|

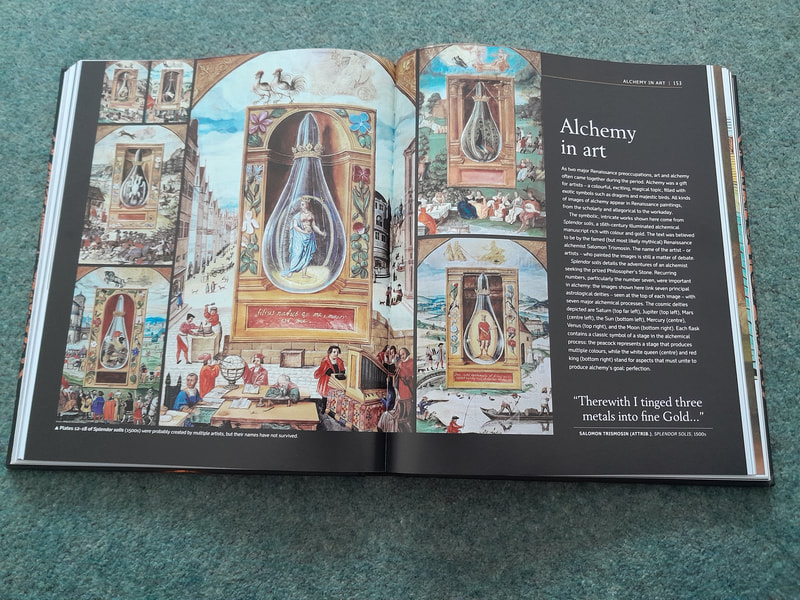

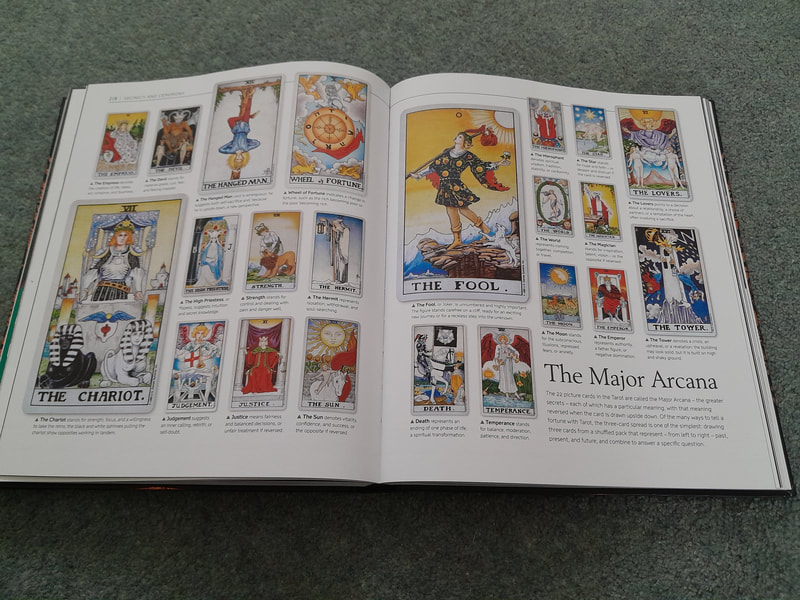

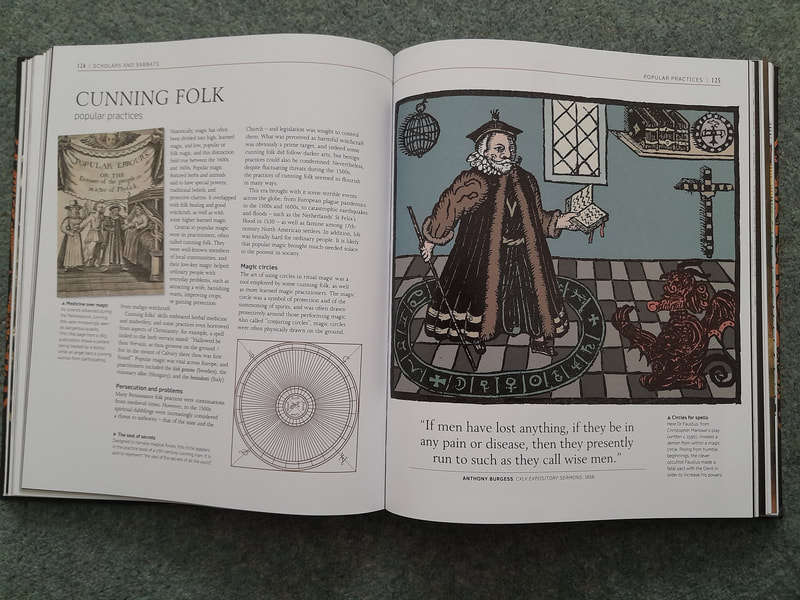

Professor Suzannah Lipscomb’s excellent foreword to A History of Magic, Witchcraft & the Occult sets the tone for this fascinating book, which explores how humans have sought to understand the universe and their place within it, and how they can appease or control spiritual forces to influence their environment. As seems to be standard with DK titles, the book is beautifully designed, with lavish illustrations (including paintings, photographs and woodcuts) and quick-fact panels to define and explain key information. The book is an intriguing journey through magical history, travelling from prehistoric times to the modern world, encompassing divination, alchemy, shamanism, Wicca and so much more. The broad historical narrative unfolds chronologically and takes a global view, drawing on cultures, beliefs and practices from across the world. There are many highlights I could mention, but I found the chapters on Mesopotamian magic (I’d also recommend The First Ghosts by Irving Finkel on this topic) and Renaissance folk magic especially engrossing. I bought the book as part of research for my latest novel, and while it has certainly proved useful in that regard, it is also a pleasure to read and there is always something unexpected to find. The sheer scope of the book inevitably means the subjects are not explored in great depth, but there is enough detail to interest the reader and to encourage further and research.

A History of Magic, Witchcraft & the Occult gives the reader a good sense of the important role magical practices and beliefs have played in shaping civilisations around the world, and the ways in which they continue to enrich many people’s lives. So, whether you’re looking to discover more about the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, Mayan cosmic cycles, tarot or countless other magical subjects, you’ll find something in this book to spark your imagination or inspire your creativity. If you’re interested in learning more about the history of magic, I would also recommend The History of Magic by Chris Gosden (which gives a more in-depth survey of the subject, and which I reviewed in a previous blog post), and from a British perspective, Pagan Britain by Professor Ronald Hutton and The Book of English Magic by Philip Carr-Gomm and Richard Heygate.

0 Comments

The Stand has long been on my ‘to read’ list and I am glad to have finally read this epic thriller from Stephen King. The early stages of the novel are post-apocalyptic, as a manmade flu-like virus is accidently released from a top-secret US military laboratory, causing a catastrophic pandemic. Despite frantic, belated efforts by the government and the army to contain the outbreak, including brutal enforcement of martial law, 99% of humans die from the virus, and King vividly portrays the terror and despair as civilisation rapidly collapses – one scene that will stay with me is Larry Underwood’s nightmarish journey through the Lincoln Tunnel, a moment of visceral horror and tension. As the traumatised, often grief-stricken survivors try to regroup and make sense of their disintegrating world, The Stand moves towards more of a dark fantasy, and the shattered remnants of the United States gradually becomes the setting for an epic struggle between good and evil, and fear and paranoia become as deadly foes as the virus itself. For the survivors begin having strange dreams: either of a kindly, aged prophetess, Mother Abigail or of the ‘dark man’, Randall Flagg. Mother Abigail leads her followers to Boulder, Colorado, where they start to rebuild a society, facing challenges such as restoring the power, providing medical care (I felt sorry for Dick Ellis, the overworked veterinarian who is initially the only ‘doctor’ in the community) and shaping an effective government. Meanwhile, the demonic Randall Flagg beckons followers to his growing empire formed around Las Vegas, including murderer Lloyd Henreid (who Flagg rescues from prison and cannibalism…) and the pyromaniac Trashcan Man. And the stage is set for a struggle between the two communities, and the future of humanity… The Stand is a powerful, frequently disturbing novel, but at its core it is driven by insightful human details, which gives the book real emotional impact. One character I found especially interesting was Harold Lauder – he had been a social outcast at school and retains an obsessive love for Frannie Goldsmith, with whom he travelled to Boulder. (Minor spoiler alert) Despite becoming a valued and respected member of the community, Lauder cannot let go of the difficulties and rejections of his past, internal wounds that begin to lead him down a dark path. Harold Lauder is a complex character and is written with such skill by King, we can see how Lauder is twisted by a sense of betrayal, placing vengeance for past humiliations above embracing a new life for himself.

I also enjoyed the scene (again, minor spoiler alert) when Glen Bateman, a retired professor of sociology comes face-to-face with the demonic Randall Flagg – this moment is a powerful demonstration of how brittle authoritarian power can be when faced with mockery. Reading The Stand requires a significant time commitment from the reader, but in my experience, it was absolutely worth the effort. It is a gripping novel of huge power, encompassing fantasy, adventure, horror and much more, and from the first page you’re safely in the hands of a master storyteller. It is a long novel (and I read the extended / revised version) but for me the story never dragged and the scope of the novel justified the page-count. There is always a large number of characters in play, but the majority are so richly developed they are memorable as well as being key to propelling forward the plot. I have read (embarrassingly) little of Stephen King’s work before tackling The Stand, but I am definitely hooked now! I have just started reading The Dark Tower and look forward to losing myself in another epic dark fantasy… The Prince in Waiting trilogy (aka Sword of the Spirits) is an epic post-apocalyptic fantasy series from John Christopher, the author of books such as The Tripods and The Death of Grass. In a future Britain shattered by the Disaster (the true nature of which is revealed during the story), society has reverted to a medieval form, with the machines of the past rejected and reviled as the causes of the Disaster – anyone unwise enough to meddle with ‘ancient’ technology is put to death. All spiritual matters are dictated by the monastic-like Seers, whose role it is to interpret the will of the ‘Spirits’; Christians exist but as a marginal, often hated minority. Following the Disaster, birth defects are more common, leading to strict castes in society, with ‘true men’. ‘dwarfs’, who are permitted to work as blacksmiths to forge weapons, and the lowest social group, ‘polymufs’, who are denied many freedoms and are assigned the most menial tasks and treated as slaves. The protagonist of the books (I hesitate to say hero) is Luke, who lives in the walled city of Winchester, a powerful, militaristic realm, which regularly goes to war with neighbouring settlements. Luke becomes the Prince in Waiting, heir to the ruler of Winchester, but more than this, the Seers have planned he will be the one to unite the warring cities.

But Luke is a flawed choice – for all his undoubted bravery and fighting skills, he is ambitious, stubborn and proud, demanding complete loyalty from his subjects, especially from his closest friends. The world of this story is a treacherous one, with allies swiftly turning into enemies, and although Luke’s courage and warlike nature leads him to victories, his desire to avenge any perceived slight, any hint of disloyalty, leads him down a dark path… Consisting of three books, The Prince in Waiting, Beyond the Burning Lands and The Sword of the Spirits, this is an epic series, which cleverly threads in mythology (there’s a witty use of the tale of Tristan and Isolde at a key moment in the story), religion and science into a post-apocalyptic world. Some of the other tribes and settlements Luke encounters on his various journeys are unsettling and sometimes plain bizarre. I found Christopher’s portrayal of a violent fractured society, with dangers around every corner, compelling and the story is taut and brisk, with new wonders, and new horrors, emerging with each chapter. If you’re a fan of post-apocalyptic science fiction / fantasy, then this is certainly a series you would enjoy – I wouldn’t rate it quite as highly as John Christopher’s incredible Tripods Trilogy (which I have written about previously in this blog) but it is a fascinating companion piece and a worthwhile read in its own right. If you’re interested in finding out more about John Christopher / Sam Youd, I strongly recommend visiting the Syle Press website, which is packed with information and resources about the author and his books. In the summer of 1962, with his mother recuperating from an illness, young Luke Kirby is sent to stay with his Uncle Elias, (who Luke has never met) in a village called Lunstead. Elias soon reveals himself to be a magician, and he is keen to pass his skills onto his nephew. But as Luke begins his magical apprenticeship, a deadly horror reveals itself… Written by Alan McKenzie, and illustrated by John Ridgway and Steve Parkhouse, Summer Magic: The Complete Journal of Luke Kirby is a collection of tales (originally printed in 2000AD), which coalesce into an overall story arc. The stories are varied, for example: The Night Walker, where Luke must confront a vampire; Sympathy for the Devil, where Luke travels to hell (an unnervingly original version of the underworld) in search of his father; and (possibly my favourite in the book) The Old Straight Track, which delves deep into British mythology and folklore, becoming a memorable folk horror tale infused with paganism, during which Luke—guided by the mysterious alchemist called Zeke— travels through a landscape marked by ley lines, stone circles and long barrows. For me, there are echoes of the work of Alan Garner with the close connection between the landscape and the characters. Summer Magic is a compelling collection, with stories that in places pack a disturbing punch. Throughout the book, the beauty and mystery of the English countryside is beautifully evoked through the writing and the stunning artwork. And beneath that beauty, and within the sleepy streets of the villages and little towns, true horrors lurk… Through all the stories run themes of death, family and horror, and as Luke develops his magical and alchemical skills, he learns that all actions, however well-intentioned, have consequences. Within Summer Magic, there is more than a little sense of the challenging, hard-edged fare of 1970s British cinema and TV (this is definitely a story for the Scarred for Life generation). Summer Magic: The Complete Journal of Luke Kirby is a great collection—a coming-of-age tale but with a 2000AD edge, an excellent example of the dazzling range of creativity that has poured from the comic’s pages over the decades. If you’re read and reread all of the Harry Potter books, or just finished binge-watching series 4 of Stranger Things, you will find much to enjoy in this dose of Summer Magic. If you want to find out more about Summer Magic: The Complete Journal of Luke Kirby, I'd recommend this excellent short introductory video made by 2000AD: Greybeard is a science fiction novel by the British author Brian Aldiss, published in 1964. In 1981 humans and most mammals were rendered sterile by the ‘Accident’. By 2029, the youngest generation of humans are in their fifties, with no younger generations to follow. With civilisation collapsed, the remaining people eke out an existence in small, fearful communities, knowing humanity’s ultimate demise is close at hand. Greybeard (real name Algy Timberland) and his wife Martha abandon their crumbling settlement and set-off on a boat trip down the Thames, travelling through a landscape changed by the collapse of human civilisation and the resurgence of nature. Along the way Greybeard and Martha encounter other, strange communities, where the inhabitants often fall prey to profiteering hucksters and false prophets seeking to exploit the desperate need for hope in a fallen world. Foremost among such charlatans is the gloriously named Bunny Jingadangelow, who claims to possess the secrets of youth and immortality—when Greybeard and Martha encounter Jingadangelow later in the story, he has elevated himself as a religious figure, the Master, and through a mix of charm, deception and cunning, has gathered loyal followers who treat him like a god. As well as following Greybeard’s and Martha’s journey, flashbacks explore the effects of the self-inflicted ‘Accident’: the war, the descent into anarchy, the disease, the madness. The chapter where Greybeard and Martha encounter local tyrant Peter Croucher I found especially striking and darkly comic, as Croucher tries to enforce a brutal order after the national government in Britain disintegrates—Croucher is power-hungry, humourless and insecure, as witnessed by his fear of intellectuals and his mangled attempts to prove his own intelligence. The rise to power of such a figure in chaotic times is painfully plausible and carries a warning we should all heed.

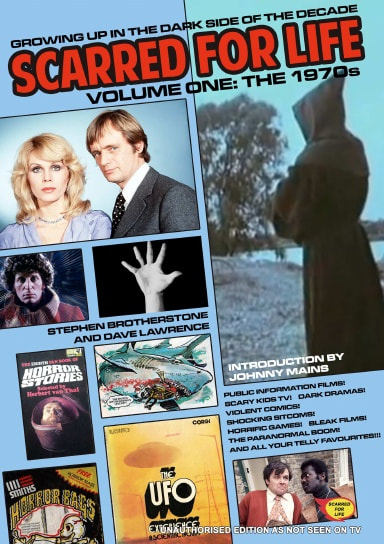

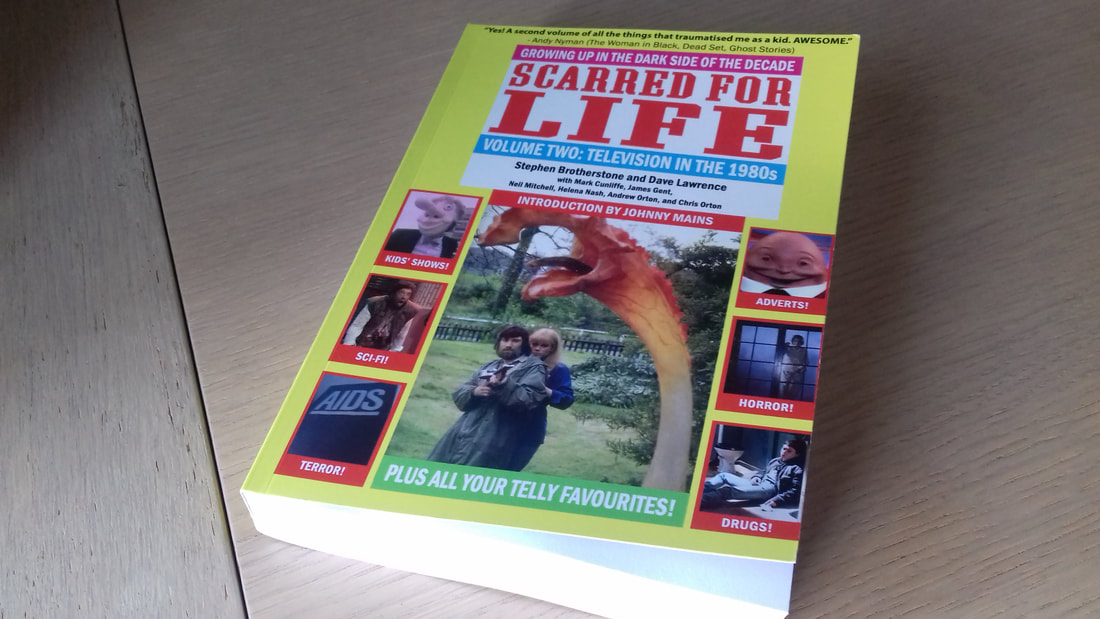

This is a haunting and sombre book, with a memorable depiction of a slow, quiet but unstoppable human catastrophe. The world of Greybeard is richly described, with a continual and potent contrast between the vigour and fecundity of nature (as it covers over roads and buildings, reoccupying lands previously lost to humans) and the decrepitude of humanity. There is the sense that the rule of humans is but a brief interruption and that nature might in time erase all trace of our species. Despite the bleakness, there are tiny slivers of hope, with rumours and sightings of humanoid beings—for example, the talk of elves and gnomes hiding in the forests—suggesting there might be a future for humanity, albeit one very different from what came before. Exploring themes of aging, death, religion and power, Greybeard is a powerful and thought-provoking novel from a master of science fiction. Book review: Scarred for Life (Volumes One and Two) by Stephen Brotherstone and Dave Lawrence9/8/2022 There’s no doubt some of the popular culture in Britain during the 1970s and 1980s was, well, different; in fact, it was often dark and unnerving, with scary television programmes, frightening films and books, and frankly terrifying Public Information Films (I had few more unnerving viewing experiences in childhood than having to watch Apaches at Primary School)—it is this creepy, unsettling sense that it is captured and discussed perfectly by Volumes One and Two of Scarred for Life. Volume One covers a wide range of subjects: scary television, films, books, the paranormal, games and much, much more. A flavour of what’s discussed includes Doctor Who, Children of the Stones, Folk Horror, Watership Down, 2000AD and the Pan Books of Horror Stories. I could go into far more detail but it’s better to leave it to you to explore as a reader and discover the book’s treasures for yourself. Volume Two is focused on the darker side of 1980s television, and there’s plenty of ground to cover! A couple of personal favourites covered in detail include two excellent BBC adaptations of SF books: the bold (though sadly unfinished) adaptation of John Christopher’s The Tripods and the chilling version of John Wyndham’s The Day of the Triffids (the opening credits alone frightened me as a child!). Volume Two digs deep into topics such as children’s television (how did I not see Knights of God at the time? Sounds exactly like the sort of programme I would have loved then and now!), surreal drama, the impact of Channel 4 and yes, more terrifying Public Information films! As Volume One does with the 1970s, I found that Volume Two, as well as being a fantastic exploration of 1980s popular culture, also gives a vivid sense of what life in Britain was like then, both the good and the bad. Each volume of Scarred for Life goes deep into detail on the many subjects, but don’t think for a minute these are dry reads—the writing throughout is energetic, honest and often funny. Both books are mighty tomes, and as well as being great reads, the suggested viewing section that accompanies many of the chapters sent me off to YouTube to watch various clips and programmes. That writing these books was a labour of love by the authors and other contributors shines through on every page. For me, the first two volumes of Scarred for Life represent independent publishing at its very best; bold, informed and passionate. I can’t recommend both volumes of Scarred for Life enough, and look forward to the publication of volume three. If you want to get hold of Scarred for Life volumes one and two (and if possible, you certainly should), they are available from the links below:

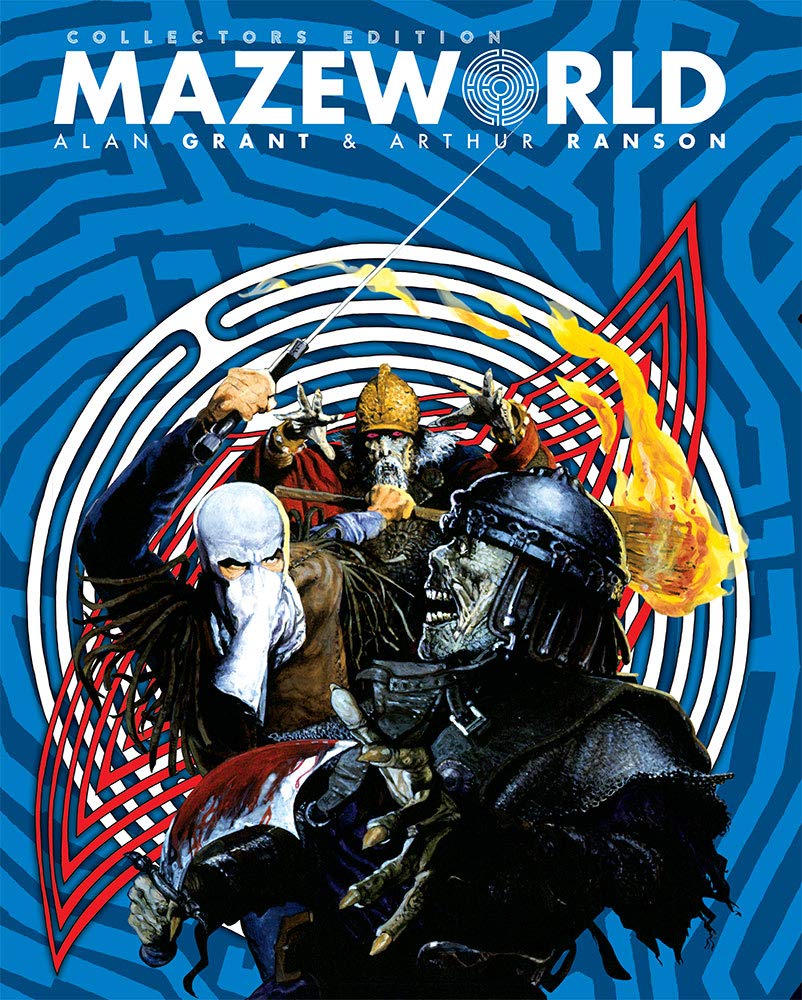

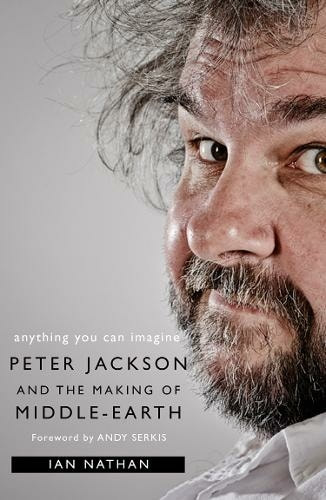

Scarred for Life – Volume one Scarred for Life – Volume two It is also worth following the Scarred for Life account on twitter, both for some great content and for regular discount offers on both books. Happy reading and happy nightmares... Britain has brought back the death penalty, and Adam Cadman, convicted of murder, finds himself the first person to be hanged since 1964. But as the noose tightens around his neck, Cadman is transported to the Mazeworld, a world in another dimension, and there this reluctant hero begins his adventure. For in this world of strange creatures and mighty warriors, Cadman is believed to be the Hooded One, a hero of old who can lead the oppressed masses in rebellion against the Mazeworld’s cruel masters… It’s been a long time since I last dipped into the wild and weird world of 2000AD; although not a regular reader of the comic as a young person, characters such as Nemesis the Warlock left an indelible memory. I decided to start my journey through 2000AD classics with Mazeworld, and I was not disappointed. Written by Alan Grant and illustrated by Arthur Ranson, Mazeworld is truly a work of epic fantasy, bold and imaginative. There is action aplenty, all expertly paced and beautifully illustrated – the artwork of Arthur Ranson is always stunning and at times simply breathtaking. Some of the panels could be frames from epic movies, full of energy and excitement. It is a powerful story too, thematically dense, and rich in mythological and folkloric imagery such as the Green Man. The world building is staggering - the architecture of this other dimension, inspired by the Aztec and ancient Egyptian cultures, looms over the panels, almost making the Mazeworld a character in its own right, with visual treats such as the enormous ziggurats, the many carved monuments to old gods who look on in silent judgement, and the twisted alleyways and dungeons. The gritty rundown realism of the Mazeworld plays effectively alongside the broader fantasy elements such as maze monsters and flying lizards – this serves to make the world of the story all the more convincing and immersive. Cadman is certainly far from the traditional hero – upon his first ‘arrival’ in the Mazeworld he is a coward, concerned only with his own welfare and interests; but gradually, through many trials and failures, he begins to develop into the hero the suffering folk of the Mazeworld so desperately crave. Mazeworld offers an unsettling vision of evil - the enemies Cadman face in this other dimension are truly horrific, from the scheming Lord Raven, to the spine-chilling Dark Man with his deadly third eye, and the final demonic foe… Atmospheric and immersive, Mazeworld is a treat for any lover of fantasy fiction and tales of the uncanny. I was so engrossed in the unfolding plot, I am sure there are many subtleties I missed, so I look forward to discovering them when I re-read the book and once more become lost in the Mazeworld. If you want find out more about Mazeworld, I'd recommend an excellent short introductory video made by 2000AD: Book review: Anything you can imagine - Peter Jackson and the making of Middle Earth, by Ian Nathan7/5/2021 I can vividly remember the first time I watched The Fellowship of the Ring – in a packed cinema, with an excited and expectant audience. I’d been counting down the weeks, the days, the hours to the opening of the film. I’d long been a huge admirer of J.R.R. Tolkien’s work, and a trilogy of films based on The Lord of the Rings was something I’d dreamed of for years. However, my excitement was tempered by a twinge of trepidation – surely no film could truly capture the depth of Tolkien’s epic, surely no-one could bring Middle-Earth to life on the screen? Well, with Frodo and friends in Peter Jackson’s safe hands, I need not have feared. Like millions of others, I was enthralled by The Fellowship of the Ring – a film beautifully designed and superbly acted, with moments that chimed perfectly with the book, such as the bucolic Shire, the fearsome Black Riders and the film’s (arguably the trilogy’s) highlight sequence, the Mines of Moria, especially the mighty Balrog. As soon as The Fellowship of the Ring ended, I wanted to see it again, and of course, looked eagerly forward to seeing The Two Towers and The Return of the King, both of which proved to be sublime cinematic achievements in their own right. Anything you can imagine tells the story of how these wonderful films came to be made, and it is a fascinating tale. The book gives insights into the lengthy and complex creative process, as well as the Byzantine twists and turns of the film industry. The journey of the film from Peter Jackson’s and Fran Walsh’s initial idea of adapting The Lord of the Rings to the final, final green light for the project is deeply interesting, a winding route encompassing King Kong, Miramax and the Weinstein brothers (shudder), to the dramatic intervention of New Line Films, and their bold, unprecedented decision to make three films back-to-back. It almost reads like a thriller and one can only admire the tenacity of Jackson and his colleagues to bring the project to fruition where surely many others would have given up.

Nathan also superbly tracks the fascinating ascent of Peter Jackson from maverick, self-taught director of low budget splatter films, through to the blossoming of his talent in pictures such as Heavenly Creatures, to eventually becoming one of the world’s most successful movie-makers. Once the book moves into the nuts and bolts detail of actually making The Lord of the Rings film, I found it lost a little of its focus and strong narrative, but it always remains highly readable and reflects the enormous challenges and sheer scale of creativity involved in bringing the films to life. From the groundbreaking special effects (such as the MASSIVE software used to help portray the epic battles, and the creation of Gollum), the stunning sets, and the music of Howard Shore, truly one of the great triumphs of the film trilogy, the scale of what was accomplished, often pushing film-making into new areas, becomes clear. Peter Jackson is the conductor of this great orchestra, but Nathan rightly makes sure credit is given to the many others, especially his redoubtable fellowship of Kiwi collaborators, who surmount problem after problem, refuse to submit to the project’s many naysayers, and doggedly drained every last ounce of creativity and energy to make the best possible version of Tolkien’s masterpiece. The book treads more lightly on the generally less-loved The Hobbit trilogy, but gives an absorbing insight into the legal, logistical and creative issues in the troubled gestation and production of these films. And for all the flaws of The Hobbit trilogy, and I confess they leave me a little cold, Nathan rightly acknowledges their successful elements, such as the performances of Martin Freeman and Ian McKellen, the often stunning visuals, and the memorable depiction of Smaug. It’s difficult to imagine a more daunting cinematic journey to document than The Lord of the Rings trilogy, but Nathan succeeds with flair and humour, and his passion for these films, and for cinema in general, shines through on every page. I’d strongly recommend Anything you can imagine for anyone interested in The Lord of the Rings films or just in movie-making in general. And having read this book, I now want to watch and enjoy all three films (extended editions, of course) all over again… “On my naming day when I come 12 I gone front spear and kilt a wyld board he parbly ben the las wyld pig on the Bundel Downs any how there hadnt ben none for a long time befor him nor I aint looking to see none agen.” Just from this quote – the opening words of the novel – you will see Riddley Walker is a book unlike any other. The novel is set hundreds of years in the future, long after a nuclear holocaust, with England reduced to effectively an Iron Age level of existence. When his father dies in an accident, young Riddley Walker inherits a shamanistic role among his people, and when he uncovers an attempt to recreate the weapons that once devastated civilization, he is forced to go on the run. Twelve years’ old, though perceptive beyond his tender years, Walker narrates his adventure in the fragmented, fractured Riddleyspeak, a language as broken as the society portrayed in the story. I found Riddleyspeak a challenge, especially in the early pages, but in time (and with the help of a glossary at the end of the book), I began to adapt to the rhythm and structure. You are forced to slow your reading, and if anything, I think the book would benefit from being read aloud.

The language reinforces the sense we are seeing Riddley’s post-apocalyptic world through his eyes, adding to the force and energy of his descriptions. Hoban’s invented language fizzes with clever word-play, and through this we see echoes of the past, and adds to the sense shared by Riddley and other characters in the story of the heights civilization once reached, and the bitterness and sense of shame that all was lost through human aggression and greedy misuse of their technological wonders. The language can, in places, be very funny, for example in the twisted Kent placenames (Do-it-over = Dover, Horny Boy = Herne Bay) and the scene where Goodparley and Riddley attempt to interpret The Legend of Saint Eustace (written as it is in modern English). Riddley’s adventurous journey allows Hoban to build a grim portrayal of this ruined England, from the mysterious Eusa folk, the ruined cathedral in Cambry (Canterbury), the wandering packs of wild dogs and the Eusa Show, performed by the ‘Pry Mincer’ and the ‘Wes Mincer’, who on their travelling puppet shows perform allegorical propaganda stories to the , communities. It is an uncompromising vision, and as bleak and well-conceived a dystopia as I have ever encountered. Infused with mythological, folkloric and religious symbolism, Riddley Walker is rich for endless interpretation; it is not an easy read, but it is worth the effort – Trubba not. I would also add the edition of Riddley Walker I read had an entertaining introduction by novelist Will Self, which provided some valuable insights and context. If you spend any time in the lonely places of the British countryside – the deserted beaches, the dense forests, the Fens, the hills and mountains, the still ponds and lakes, the ruins half-swallowed by time – then you’ll be familiar with the occasional fleeting sense of there being something just out of sight, just out of hearing, a sense of watchfulness, of secrets and trauma long-hidden. It is these wild places, and the effect they have on us, that Edward Parnell explores in his outstanding book Ghostland – In search of a Haunted Country. In the best way, Ghostland is a difficult work to categorize. It is a book of haunted landscapes and haunted lives, a book filled with folklore, natural history, psychogeography and cinematic and literary references, all underpinned by the author’s deeply moving personal story. Whether exploring the crumbling cliffs and lonely beaches of Suffolk, or the sprawling Glasgow Necropolis, or the rugged coast and Neolithic moorlands of West Cornwall, and many locations in between, Parnell invokes a powerful sense of place and the stories and ghosts that surround and infuse them. Ghostland shines a light on some of Britain’s finest writers of horror and the uncanny, such as M.R. James, William Hope Hodgson, Arthur Machen and Alan Garner, showing how their obsessions and fears, and connections to their landscape, shaped their creations, often in unsettling ways. Although some of the authors mentioned in the book I am familiar with, there are others whose work I didn’t know, so one of the joys of Ghostland is discovering a list of novels and short stories I now can’t wait to read.

As well as ghostly literary tales, on-screen horrors are explored too, and not just folklore-inflected cinema and television such as The Wicker Man, The Children of the Stones and Jonathan Miller’s peerless M.R. James adaptation Whistle and I’ll Come To You (still an intense, disturbing experience), but also the dark strain of British public information films, which are vividly remembered, most likely in our personal and collective nightmares, by the generation exposed to them. For example, Lonely Water, a nightmarish warning of the perils of swimming in dangerous places (narrated with spine-tingling relish by Donald Pleasance), and Apaches, a terrifying short film I remember being shown at primary school – if the aim of Apaches had been to convince children growing up in rural Britain in the 1970s and 1980s that the countryside was filled with hidden and gruesome threats, then, from my perspective at least, it succeeded… I think anyone reading this book will find some moments of connection and resonance, whether in Parnell’s deep love and reverence for the natural world, his fascination with stories of the uncanny or in his sensitive but unflinching description of his own personal tragedies. For me, Ghostland demonstrates how our cherished places and stories – in any form – can help us manage and make sense of our real-life struggles. The best ghost stories don’t just frighten or excite us, they help to remind us to acknowledge painful memories – our own ghosts of the past – to help us move forward, to help us keep going, even when stricken with loss and grief. From the first page of Ghostland to the last, I fell under its haunted spell; I have no doubt it is a book I will revisit and reread, and I am sure every time I open it, I will find new treasures – and new horrors – buried within its pages. |

Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed