurs, trolls, ogres, sea monsters and many more. They can manifest our deepest fears –or our deepest wishes; who has not longed to see a fiery dragon racing across the sky? In many mythologies monsters symbolised functions and aspects of humanity or the natural world. Monsters filled unexplored lands – as humans looked at blank spaces on their maps, of the lands beyond their borders, their imaginations created a fantastical menagerie. For example, in medieval times travellers’ tales spoke of dog-headed men and creatures with neither neck nor head, but with a face set into the middle of their chests. There were Amazons, satyrs, mermaids, Manticores – all portrayed in medieval art and literature. The tradition portraying monsters in art continued – some powerful examples include Apollo and Python by J.M.W Turner, The Colossus by Francisco de Goya and the myriad of beings in The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch. And this has continued into our own times, with monsters regular features of our books, films, television and games. Monsters might frighten, amuse or entertain, but they remain a constant feature of our imaginations. In this post, I want to discuss three of my favourite monsters. Of course, choosing just three is very difficult but if I tried to write about all my favourite monsters, this post would be endless! Some honourable mentions must go to Dracula, Medusa, the Minotaur and of course Talos (the giant bronze automaton so brilliantly created for the film Jason and the Argonauts). Balrog - from The Lord of the Rings I’ve posted before about the influence J.R.R Tolkien has had upon my writing and how reading the Lord of the Rings for the first time had an enormous impact on me. Many strange beings – good and evil – populate Middle-earth, and one that always intrigued me most was the Balrog, who attacks the fellowship in the Mines of Moria in one of the most memorable scenes in the whole book. In the complex mythology of Middle-earth, Balrog were once Maia spirits who were corrupted by Melkor / Morgoth into his evil service. The Balrog who appears in The Fellowship of the Ring was buried deep underground, unearthed accidentally by the dwarves to haunt the dark halls of Khazad-dûm. Tolkien does not rush to reveal this terrible being – its presence is hinted long before its appearance. First the fellowship hears troubling sounds" ‘That was the sound of a hammer, or I have never heard one,’ said Gimli. ‘Yes,’ said Gandalf, ‘and I do not like it. It may have nothing to do with Peregrin’s foolish stone; but probably something has been disturbed that would have been better left quiet.’ And after their initial struggle with the Moria Orcs, Gandalf says: ‘Something dark as a cloud was blocking out all the light inside.’ All this tension would be wasted if the monster failed to match our fears, but here Tolkien succeeds. When the Balrog is finally seen, we truly see its strength, its horror. ‘Its streaming mane kindled, and blazed behind it. In its right hand was a blade like a stabbing tongue of fire; in its left it held a whip of many thongs.’ Tolkien tells us enough to inspire fear and awe, but leaves space for the reader to imagine the gruesome details of the Balrog – everyone who reads the Lord of the Rings is left with their own impression of this monster of fire and darkness. I feel it was telling that in the run-up of the release of Peter Jackson’s superb film adaptation of The Fellowship of the Ring, the appearance of the Balrog was one of the most discussed elements – fortunately, Jackson’s version did not disappoint (the heat haze when the Balrog roared was a stroke of genius), and was an undoubted highlight of the film, adding yet more awe and horror to Tolkien’s monstrous creation. Grendel from Beowulf Grendel appears in the great Anglo-Saxon epic poem Beowulf. Composed sometime between 680 and 800AD, it tells of the adventures of the Scandinavian hero Beowulf as he battles three terrifying supernatural enemies: the monster Grendel, Grendel’s mother and a mighty dragon. Beowulf comes to the aid of Hrothgar, King of the Skyldings in Denmark. Hrothgar’s great hall Heorot has been abandoned for twelve years, following attacks by the monster Grendel, who strikes at night, crushing warriors to pieces and dragging their corpses back to the marshy wilderness. Grendel is provoked by the sounds of feasting from Heorot: “Then the brutish demon who lived in darkness impatiently endured a time of frustration: day after day he heard the din of merry-making inside the hall, and the sound of the harp and the bard’s clear song.” Beowulf confronts Grendel, tearing off the monster’s right arm in a furious struggle – the mortally wounded Grendel flees, returning to his marshy home to die. After Beowulf faces and slays Grendel's avenging mother, he becomes King of the Geats and reigns for fifty years, until he dies defeating a dragon that ravages his kingdom. My first awareness of Grendel came as a child when reading The World of the Unknown: Monsters and I saw a vivid depiction of him – his anger, his rage, his madness. I first read Beowulf at school and have read different versions since – including Seamus Heaney’s wonderful translation – and always find new pleasure and meaning in the story. My novel This Sacred Isle was in no small part inspired by Beowulf and the hero’s battles with the three monsters, and I am sure there are countless interpretations of what the character of Grendel means, but for me, Grendel symbolises fear of the unknown, of the wild, one of the most primal of all human fears. We live in an increasingly urbanised and connected world, but the fear lingers that in the remaining wild spaces, monstrous horrors still lurk… The Pale Man from Pan's Labyrinth The Pale Man is a haunting, unsettling presence in Guillermo del Toro's masterpiece of fantasy cinema: Pan’s Labyrinth. The story takes place in Spain during the early Francoist period, five years after the bloody Spanish Civil War. Ofelia travels with her pregnant mother to live with her stepfather, Captain Vidal, who mercilessly hunts the Spanish Maquis who fight against the Francoist regime in the region. The narrative intertwines the brutal reality with a mythical underworld - Ofelia meets a faun who tells her she is the reincarnation of a lost princess of the underworld realm; the faun gives Ofelia a book and tells her she must complete three tasks to acquire immortality and return to her kingdom. During her second task, Ofelia encounters the Pale Man: a child-eating monster, he is a hideous, cadaverous figure with eyeballs in the palms of his hands. He sits alone and motionless at a lavish banquet, though the plates and bowls of food are untouched. Although Ofelia is warned not to eat anything there, she takes grapes, awakening the Pale Man. He chases Ofelia, but she manages – just - to escape his murderous clutches.

The cruelty of fascist Captain Vidal, the Francoist state and a complicit Catholic Church are all embodied within the Pale Man: like these oppressive powers, the Pale Man devours the young, endlessly, piteously, a nightmarish vision of madness and lust. Monsters often reflect our worst human excesses, and in doing so form a warning we would do well to heed. I believe the Pale Man is fascism stripped of all pretence and illusion, stripped of all the flags, the uniforms, the speeches, the propaganda – all that remains is cruelty and monstrosity. Which are your favourite monsters? Please leave a comment and join the conversation.

One of the joys of reading fantasy fiction is the opportunity to dive into and explore imaginary worlds. Well-crafted secondary worlds are not mere background – they enhance and enrich the story, and help shape the characters and themes. These worlds feel like living and breathing places, as if the author is using a real setting, describing lands and places they have actually visited. Such worlds seem to exist beyond the immediate narrative of the story; as a reader you can easily imagine other stories happening simultaneously, with other characters experiencing adventures and challenges of their own.

In this post I am going to discuss three of my favourite imaginary worlds – Middle-earth, Osten Ard and Gormenghast. Middle-earth I have posted previously about how the work of J.R.R Tolkien inspires my writing, and of all the secondary worlds in fantasy fiction, Middle-earth is the most famous and the most imitated, inspiring settings across the genre of epic fantasy. Tolkien described his world: “The theatre of my tale is this earth, the one in which we now live, but the historical period is imaginary. The action of the story takes place in the North-west of Middle-earth, equivalent in latitude to the coastline of Europe and the north shore of the Mediterranean.” Middle-earth is complex and coherent, drawn from deep pools of mythology, language, history and geography. Tolkien’s academic grounding in Anglo-Saxon, Celtic and Norse mythology helped shaped the landscape. The scale and depth of Tolkien’s creation is almost overwhelming: the characters, races, lands and legends. Readers have long pored over maps of Middle-earth, exploring places such as the peaceful, bucolic Shire, Rivendell, Gondor, Mirkwood and the bleak, desolate Mordor.

This is an ancient landscape, with a real sense of history; Middle-earth shows the effects of time, with the remnants of lost civilisations such as the Tower of Amon Sûl, the Barrow-downs and the Argonath. The natural world is always present – flora and fauna, the passing of the seasons, the night-sky, the sun and the moon. Despite the fantasy elements – the creatures, the sorcery – Middle-earth feels real and the characters endure real physical ordeals (hunger, thirst and exhaustion); the rules of nature are not ignored, and indeed serve to underpin and strengthen the fantastical parts of the story.

The story is deeply rooted in the landscape: Middle-earth is alive, an active character in Tolkien’s work. For example, when the Fellowship attempts the pass of Caradhras, they describe the mountain as though it was a character: Gimli looked up and shook his head. ‘Caradhras has not forgiven us,’ he said. ‘He has more snow yet to fling at us, if we go on. The sooner we go back and down the better.’ And think of the forests of Middle-earth, such as Fangorn, Mirkwood and the Old Forest – these are not generic woodlands but places with unique characteristics, and perils, of their own, and each serves to challenge the characters in Tolkien’s stories. This is not an inert landscape, just a passive resource to be plundered – Middle-earth reflects Tolkien’s profound ecological concerns and his respect, even reverence, for the natural world. And Middle-earth is a threatened world, whether through the malice of Sauron or from Saruman’s uncontrollable lust for technology and power. The words of Saruman retain a chilling resonance to our own world’s problems: "We can bide our time, we can keep our thoughts in our hearts, deploring maybe evils done by the way, but approving the high and ultimate purpose: Knowledge, Rule, Order; all the things that we have so far striven in vain to accomplish, hindered rather than helped by our weak or idle friends. There need not be, there would not be, any real change in our designs, only in our means." Saruman ruins his environment to serve his own purpose – he is indifferent to the damage he creates, he sees only his own needs and desires. In our world of growing man-made environmental catastrophe, this is something we can easily recognise. Tolkien’s work may have a reputation at times for being cosy and inward-looking, but he warns against the folly of unfettered greed and ambition, and shows that exploitation of our natural world can lead only to our own suffering, even destruction. Middle–earth forms part of the imaginative landscape of millions of readers, and continues to be an inspiration for writers, artists, filmmakers, musicians and environmentalists.

Osten Ard

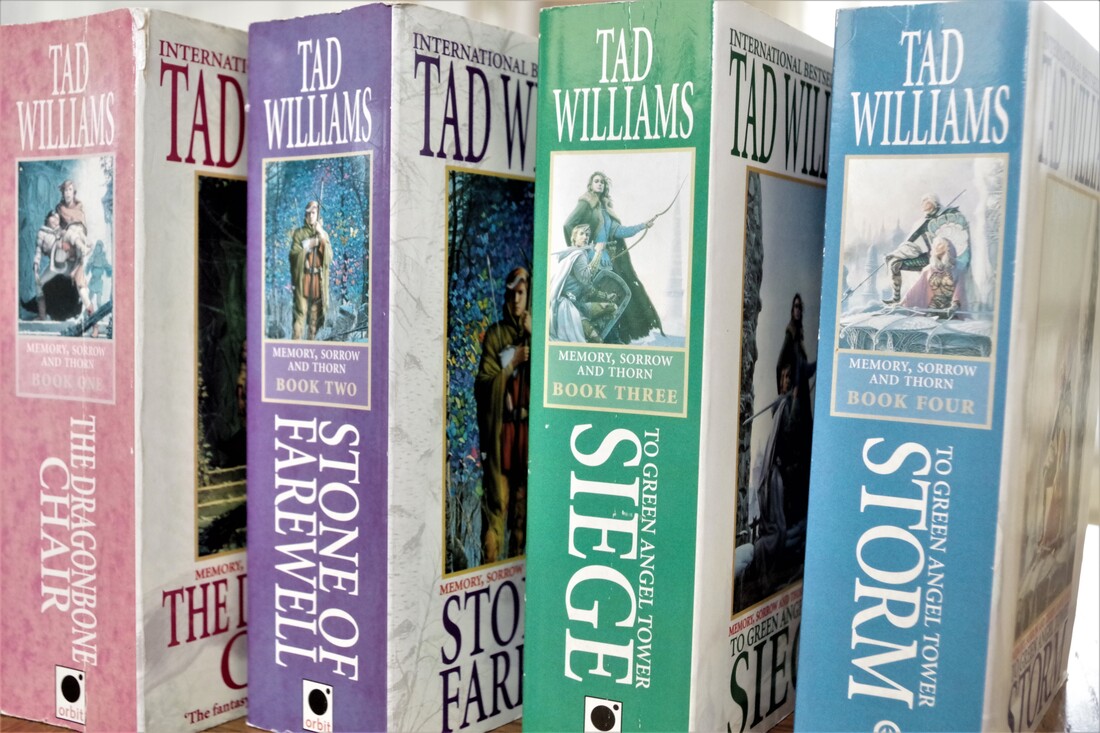

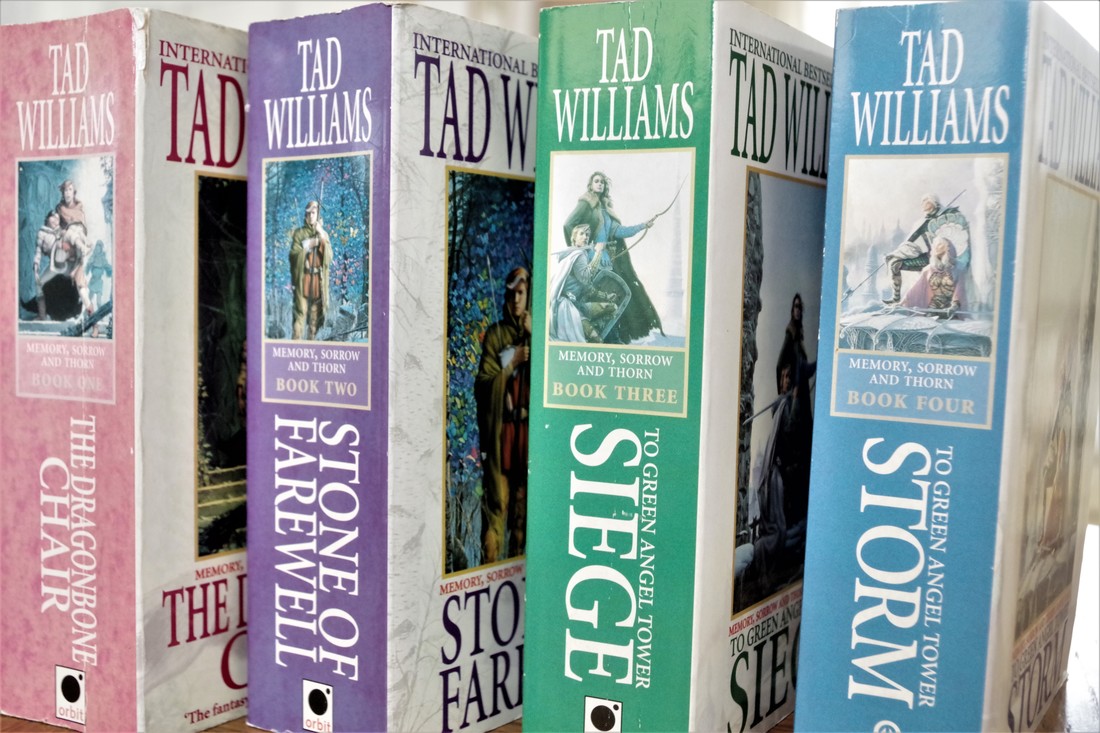

“Welcome stranger. The paths are treacherous today.” I first encountered the world of Osten Ard in Tad Williams’s landmark epic fantasy series Memory, Sorrow and Thorn – an influential work described by Locus magazine as ‘The fantasy equivalent of War and Peace.’ Superficially, Osten Ard resembles many Tolkien-inspired secondary worlds, with its medieval milieu, mountains, forests and swamps, but the Memory, Sorrow and Thorn series both uses and challenges many tropes and assumptions of the genre. There are few easy answers in Osten Ard, and do not expect simple separation into good and evil.

Memory, Sorrow and Thorn is a long read but never dry; written with wit, wisdom and intelligence, it is filled with excitement and memorable three-dimensional characters (Isgrimnur and Binabik are two of my favourites). And the world of Osten Ard – from the Wran to the Nornfells – plays an enormous role in the success of the story.

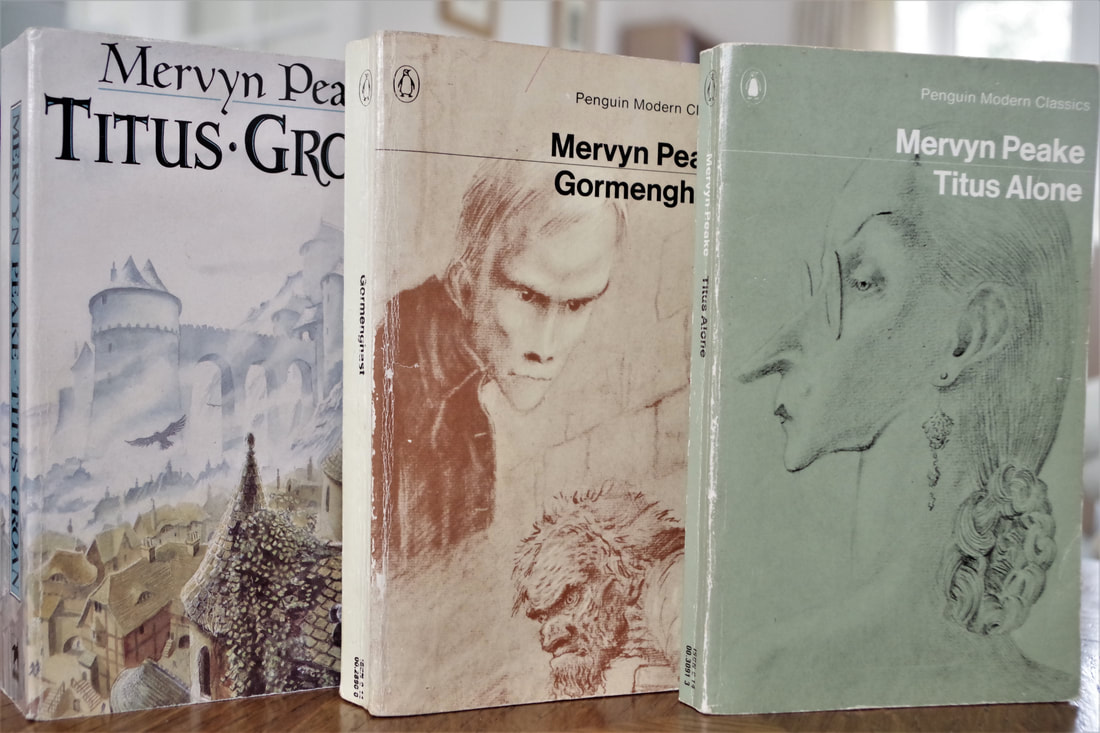

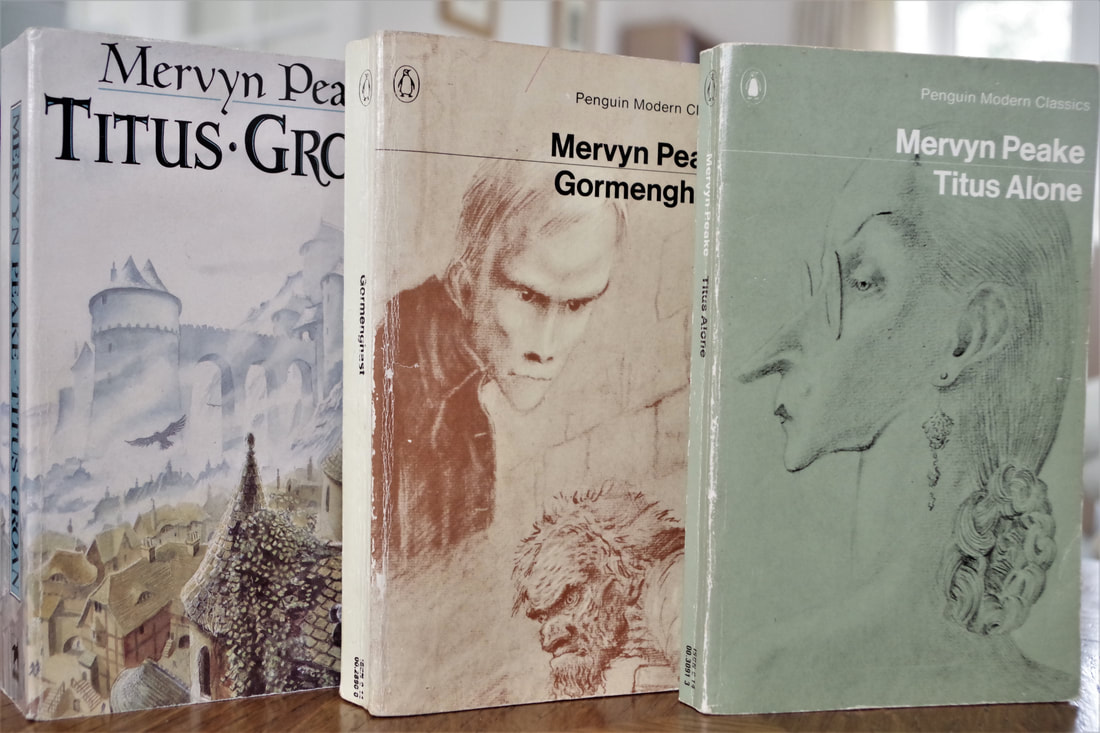

The depth and coherence of Osten Ard gives a strong foundation to the fantastical parts of the story, and in many cases reflects the psychology of the races and characters within. For me, the most fascinating part of Osten Ard is the fortress of the Hayholt. Doctor Morgenes describes it thus: “The Hayholt and its predecessors – the older citadels that lie buried beneath us – have stood here since the memories of mankind.” The Hayholt was formerly known as Asu'a, and was a city of the Sithi, the elf-like former rulers of Osten Ard, before it was besieged and captured by human invaders. The Hayholt is a haunted place, a place of secrets, with tunnels and caves beneath – it is not just a striking location, it symbolises suppressed human guilt over their genocidal war against the Sithi. This is typical of the complexity and ambiguity that lifts Osten Ard far above most secondary worlds in the genre. If you are yet to discover Memory, Sorrow and Thorn, then I recommend you make it your next fantasy read – the paths might be treacherous, but once you start exploring Osten Ard, you’ll find it a rewarding and absorbing journey. Gormenghast “Gormenghast, that is, the main massing of the original stone, taken by itself would have displayed a certain ponderous architectural quality were it possible to have ignored the circumstances of those mean dwellings that swarmed like an epidemic around its outer walls.” Sometimes lazily compared to the Lord of the Rings, Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast books (consisting of Titus Groan, Gormenghast and Titus Alone) resist easy description and classification: a fantasy, a scathing allegory of British life and society, a dystopian vision - whether the books are perhaps all these things or none, there can be no doubt they form a highly original work, dreamlike, layered and gothic. Central to the story is the monstrous edifice of Gormenghast itself; the ancient towers and mighty walls create a dense oppressive atmosphere, and an ideal setting for the madness of the ritual-ridden society trapped within. In less skilful hands, the dark architecture – the Stone Lanes, the Tower of Flints, the Great Kitchen – could have submerged the story, but instead through Peake’s witty prose, the setting adds elements both surreal and darkly comic.

The story is peopled by a carnival of eccentrics, such as the demonic cook Swelter, the cadaverous Mr Flay, Lord Sepulchrave (76th Earl of Groan), morose, exhausted, depressed by the endless demands of his role, and of course the murderous kitchen-boy Steerpike, the main driver of the narrative who schemes and slaughters his way to power. With life orchestrated by each day’s instructions from the Book of Ritual, many of the characters inhabit the dank, damp corridors and rooms of Gormenghast like ghosts. Yet, although the inhabitants of Gormenghast are larger than life, they have only too human foibles and failings such as greed, vanity and ambition. It is a fantasy but one uncomfortably close to our own lives; if we choose to look we can see our own weaknesses reflected.

Despite the eccentricities (though this is not a fantasy world of magic and dragons), Gormenghast feels so real, so tangible. When reading these books, I can almost smell the damp and mould, shiver in the cold rooms and passages, cower under the crumbling walls and towers of stone. Gormenghast itself, huge and malevolent, seems to be rotting, sinking, reflecting the corruption and empty ritual of its society. But while there is doubtless darkness in the Gormenghast books, a deep, suffocating darkness at times, one can also find kindness, humour, beauty and tragedy, all held together by Peake’s wit, psychological insight and vision. Which are your favourite fantasy worlds? Please leave a comment and join the conversation. If you’re interested in my writing, you can get the ebook version of my first novel - The Map of the Known World – for FREE. Please see the following Kindle preview: The Tripods first strode into my consciousness with the 1984 BBC TV adaptation. Once I’d seen the stirring, ominous opening credits and the first glimpse of the marching mechanical monsters, I was hooked, and the series became a regular Saturday teatime treat. It was unlike any show I’d seen before – the special effects were impressive for the time, especially for television. Sadly, the BBC decided the viewing figures did not justify the high costs of the series and so the final volume of the trilogy was never produced; a rushed, bleak ending was tacked to the last episode of series two. However, the story and the world of The Tripods fascinated me and so I simply had to read the books, and I was not disappointed. The Tripods, written by John Christopher (Sam Youd), is set in a future where Earth has been conquered and humanity enslaved by the alien Masters ,who bestride the world in the Tripods, enormous three-legged walking – and when needed, fighting - machines. Human society has returned to a pastoral, pre-industrial level, with few towns – obedience to the alien rulers is established through Caps, compulsory implants every human receives at the age of fourteen. Once the Cap is implanted, humans become docile and lose any sense of curiosity and rebelliousness. The main hero of the book is thirteen year-old Will, an English boy, who is suspicious and fearful of the Tripods. With his ‘Capping Day’ approaching, Will flees with his cousin, Henry, to the ‘White Mountains’ in Switzerland, the refuge of the Free Men. During their dangerous journey across France, they meet up with another boy, Jean-Paul, quickly nicknamed Beanpole. Beanpole is clever and inventive, and fears that Capping will steal his curiosity, and so he joins Will and Henry on their quest for freedom. During their subsequent adventures, they face danger not only from the Tripods (and the alien Masters who control the machines) but also from Capped adults. When I came to write my own books, it is clear The Tripods influenced my work. For example, there are elements of my first novel, The Map of the Known World, clearly shaped in part by Christopher’s trilogy, from the theme of defying orthodoxy and dogma, to key plot points, such as young people escaping a tyrannical society and seeking refuge in distant mountains, and the Null that breaks free will and enforces obedience. The Map of the Known World is a fantasy novel, not science fiction, but I freely acknowledge my debt to Christopher’s creation. Reading The Tripods as a child I was drawn into the exciting story of aliens and adventure, especially moments such as the eerie journey through a ruined Paris and the mission to the Masters’ city. But beyond the power of a good story effectively told, the key themes of The Tripods remain fascinating and resonant.

The world of The Tripods is a dystopia, but an unusual one, as its inhabitants are, on the whole, contented, or at least – thanks to the Cap – unable to contemplate the possibility of a different existence. Indeed, humans refer to the time before the coming of the Tripods as the Black Age. “There were too many people, and not enough food, so that people starved, and fought each other, and there were all kinds of sicknesses.” The White Mountains Capped humans never defy the Tripods, who they believe protect them from descending into the horrors of disease, famine and war. The world ruled by the Tripods is peaceful and humans live simple, untroubled lives; there are moments in The White Mountains (the first book in the trilogy), where Will is tempted to abandon his quest, for example, when he reaches Le Chateau de la Tour Rouge – he falls for Eloise, the daughter of the Comte and Comtesse, and feels the allure of a ‘secure and pleasant life’. Yes, Will and his friends are brave to undertake their dangerous journey to the White Mountains, but their true courage comes in defying the views and beliefs of family, friends, teachers and village elders. It is Will’s determination to oppose all the people with whom he has grown up that marks him as a hero in the making. He knows, or at the very least senses, the society in which he is living is rotten and unjust, and so seeks to escape. And as is clear from early in the story, the freedom offered by the Free Men is not easy: “To the south. To the White Mountains. With a hard life at the journey’s end. But a free one.” The White Mountains Freedom is the price of the security offered by the Tripods. The Cap neuters humans’ capacity for challenging thought, imagination and creativity, and dulls any desire for progress or further understanding of the world. It could be argued the political forces of our own age are often shaped by a desire to return to simpler times, to retreat from and turn our backs to the complexity of the modern world. In The Tripods, Christopher suggests people are happy to trade freedom for the safety and protection offered by the tyrannical rulers. Even as a young reader, The Tripods started me thinking about questions of freedom and of the importance of challenging authority, even when (especially when) it conflicts with the entrenched views of those around you. This is made clear early in The White Mountains when Will worries about his impending Capping Day: “Only lately, as one could begin to count the months remaining, had there been any doubts in my mind; and the doubts had been ill-formed and difficult to sustain the weight of adult assurance.” The White Mountains I would argue freedom, questioning authority and the desire to travel are all human rights, and in this book all are denied by the alien rulers. Christopher is, I believe, warning us we must be careful not to allow our own rulers to fool us into trading these precious rights for a feeling of safety from outsiders. As Julius, the leader of the Free Men says: “Free men may govern themselves in different ways. Living and working together, they must surrender some part of their freedom. The difference between us and the Capped is that we surrender it voluntarily, gladly, to a common cause, while their minds are enslaved to alien creatures who treat them as cattle. There is another difference, also. It is that, with free men, what is yielded is yielded for a time only. It is done by consent, not by force or trickery. And consent is something that can always be withdrawn.” The Pool of Fire And, without spoiling the ending, the trilogy finishes on a melancholy, unsentimental note, but one that feels true, for humanity is, sadly, quite capable of conflict and division without the intervention of aliens. As both a reader and an author, I continue to cherish The Tripods, and I hope new generations find both pleasure and meaning in the books. And, of course, if someone could produce a new adaptation, and this time adapt all three books, that would be good too… The influences that shape an author’s work can be varied – I’ve posted before about some key influences on my writing, such as the novels of J.R.R. Tolkien, Watership Down and many others. One area I’ve not mentioned previously is video games. I’ve enjoyed playing fantasy RPG games such as Dragon Age and the Elder Scrolls: Skyrim, but the era of gaming that left the greatest impression upon me was my childhood days on the Sinclair ZX Spectrum. I loved many Spectrum games – Sabre Wulf, Dun Darach and Where Time Stood Still were great favourites – but for me nothing matched The Lords of Midnight and its sequel Doomdark’s Revenge. The Lords of Midnight was originally released (published by Beyond Software) in 1984 for the ZX Spectrum. The player undertakes a quest to defeat the evil Doomdark, who has cursed the land of Midnight with an everlasting winter. The Lords of Midnight could be played like an RPG, where you seek to destroy the Ice Crown, the source of Doomdark’s power. Or, if you were feeling more war-like, you could recruit other lords and gather armies to face and defeat Doomdark in battle. The game’s creator, Mike Singleton, punched through the technical limitations of the ZX Spectrum to create a truly innovative piece of software. Singleton developed a bold technique he named landscaping to bring the world of Midnight to life by offering the player a first-person perspective. This technique provided an immersive experience, as the player moved through forests, mountains and past powerful stone fortresses. It was said the game contained 32,000 views of the landscape, a staggering programming achievement with only a scant 48K available. Singleton followed The Lords of Midnight with an equally strong sequel, Doomdark’s Revenge, which used a similar structure and game mechanics but was even larger in scale and complexity. Everything about The Lords of Midnight gripped me, from the superb packaging and cover art, to the memorable characters such as Luxor the Moonprince, Rorthron the Wise, and my favourite, Farflame the Dragonlord. The landscapes were simple but so atmospheric . The game’s day / night cycle created tension - I would nervously watch the text commentary during the night section, seeing the various battles listed, waiting for dawn to discover the fate of my characters. Night has fallen and the foul are abroad... How could a video game with no animation, no sound, no music, prove so absorbing, so memorable? First of all, The Lords of Midnight had a clever, well-worked story and an evocative, Tolkienesque setting. Crucially, the varied gameplay meant no two games were ever the same, drawing you back to play time after time. By today’s standards, The Lords of Midnight seems simplistic, but there is something about the game’s crisp, distinctive graphical style – it provides so much atmosphere and energy, you almost think you can hear the crunch of snow and ice beneath your feet, and the howling of hungry wolves. The Lords of Midnight somehow managed to meld the imaginations of the developer and the player – the game gives enough symbols and leaves enough space for the player to add in their own details, to imagine elements beyond those presented on screen. I am not surprised The Lords of Midnight has continued to inspire game designers and authors; there are numerous websites, emulations and now even an official novelisation, written by Drew Wagar, all drawing upon the rich tapestry of Singleton’s creation.

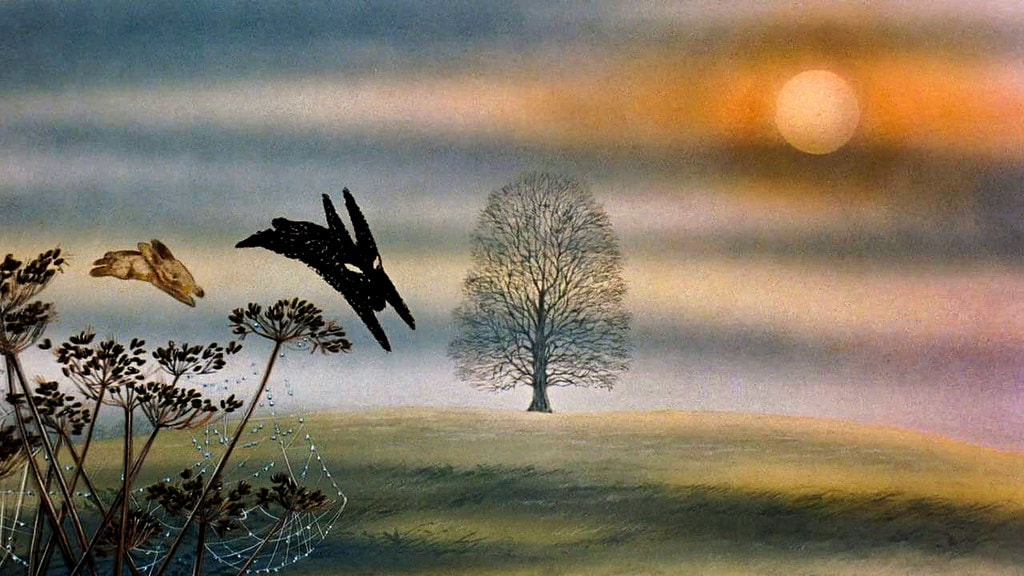

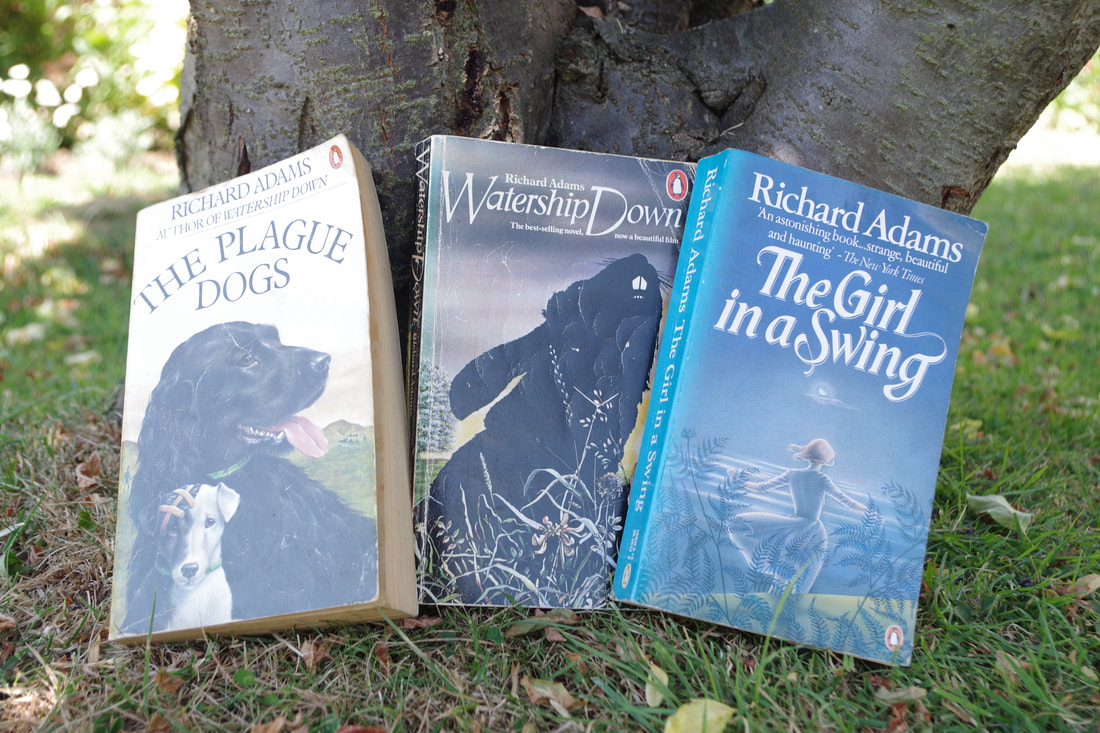

Elements of The Lords of Midnight have certainly appeared – unconsciously or otherwise - in my own writing. The cursed snow-bound realm of the Myrkvid in The Map of the Known World is influenced by the land of Midnight, and in This Sacred Isle, I am sure the dragon Athanor has echoes of Farflame the Dragonlord! I believe Mike Singleton quietly inspired many others in their creative endeavours, and that his work, especially in the icy lands of Midnight, will continue to influence and entertain for many years to come. There are some books that stay with you throughout your life, books you first read as a child that shape your interests, even your worldview. For me, one of those books is Watership Down by Richard Adams. My introduction to Watership Down was through Martin Rosen’s 1978 film version – my dad took me see it at the (long-closed) ABC cinema in Ipswich and although too young to fully understand the story, the visuals left an indelible mark. I didn’t find the (now much-discussed) violence of the film unsettling; I just thought it was magical and extremely exciting. When a little older I finally read the book and it was one of the reading experiences that one only seems to have in childhood – long hours reading, no distractions, no sense of the world outside. I soon discovered that as thrilling as the film had been, the novel contained a far deeper, darker and even more satisfying story. Although the story takes place across just a few miles of English countryside, it is an epic adventure, and I found myself lost in the saga, fascinated by characters such as Hazel, Fiver, Bigwig and the terrible General Woundwort. When I first started writing short stories and novels, Watership Down remained one of those touchstones I returned to for inspiration, for encouragement. Indeed, the Isle of Ictis scene in my first novel, The Map of the Known World, was heavily influenced (in atmosphere and – in many ways – narrative function) by the creepy, disturbing sequence in Cowslip’s warren. I have longed admired the richness of Adams’s descriptive writing – the landscape of Watership Down, described of course from a rabbit’s eye view, is beautifully evoked, from the colours and scents of flowers, to the sinister buildings and machines built by humans. This sense of the landscape being intrinsic to a story is something I have carried through all my work, and in my novels such as This Sacred Isle, I have consciously tried to evoke the land as almost a character in itself, a character that influences and responds to the events of the story. Watership Down is not a direct allegory such as Animal Farm (another favourite book of mine) but through its themes, it offers strong comments on our world. For example, when I re-read the book as an adult, Adams’s interest in justice, specifically just leadership became clear through is treatment of the four warrens we visit during the story. Sandleford Warren is hierarchical, entrenched in its own rules; its chief, although wise and experienced, has largely withdrawn from contact with the world around him, and thus ultimately fails to understand or appreciate the seriousness of the threat facing the warren. He fails to act, condemning all, with the exception of Hazel and his friends, to extermination. As we move through the story, we come to Cowslip’s warren, where the inhabitants have effectively been tamed, and depend on the food supplied by the farmer, though with the knowledge that their life or relative ease means that regularly one or more of their kind will be caught within the snares. They are strictly not a community – they live almost individual lives, resigned to their fate, caring little for others. General Woundwort’s warren, the dreaded Efrafa is even worse – a tyrannical warren, where fear rules and any disobedience is punished by wounding or death. Only when the final warren is established on Watership Down is a just leadership achieved; the community is led by one who has earned the right to lead, not through power or fear or deviousness, but by intelligence, compassion and selfless actions. Perhaps Adams is reminding us to choose our leaders carefully – a lesson we would do well to heed… Adams clearly also had a profound understanding and knowledge of mythology and folklore. He makes references to classical mythology and literature in the novel, and was influenced by Joseph Campbell’s Hero of a Thousand Faces. The tales of trickster El-ahrairah have an authenticity, a heft, as though they are truly stories passed down and shaped by countless generations, as powerful guides to society, to life and death. And these stories are not just added to Watership Down to add colour and texture; although entertaining tales in their own right, they are not just entertainment. The adventures of El-ahrairah inspire and influence decisions and actions taken by characters in the book. In many ways, I believe Watership Down is a story about the power of story, the necessity of story in our lives – El-ahrairah gives meaning to the rabbits, an identity, connecting them to their past and encapsulating shared experiences across their species. One of the elements that separates Hazel and his companions from Cowslip’s warren is the latter’s rejection of the tales of El-ahrairah, a rejection of what unites their kind, a rejection of the lessons and hardships of the past, and a focus solely on the present: ‘Well, we don’t tell the old stories very much,’ said Cowslip. ‘Our stories and poems are mostly about our own lives here…’ Adams asserts that we all need stories – religious or otherwise – to make sense of our existence and to understand and connect with others. The power of story gives strength, energy and hope to Hazel and his companions, even in the darkest times; this contrasts to the stasis and imprisonment of Cowslip’s warren, where they have cast aside their freedom for a life of relative ease, and care little for each other, as Cowslip says: ‘Rabbits need dignity and above all, the will to accept their fate.’ Hazel, Fiver, Bigwig and the other rabbits escaping from Sandleford Warren refuse to accept their fate – they know their journey places them in danger, appalling danger, and that their chances of success are slim, but they have learned, partly through the tales of El-ahrairah, that to have any chance of survival, they need to act, to use their wits and to work with each other as a community. The impact of humanity on the natural world forms one of the most powerful themes in the novel. Throughout the book, we see the damage caused by humans, often through sheer indifference:

‘It comes from men. All other elil do what they have to do and Frith moves them as he moves us. They live on the earth and they need food. Men will never rest till they’ve spoiled the earth and destroyed the animals.’ The location of Sandleford Warren is starkly described as ‘SIX ACRES OF EXCELLENT BUILDING LAND’, nature reduced to a commodity, a resource. The warren is not destroyed deliberately or even out of malice – the rabbits’ existence is simply an irrelevance, their lives deemed worthless against the needs of humans. This was something that clearly troubled Richard Adams, who valued the natural world and the rights of non-human species. And it is not difficult to see how the creeping danger and damage of urbanisation Adams attacked are being realised in the real world. The fields and meadows around the English village in which I live are gradually disappearing beneath concrete and brick, any ecological concerns brushed away – what has been lost can never be recovered. Our ecology is irrevocably damaged by such relentless ‘development’, and as I believe Adams felt, our society is damaged too. Watership Down asks us to notice the world around us, the world around our feet, to see the beauty, the complexity, the richness of animal and plant life – only by seeing, only by understanding, will we value the natural world enough to take steps to protect it. I am sure Watership Down inspired many people to draw, to compose music, to write (I count myself in the latter) but I wonder how many people it inspired – and still inspires – to become environmental campaigners, or work to support animal rights? Watership Down is a book that can help us view the world in a more balanced, compassionate way - it is testament to the strange, sheer power of story that a tale of a small group of rabbits travelling through the English countryside can teach us valuable lessons about our lives too.

Writing a novel is a long-term undertaking, measured by months and years. To keep your creativity fresh during that time is one of the toughest challenges writers face. I am deep in the process of revising my latest novel, Second Sun – I’m enjoying it, the book is taking shape, the characters and setting are beginning to gel but I cannot lie, it’s been tough going at times. That initial blast of writing the first draft, where everything seems new and the possibilities are endless, is replaced by the often repetitious slog of working and reworking the text, made harder of course by the other demands and responsibilities we all have in life.

I guess this is common to all writers. Books are not written in sudden explosive bursts of creativity, but in the steady, plodding effort of writing, revising and editing (not to mention planning and research). The progress can feel slow, painfully slow, almost as though you are not making progress at all. It is a different feeling from writer’s block (something I have blogged about previously), where it seems hard to form any new ideas, when even putting down a sentence becomes a monumental struggle. No, this is about keeping going, maintaining momentum, however much you feel like giving up.

I’ve always believed it is not the writing you do when you feel energised and inspired that counts – much more important is the work you do when you don’t feel like writing, the work you do when you’re tired or stressed, the work you do because you’re passionately committed to getting your book finished. Writing a novel is a tough task and there will be bumps in the road, however, this doesn’t mean there’s nothing you can do to make the process a little more comfortable and ultimately, more rewarding. Here are a few ways you can stay on track:

Distance When the going gets really tough, take a break, take a metaphorical step back from your work in progress. It’s not about giving up, but about giving yourself a chance to remember why you are writing, to remember what you are trying to say through your book. It’s ok to fall out of love with your book at times – it will happen, and you’ll forgive it eventually! Putting some distance between you and your book will allow you to see above the day-to-day slog of writing and rewriting. Curiosity No doubt you have done lots of research for your book but even though you are heavily into the process of writing it, it doesn’t mean you should stop learning and exploring. Stay curious - get out and about if you can; for example, I always find a trip to a museum or an art gallery inspires fresh ideas – failing that, reading reference books on related subjects, such as mythology, art and history can provide new insights and angles, which bring new life to your writing.

Break your routine

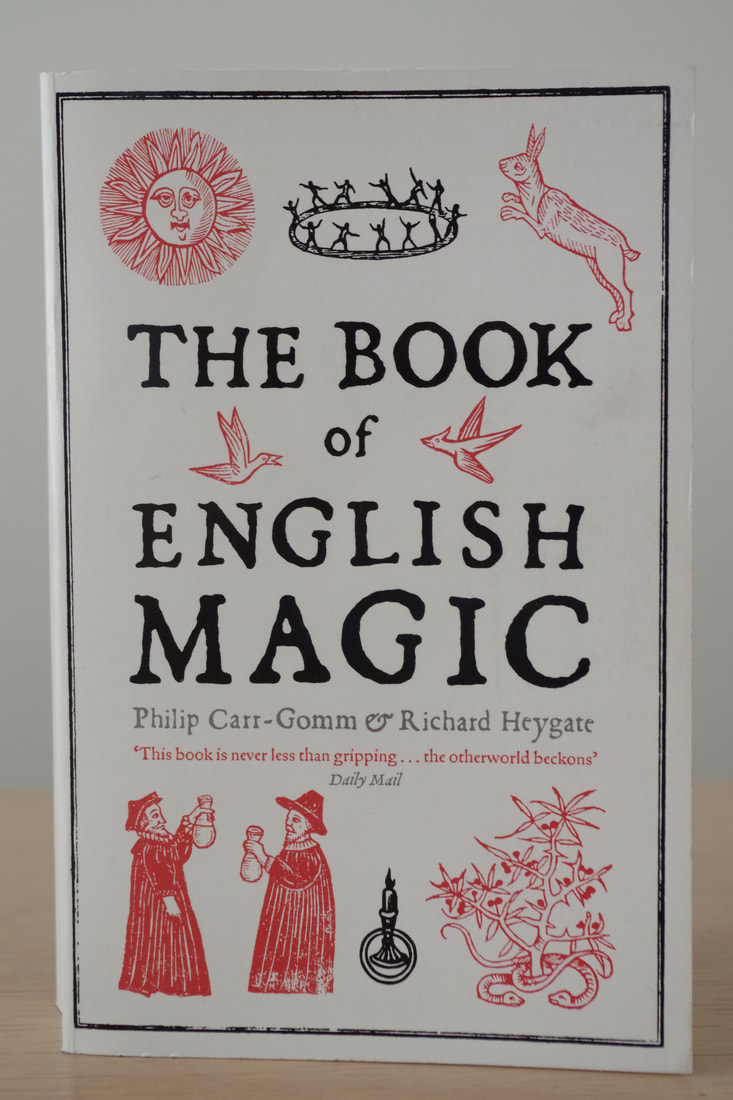

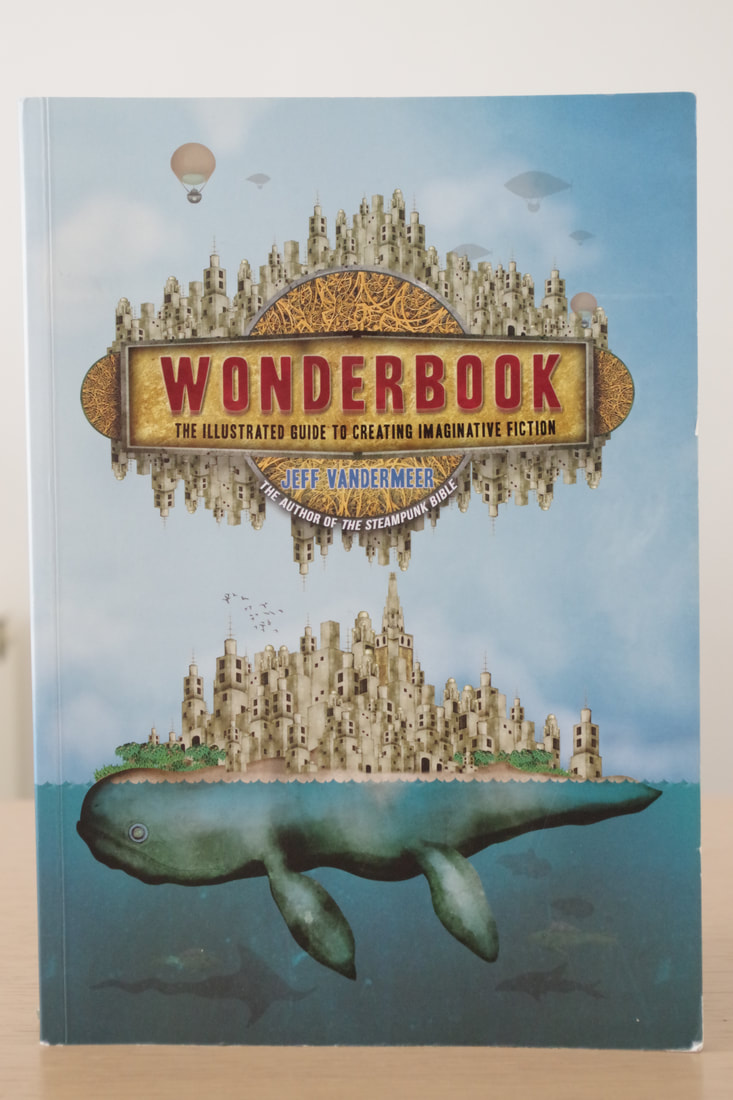

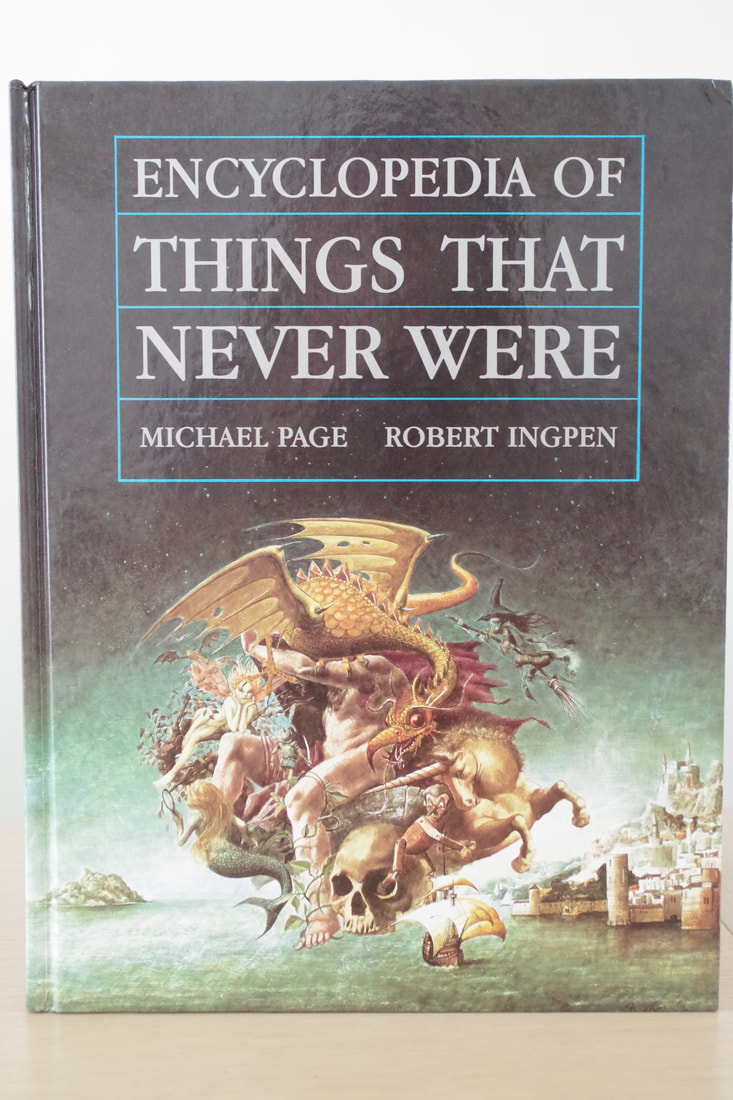

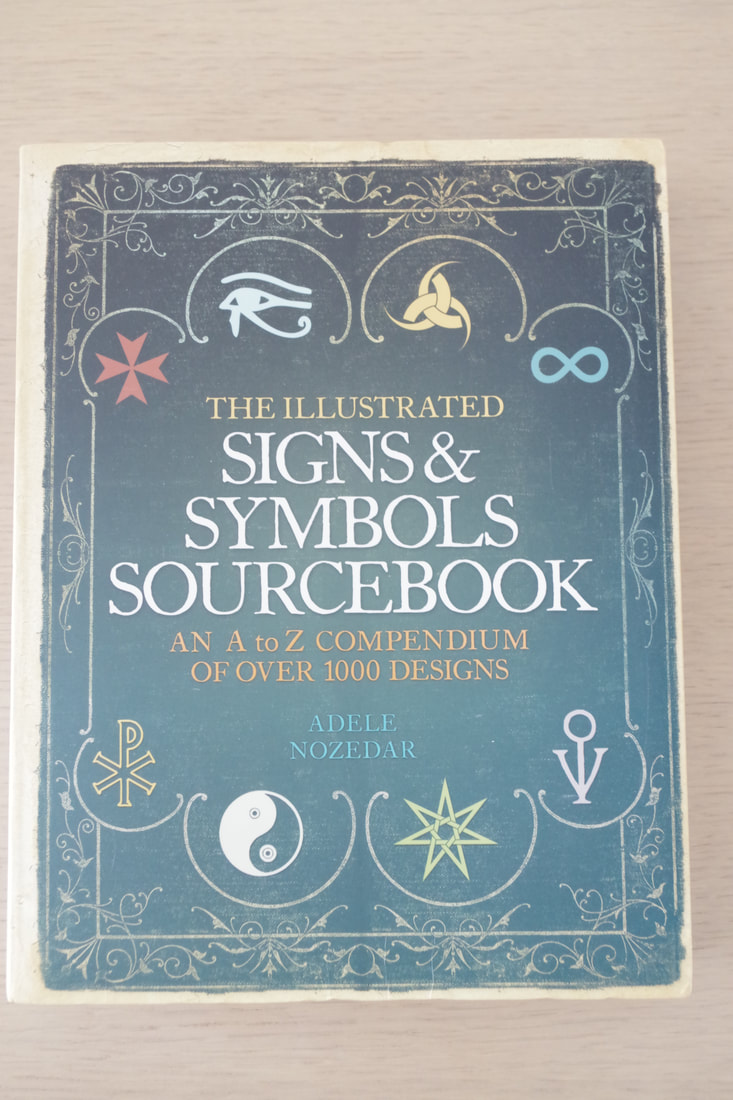

We all have writing routines and habits, and these are often very helpful. However, when progress slows and the process feels stale, it is worth trying to do things differently. Just try some simple changes: if you can, work from a different room, or write longhand for a while rather than using a computer – anything to disrupt your normal routine and help you look at your work with a different perspective. If you’re feeling more daring, perhaps even try one of Brian Eno’s oblique strategies, which are posted daily to his twitter account (https://twitter.com/dark_shark) Keep reading When you’re deep in the process of writing a novel – tired, anxious and frustrated - the idea of reading a book for pleasure can sometimes feel like adding insult to injury! But if you want to write, you must keep reading, even if it’s just for a few minutes each day. As well as the sheer enjoyment of reading, if you read a good variety of books it can only improve your writing – you will pick up, consciously or unconsciously, new ideas and techniques that will permeate your writing. I hope these are some useful pointers for when the going gets tough. Writing a book is a long journey, but word by word, sentence by sentence, you will get there! If you’re interested in my writing, you can get the ebook version of my first novel - The Map of the Known World – for FREE. Please see the Kindle preview below: Research is a key part of writing any novel and has always been something of a passion of mine. Whether it is researching the Anglo-Saxon world of 6th century England for my novel This Sacred Isle, or building an entire secondary world for my Tree of Life trilogy, I love digging down to establish key facts. Sometimes, this research takes the place of visiting actual historical sites or museums / galleries – often, though, my research is through non-fiction works (I am a regular customer at my local library!). Often, I will use non-fiction books to confirm important details about the world in which my story takes place – for example, for This Sacred Isle, although it contains elements of fantasy, I very much wanted the setting to have a strong historical basis, such as the food people eat, their clothes, their weapons etc. However, good non-fiction can also provide inspiration for elements I would never have thought of otherwise, taking the story in different directions. In this post, I am going to talk about four non-fiction books that I have found inspiring when writing my novels, non-fiction books to which I’m sure I’ll continue to return. The Book of English Magic - Richard Heygate & Philip Carr-Gomm This is a wonderful survey of England’s magical past, covering druids, Anglo-Saxon runes, Merlin, Alchemy, Freemasonry, and much, much more. Erudite but accessible, this hugely entertaining, enrichening book is a primer for occult history, and has opened for me many rich seams of research and inspiration. I returned to this book a number of times whilst writing This Sacred Isle, both for the sections on Anglo Saxon magic and the Matter of Britain, and also for the section on Alchemy and Tarot, which in their way influenced the shape of the story. The book contains short biographies of leading figures within magical history, such as Aleister Crowley, as well as focuses on writers inspired by England’s magical tradition such as J.R.R. Tolkien, Susanna Clarke, J.K. Rowling and Philip Pullman. There are suggestions for places to visit, and articles written by modern day magical practitioners, which I found fascinating and in places, very moving. Even if you don’t believe in magic, read The Book of English Magic with an open mind, and it will take you on a trip to the Otherworld… Wonderbook – Jeff VanderMeer Wonderbook has proven to be a valuable addition to my non-fiction collection. It is an illustrated creative writing book, aimed mainly (though not exclusively) at writers of the fantastical (all SF, Horror and Fantasy authors will find reams of good material to explore here). It is jam-packed with advice on plotting, structure, characterisation, world-building and many more aspects of fiction writing. I used this book during the edit of This Sacred Isle, and it helped me to see some different perspectives on my work, especially in terms of narrative design and testing my characters. The exercises and advice contained within Wonderbook made me challenge my work even more, to question my assumptions, to keep trying new techniques. The heavily visual, often playful and irreverent, approach is bold and innovative, and the book also contains articles / interviews with writers such as George R. R. Martin, Neil Gaiman and Ursula Le Guin. And it is not just the practical advice that makes Wonderbook such a valuable book for writers – it gives plenty of inspiration just to keep going, especially when the going gets tough. Encyclopaedia of things that never were - Michael F. Page and Robert Ingpen I picked up this book many years ago, and it’s been a faithful companion for my writing since then. It might be tricky to get a hold of a copy now, but it’s worth it if you can. Drawing on examples from myth, legend and fantastical literature from around the world, you’ll discover all manner of mystical places, people and creatures. Richly illustrated, it is an entertaining, witty read, and I used the book to spark ideas for my Tree of Life trilogy - the saga takes place in an invented secondary world, and the Encyclopaedia of things that never were sparked many ideas for the creatures that inhabited that world and lands in which they lived. For any lover of fantasy, I would recommend this book – leave logic at the door, and enter a world of dreams… The illustrated Signs and Symbols Sourcebook - Adele Nozedar This is a comprehensive and well-illustrated guide to the secret knowledge of signs and symbols, which I found both useful as a source for research and an entertaining read in its own right.

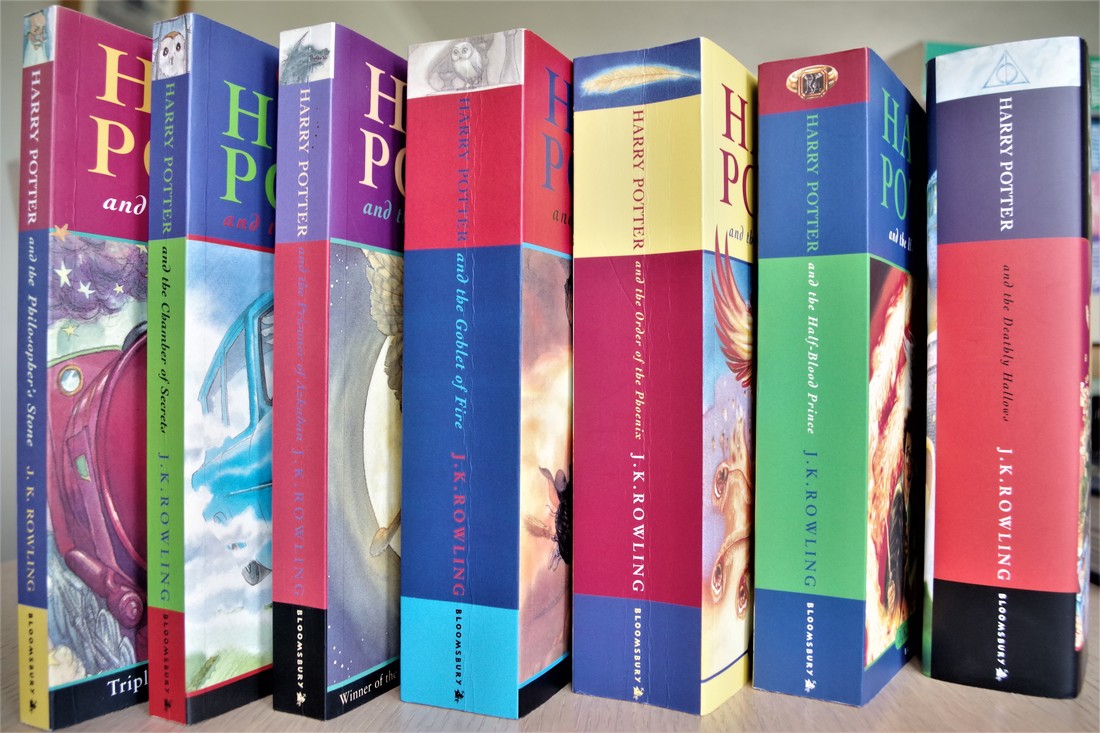

The book is divided into themed sections, covering a vast array of subjects such as magic, flora and fauna, deities, geometry, numbers and landscape. I love using symbolism in my novels, and found this book extremely helpful as a guide and a source of fresh ideas – the structure makes it easy to dip into, and although in some areas it might be necessary to carry out more detailed research, there is a lot of depth to certain sections, for example the pages for tarot and astrology. I’ve continued to use The illustrated Signs and Symbols Sourcebook for the research and planning of my latest novel, Second Sun, and I’m sure this will remain a well-thumbed tome for many more years and books to come! I have long loved reading fantasy novels, and many of them have significantly influenced my own writing. I enjoy books in this genre for their exciting plots, their memorable characters, the sense of escapism and their bold, challenging ideas - and I have tried to achieve these in my own work. I have too many favourite fantasy books to possibly discuss in one blog post (honourable mentions for books just missing out from my list include the staggering Mythago Wood by Robert Holdstock, His Dark Materials by Philip Pullman and Elidor by Alan Garner) and I have blogged previously about the massive influence of J.R.R. Tolkien on my writing (you can read the post here) but I thought I would discuss some of the fantasy novels that have most influenced and inspired me. Memory, Sorrow and Thorn - Tad Williams I have read and enjoyed many epic fantasy series, and although often enjoyable, many appear to be reheated versions of The Lord of the Rings, recycling many of the same elements. With an epic secondary world (Osten Ard), complex plotting, a cast of hundreds, battles and fantastical monsters, Memory, Sorrow and Thorn could, on the surface, be yet another fantasy saga descended from the Tolkien tradition, but in many ways it reverses key elements and tropes of The Lord of the Rings. For example, yes, there is a Dark Lord – the Sithi Storm King – but for all his evil, his actions are largely in response to appalling suffering inflicted upon his people. Good and evil within Osten Ard cannot be identified solely by race or country – there are few easy answers in this land and there are troubling, nightmarish secrets to be uncovered… I read each volume of Memory, Sorrow and Thorn over several weeks and found the whole saga utterly absorbing. It is so intelligently and boldly constructed, and challenges many of the assumptions of the genre – but please do not think it is a dry read; far from it, there are many thrilling moments and the characters are three dimensional and memorable. Rather than reheating Tolkien’s masterpiece, Tad Williams’s series builds upon the foundations of the genre to create something original and truly special. Harry Potter – J.K. Rowling The joy of reading as a child is a different, perhaps more intense, experience than that of reading as an adult. I can remember spending many happy hours reading books such as Watership Down and The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, and the frustration when I had to put the book down for a meal or for sleep! I was (obviously!) too old to read the Harry Potter books as a child, but the story still engrossed me. The sheer quality of the storytelling – the superb plotting and rich characterisation – cannot be denied. J.K. Rowling’s magical universe is beautifully realised, drawing cleverly upon her knowledge of mythology, folklore and alchemy. Rowling’s books should serve as an inspiration to any writer – they are written with love, with passion and a fierce determination to explore important themes about life, death, power and the importance of love and friendship. I wonder how many children have had a lifelong love of reading sparked by the Harry Potter books? I feel certain that J.K. Rowling's books will love a wonderful legacy. And for me, it is now a great joy to see my daughter fall in love the stories and the vivid characters within – she has so many exciting things to discover in the world of Harry Potter! The Royal Changeling – John Whitbourn This is a hugely enjoyable tale set in an alternate seventeenth century England. Charles II, the Duke of Monmouth and even King Arthur appear, along with a host of supernatural characters – laced with witty, black humour, the story is briskly told and the period is wonderfully evoked. This mix of history and fantasy has been a great influence on my writing: for example, for The Tree of Life trilogy, reading The Royal Changeling encouraged me to set the series outside of the traditional fantasy medieval setting - mixing muskets and monsters felt, for me, a delicious combination! I cannot recommend The Royal Changeling enough, and I would love to see the book, and Whitbourn’s other work, better known. Gormenghast trilogy – Mervyn Peake The visionary artist and writer Mervyn Peake’s majestic creation is often compared to The Lord of the Rings, but it is a very different beast. A work of staggering originality, dreamlike, layered and gothic, and full of memorable imagery, the Gormenghast trilogy is truly a book to lose yourself in. It contains some of the best descriptive writing I have read, with the massive crumbling edifice of Gormenghast castle brought vividly to life, as is the madness of the ritual-ridden society dwelling within.

The characters – Lord Sepulchrave, Flay, Swelter, Steerpike and Fuchsia, to name just a few – stayed with me long after reading the books. Yes, they are larger than life, but their foibles and failings are only too human, and all the more troubling for this. I continue to be awed by the scale and ambition of Peake’s achievement, and I feel sure the Gormenghast trilogy will continue to be discovered and enjoyed by generations to come. What is your favourite fantasy novel? Leave a comment and join the conversation. If you’re interested in my writing, you can get the ebook version of my first novel - The Map of the Known World – for FREE, from Amazon, Nook, Kobo, iBooks or Smashwords. I have also previously blogged about the reasons why I write fantasy fiction - check out the blog post here. |

Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed