|

The Stand has long been on my ‘to read’ list and I am glad to have finally read this epic thriller from Stephen King. The early stages of the novel are post-apocalyptic, as a manmade flu-like virus is accidently released from a top-secret US military laboratory, causing a catastrophic pandemic. Despite frantic, belated efforts by the government and the army to contain the outbreak, including brutal enforcement of martial law, 99% of humans die from the virus, and King vividly portrays the terror and despair as civilisation rapidly collapses – one scene that will stay with me is Larry Underwood’s nightmarish journey through the Lincoln Tunnel, a moment of visceral horror and tension. As the traumatised, often grief-stricken survivors try to regroup and make sense of their disintegrating world, The Stand moves towards more of a dark fantasy, and the shattered remnants of the United States gradually becomes the setting for an epic struggle between good and evil, and fear and paranoia become as deadly foes as the virus itself. For the survivors begin having strange dreams: either of a kindly, aged prophetess, Mother Abigail or of the ‘dark man’, Randall Flagg. Mother Abigail leads her followers to Boulder, Colorado, where they start to rebuild a society, facing challenges such as restoring the power, providing medical care (I felt sorry for Dick Ellis, the overworked veterinarian who is initially the only ‘doctor’ in the community) and shaping an effective government. Meanwhile, the demonic Randall Flagg beckons followers to his growing empire formed around Las Vegas, including murderer Lloyd Henreid (who Flagg rescues from prison and cannibalism…) and the pyromaniac Trashcan Man. And the stage is set for a struggle between the two communities, and the future of humanity… The Stand is a powerful, frequently disturbing novel, but at its core it is driven by insightful human details, which gives the book real emotional impact. One character I found especially interesting was Harold Lauder – he had been a social outcast at school and retains an obsessive love for Frannie Goldsmith, with whom he travelled to Boulder. (Minor spoiler alert) Despite becoming a valued and respected member of the community, Lauder cannot let go of the difficulties and rejections of his past, internal wounds that begin to lead him down a dark path. Harold Lauder is a complex character and is written with such skill by King, we can see how Lauder is twisted by a sense of betrayal, placing vengeance for past humiliations above embracing a new life for himself.

I also enjoyed the scene (again, minor spoiler alert) when Glen Bateman, a retired professor of sociology comes face-to-face with the demonic Randall Flagg – this moment is a powerful demonstration of how brittle authoritarian power can be when faced with mockery. Reading The Stand requires a significant time commitment from the reader, but in my experience, it was absolutely worth the effort. It is a gripping novel of huge power, encompassing fantasy, adventure, horror and much more, and from the first page you’re safely in the hands of a master storyteller. It is a long novel (and I read the extended / revised version) but for me the story never dragged and the scope of the novel justified the page-count. There is always a large number of characters in play, but the majority are so richly developed they are memorable as well as being key to propelling forward the plot. I have read (embarrassingly) little of Stephen King’s work before tackling The Stand, but I am definitely hooked now! I have just started reading The Dark Tower and look forward to losing myself in another epic dark fantasy…

0 Comments

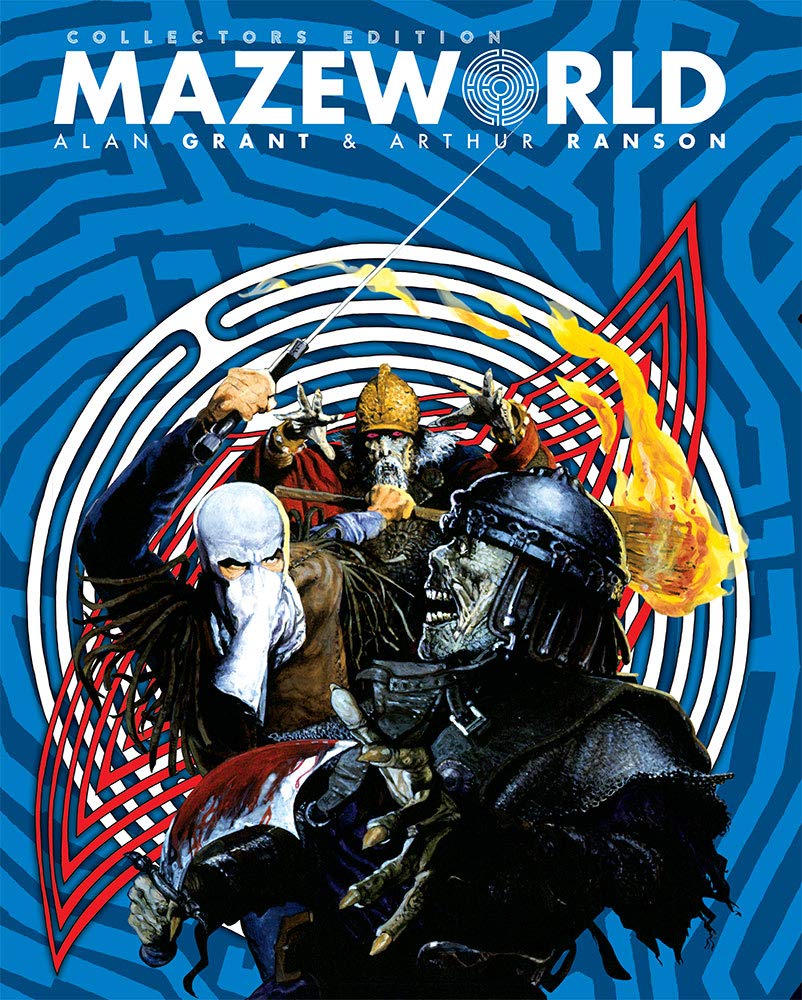

Britain has brought back the death penalty, and Adam Cadman, convicted of murder, finds himself the first person to be hanged since 1964. But as the noose tightens around his neck, Cadman is transported to the Mazeworld, a world in another dimension, and there this reluctant hero begins his adventure. For in this world of strange creatures and mighty warriors, Cadman is believed to be the Hooded One, a hero of old who can lead the oppressed masses in rebellion against the Mazeworld’s cruel masters… It’s been a long time since I last dipped into the wild and weird world of 2000AD; although not a regular reader of the comic as a young person, characters such as Nemesis the Warlock left an indelible memory. I decided to start my journey through 2000AD classics with Mazeworld, and I was not disappointed. Written by Alan Grant and illustrated by Arthur Ranson, Mazeworld is truly a work of epic fantasy, bold and imaginative. There is action aplenty, all expertly paced and beautifully illustrated – the artwork of Arthur Ranson is always stunning and at times simply breathtaking. Some of the panels could be frames from epic movies, full of energy and excitement. It is a powerful story too, thematically dense, and rich in mythological and folkloric imagery such as the Green Man. The world building is staggering - the architecture of this other dimension, inspired by the Aztec and ancient Egyptian cultures, looms over the panels, almost making the Mazeworld a character in its own right, with visual treats such as the enormous ziggurats, the many carved monuments to old gods who look on in silent judgement, and the twisted alleyways and dungeons. The gritty rundown realism of the Mazeworld plays effectively alongside the broader fantasy elements such as maze monsters and flying lizards – this serves to make the world of the story all the more convincing and immersive. Cadman is certainly far from the traditional hero – upon his first ‘arrival’ in the Mazeworld he is a coward, concerned only with his own welfare and interests; but gradually, through many trials and failures, he begins to develop into the hero the suffering folk of the Mazeworld so desperately crave. Mazeworld offers an unsettling vision of evil - the enemies Cadman face in this other dimension are truly horrific, from the scheming Lord Raven, to the spine-chilling Dark Man with his deadly third eye, and the final demonic foe… Atmospheric and immersive, Mazeworld is a treat for any lover of fantasy fiction and tales of the uncanny. I was so engrossed in the unfolding plot, I am sure there are many subtleties I missed, so I look forward to discovering them when I re-read the book and once more become lost in the Mazeworld. If you want find out more about Mazeworld, I'd recommend an excellent short introductory video made by 2000AD: Book review: Anything you can imagine - Peter Jackson and the making of Middle Earth, by Ian Nathan7/5/2021 I can vividly remember the first time I watched The Fellowship of the Ring – in a packed cinema, with an excited and expectant audience. I’d been counting down the weeks, the days, the hours to the opening of the film. I’d long been a huge admirer of J.R.R. Tolkien’s work, and a trilogy of films based on The Lord of the Rings was something I’d dreamed of for years. However, my excitement was tempered by a twinge of trepidation – surely no film could truly capture the depth of Tolkien’s epic, surely no-one could bring Middle-Earth to life on the screen? Well, with Frodo and friends in Peter Jackson’s safe hands, I need not have feared. Like millions of others, I was enthralled by The Fellowship of the Ring – a film beautifully designed and superbly acted, with moments that chimed perfectly with the book, such as the bucolic Shire, the fearsome Black Riders and the film’s (arguably the trilogy’s) highlight sequence, the Mines of Moria, especially the mighty Balrog. As soon as The Fellowship of the Ring ended, I wanted to see it again, and of course, looked eagerly forward to seeing The Two Towers and The Return of the King, both of which proved to be sublime cinematic achievements in their own right. Anything you can imagine tells the story of how these wonderful films came to be made, and it is a fascinating tale. The book gives insights into the lengthy and complex creative process, as well as the Byzantine twists and turns of the film industry. The journey of the film from Peter Jackson’s and Fran Walsh’s initial idea of adapting The Lord of the Rings to the final, final green light for the project is deeply interesting, a winding route encompassing King Kong, Miramax and the Weinstein brothers (shudder), to the dramatic intervention of New Line Films, and their bold, unprecedented decision to make three films back-to-back. It almost reads like a thriller and one can only admire the tenacity of Jackson and his colleagues to bring the project to fruition where surely many others would have given up.

Nathan also superbly tracks the fascinating ascent of Peter Jackson from maverick, self-taught director of low budget splatter films, through to the blossoming of his talent in pictures such as Heavenly Creatures, to eventually becoming one of the world’s most successful movie-makers. Once the book moves into the nuts and bolts detail of actually making The Lord of the Rings film, I found it lost a little of its focus and strong narrative, but it always remains highly readable and reflects the enormous challenges and sheer scale of creativity involved in bringing the films to life. From the groundbreaking special effects (such as the MASSIVE software used to help portray the epic battles, and the creation of Gollum), the stunning sets, and the music of Howard Shore, truly one of the great triumphs of the film trilogy, the scale of what was accomplished, often pushing film-making into new areas, becomes clear. Peter Jackson is the conductor of this great orchestra, but Nathan rightly makes sure credit is given to the many others, especially his redoubtable fellowship of Kiwi collaborators, who surmount problem after problem, refuse to submit to the project’s many naysayers, and doggedly drained every last ounce of creativity and energy to make the best possible version of Tolkien’s masterpiece. The book treads more lightly on the generally less-loved The Hobbit trilogy, but gives an absorbing insight into the legal, logistical and creative issues in the troubled gestation and production of these films. And for all the flaws of The Hobbit trilogy, and I confess they leave me a little cold, Nathan rightly acknowledges their successful elements, such as the performances of Martin Freeman and Ian McKellen, the often stunning visuals, and the memorable depiction of Smaug. It’s difficult to imagine a more daunting cinematic journey to document than The Lord of the Rings trilogy, but Nathan succeeds with flair and humour, and his passion for these films, and for cinema in general, shines through on every page. I’d strongly recommend Anything you can imagine for anyone interested in The Lord of the Rings films or just in movie-making in general. And having read this book, I now want to watch and enjoy all three films (extended editions, of course) all over again…

All authors draw on a wide range of inspirations when creating their stories, such as real-life experiences, places they have visited, concerns about the world and society, books they have read. For me, visual art has always inspired and influenced my writing. I cannot claim to be an expert in art history, and as much as I enjoy sketching my artistic skills are limited at best, but I find it an endlessly absorbing subject and a way of finding different perspectives on the world. By offering us a safe space to consider and explore feelings and fears we otherwise feel uncomfortable in confronting, art can help us all feel a little less alone in this world.

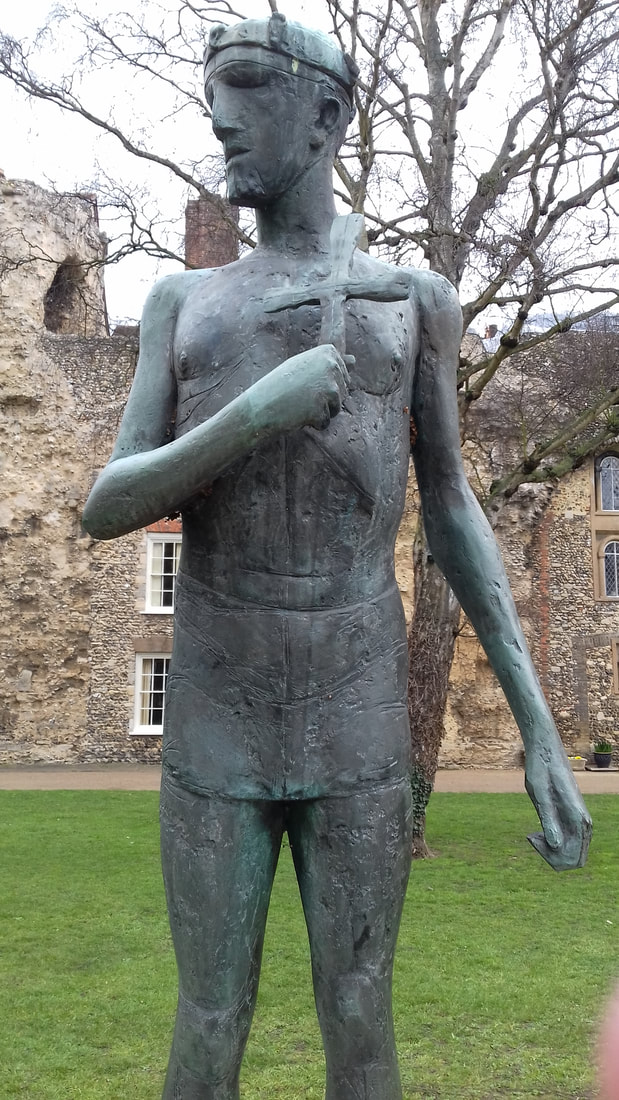

In this blog series, I am going to focus on four artists who have been particularly important to me and my creative work: Ian Miller, Elisabeth Frink, Paul Nash and Alfred Wallis. In this post, I am going to discuss the work of sculptor Elisabeth Frink. I first encountered the work of Dame Elisabeth Frink (1930-1993) in Bury St Edmunds in my home county of Suffolk. In the grounds of St Edmundsbury Cathedral stands a bronze statue of Edmund, a ninth century king of East Anglia.

After being defeated in battle by the Great Viking army, tradition says Edmund refused his enemies’ demand to renounce Christ and so was beaten, shot through with arrows and beheaded. Legend tells the Vikings threw Edmund’s severed head into the forest, but it was retrieved by those loyal to the king when they followed the cries of a mysterious wolf.

Frink’s statue shows King Edmund as a young man, a cross clasped in his hand. This is not a caricature of a warrior or a king – there is pride in Edmund’s face but a sense of vulnerability, his slender body is fragile. Frink’s Edmund is a king, a saint, a martyr, but still a human being. This combination of history, myth and human frailty seems to be present throughout much of Frink’s art. Born in Suffolk, Elisabeth Frink studied at the Guildford School of Art and was part of a post-war group of British sculptors, known as the Geometry of Fear School. Frink’s sculptures often depict men, birds, dogs and horses. My favourite work by Frink is Bird (1952). A few years ago I was lucky enough to visit the Tate St Ives, and of all the wonderful paintings and sculptures in the gallery, Bird stopped me in my tracks – with its alert, menacing stance and fierce beak, it seem to be an archetype of the hard tooth and claw of nature. Bird seems to channel a sense of ancient elemental forces, almost like a deity, a ferocious god demanding propitiation.

When writing my current novel, Second Sun, I was very taken by Frink’s goggle head sculptures; shaped by Frink’s interest in themes of masculine aggression, their sense of faceless authority very much shaped the look of the Shades, the cold, impersonal police force of my story. The goggle head sculptures avoid eye contact, concealed behind polished headgear – they are dehumanised and offer a threat that cannot be reasoned with.

I’m still learning more about Elisabeth Frink’s art, and I’m sure her work will remain enigmatic, unsettling and continually inspiring.

Part 1 - Ian Miller Part 2 - Alfred Wallis Part 4 - Paul Nash

If you’re interested in my writing, you can get the ebook version of my first novel - The Map of the Known World – for FREE. Please see the following Kindle preview:

All authors draw upon a wide range of inspirations when creating their stories, such as real-life experiences, places they have visited, concerns about the world and society, books they have read. For me, visual art has always inspired and influenced my writing. I cannot claim to be an expert in art history, and as much as I enjoy sketching, my artistic skills are limited at best, but I find it an endlessly absorbing subject and a way of finding different perspectives on the world. By offering us a safe space to consider and explore feelings and fears we otherwise feel uncomfortable in confronting, art can help us all feel a little less alone in this world.

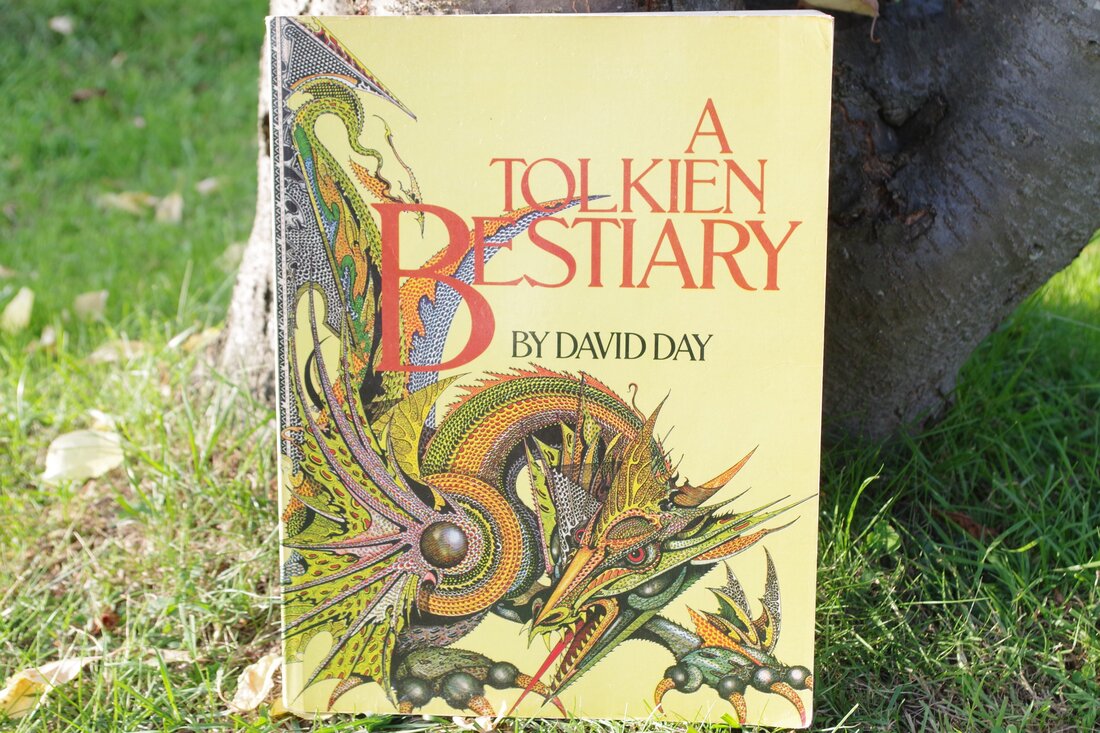

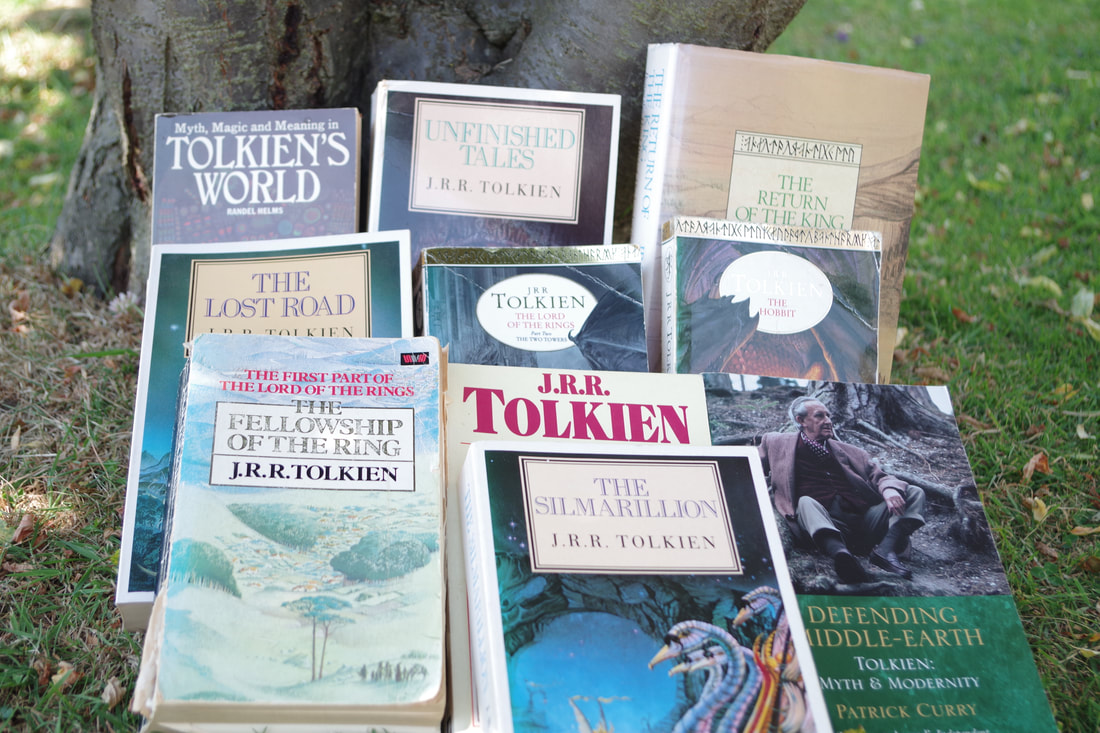

In this blog series, I am going to focus on four artists who have been particularly important to me and my creative work: Ian Miller, Elisabeth Frink, Paul Nash and Alfred Wallis. In this post, I am going to discuss the work of British fantasy artist Ian Miller. Since childhood I have loved the books of J.R.R. Tolkien, and my first encounter with the artwork of Ian Miller was in the book A Tolkien Bestiary; many beautiful and atmospheric images filled the pages of this book, but for me Miller’s illustrations stood out.

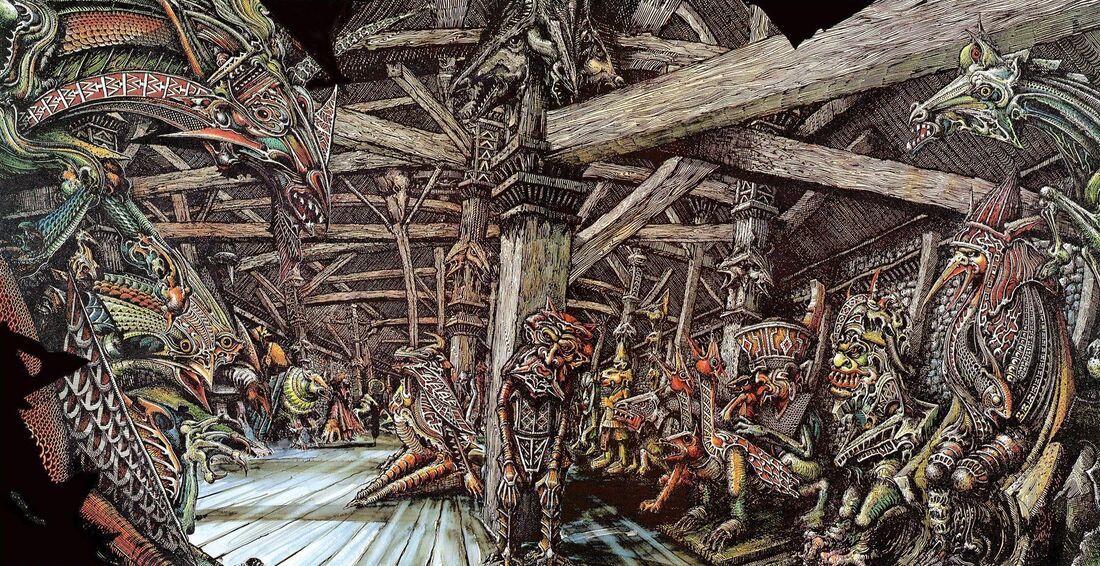

Whenever we read a novel we have our internal interpretations of the story, the setting and the characters, and I found in Miller’s images the darkness and intensity I’d always enjoyed in Tolkien’s books. For example, his portrayal of Helm’s Deep conveyed the terrifying scale of the battle, especially the monstrous, remorseless power of Saruman’s army – the whole image is so alive, I felt as though I could hear the battle, the clashing of steel, the drums, the screams. As with all Miller’s work, it boasts incredible detail, bursting with energy, two of the malevolent characters almost staring at, challenging, the viewer. When writing my epic fantasy Tree of Life trilogy, I wrote several battle scenes and I always keep this image of Helm’s Deep in my mind when doing so.

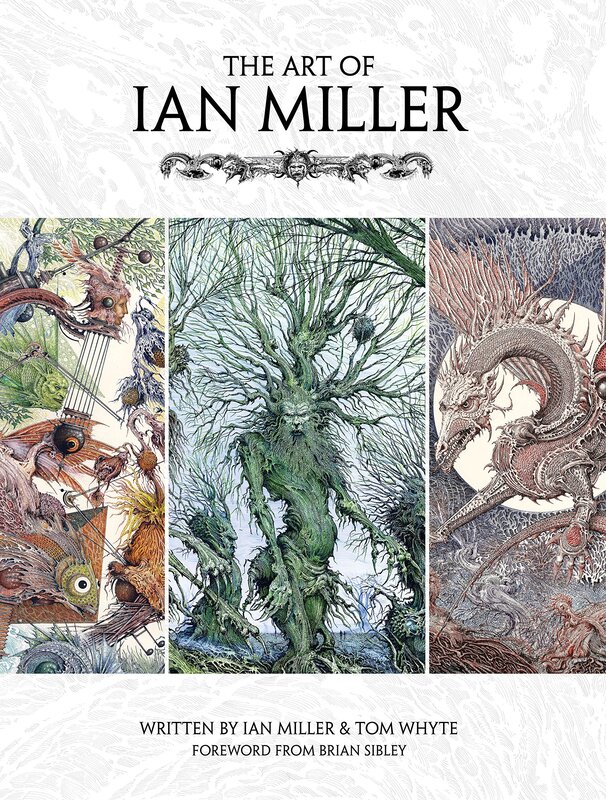

Born in 1946 and educated at St Martin’s School of Art, Ian Miller became one of Britain’s foremost fantasy illustrators. Known for his distinctive Gothic style, Miller’s work is immediately recognisable, and although profoundly original, I detect hints of Hieronymus Bosch, Pieter Bruegel the Elder and Albrecht Dürer in his work. Miller has worked on many book covers, including editions of H.P. Lovecraft’s stories and the Fighting Fantasy gamebooks. He contributed to Ralph Bakshi’s animated films, most notably the memorable post-apocalyptic science fantasy Wizards, where his macabre, richly detailed backgrounds added real atmosphere and a sense of depth.

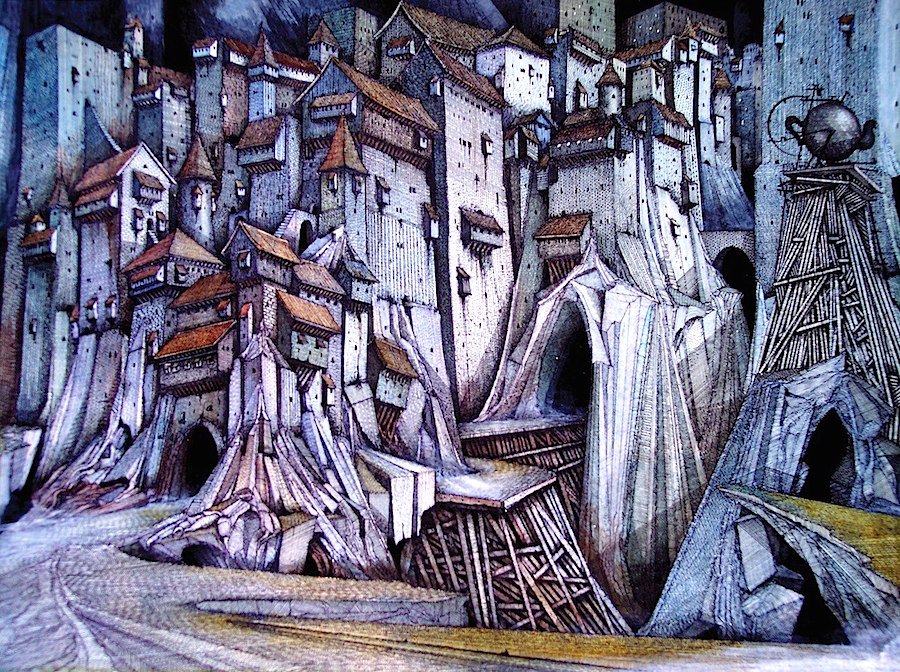

Miller also produced memorable illustrations inspired by Mervyn Peake’s classic series of Gormenghast books. Central to the story is the monstrous edifice of Gormenghast itself, whose ancient towers and mighty walls provide the ideal setting for the ritual-ridden people living there. Many of the characters inhabit the dank, damp corridors and rooms like ghosts, and the castle seems to be rotting and sinking. Through his dark, almost surreal style, Miller captures the slow decay of Gormenghast, hinting at the rising madness of the society within.

Miller once said:

“Rust, falling facades, tottering buttresses, and an overriding sense of impermanence, these are the things which fascinate me the most.” These objects of fascination coalesce in Miller’s Gormenghast illustrations, creating frightening but compelling visions that truly complement Peake’s Gothic masterpiece. The bold, often grotesque and nightmarish visions of Ian Miller lurk always somewhere in my imagination; whenever I write scenes set in forests full of gnarled trees or in crumbling buildings and edifices, I know they are in part inspired by Miller’s work. If you are interested in finding out more about Ian Miller, there is a collection of his artwork in the book ‘The Art of Ian Miller’, which showcases the sheer scale and depth of his creativity.

If you’re interested in my writing, you can get the ebook version of my first novel - The Map of the Known World – for FREE. Please see the following Kindle preview:

Writing a novel is a demanding exercise: it requires imagination, focus, and the stamina and enthusiasm to keep working over a long period. Moments of frustration, drudgery and disappointment are, unfortunately, all part of the process, but there is an even more difficult challenge to overcome – self-doubt. Self-doubt is the voice that whispers: ‘your writing is not good enough – you’re not good enough.’ It can slow your progress, even sinking you towards writer’s block (which I’ve posted about previously). To date, I’ve written four novels (and am drawing close to completion of a fifth) and numerous short stories; I’ve attended writing courses and have read many books on the subject; I’ve also advised and supported other writers on their writing and publication journeys. Despite this, I regularly feel a weighty amount of self-doubt when it comes to writing. The following is a selection of the doubts I often feel… These characters are flat. The story makes no sense. Nobody is ever going to want to read this. I’ve run out of ideas. And there are many, many more… At its worst, self-doubt stifles my creativity, making me hesitate rather than taking positive steps forward.

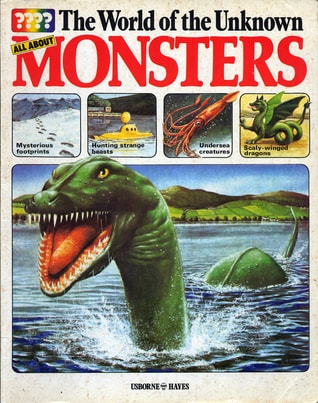

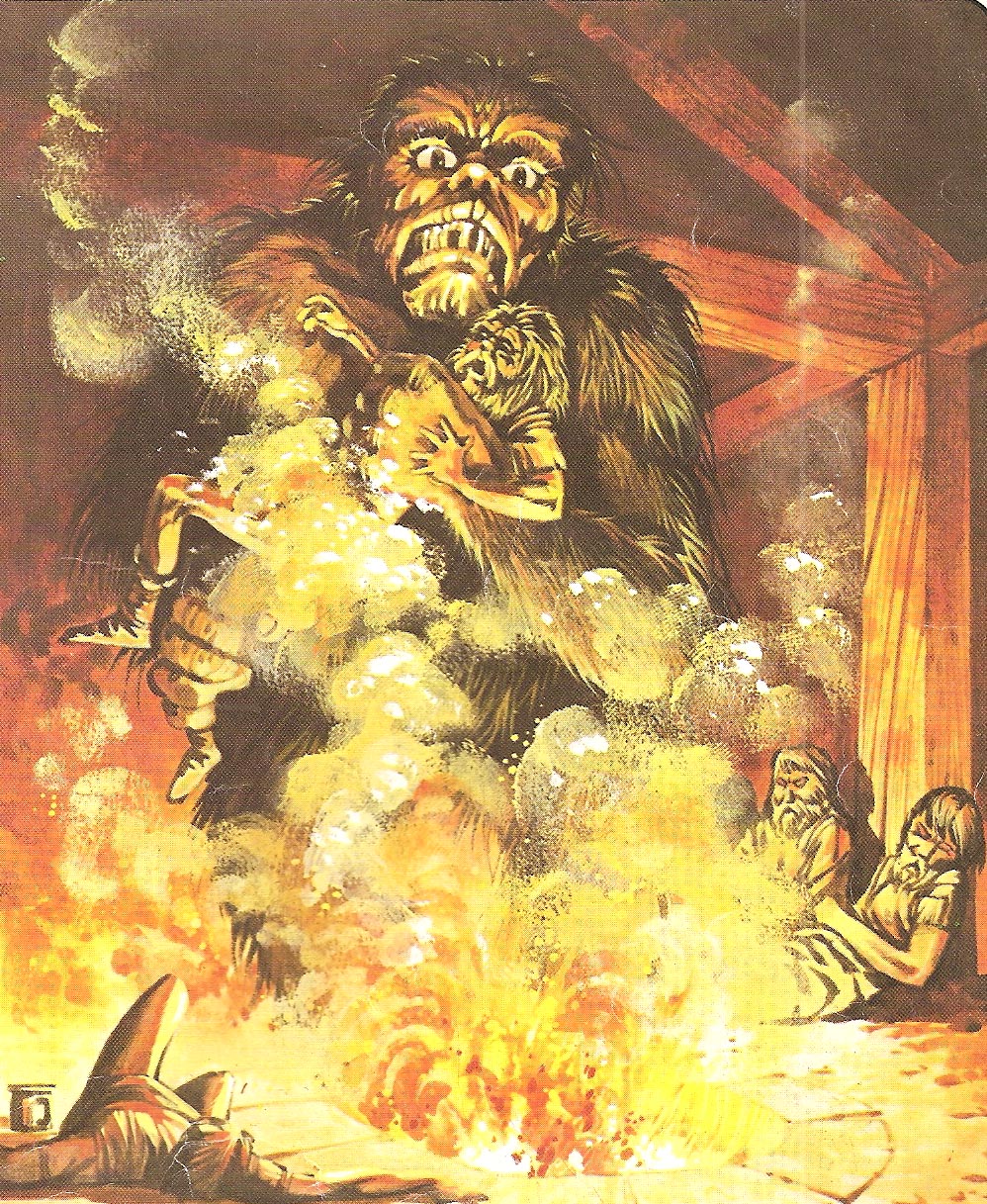

So, how can you overcome self-doubt? I’m not sure you can completely overcome it, but you can deal with it, and make sure it doesn’t stop you writing. Here are three tips: Manage your expectations: One advantage of self-doubt is that it challenges complacency: as a writer, it is healthy to have the ambition to keep improving your skills. However, there is a difference between ambition and expectation; the former is a positive, vital approach, the latter is a burden. An expectation can say ‘my writing must always be great’ - this sounds fair enough at face value, but dig a little deeper: is it reasonable to expect your writing to always be great? Of course it isn’t, but if you somehow believe this, then what is the inevitable outcome if your writing falls below par? You’ll feel like you are wasting your time, and that your work is worthless. This will only add further fuel to your inner self-critic, and this critic will do everything to convince you to stop writing. Cut yourself free from expectations – instead, just focus on trying to get better, trying to improve. Keep reading: Yes, it is tempting to compare yourself to other authors and when you read their books, their work will seem so polished, so impressive. But remember: their books have been fully developed, edited, proof-read – don’t compare them to your work in progress. So, keep reading as many books as possible – keep reading for inspiration and to learn more about different writing styles. Just keep going: When you’re hit by self-doubt, when your inner critic is at its most vocal, it is easy – and understandable – just to stop writing. But the best way to fight your self-doubt is to keep writing. Even if you’re writing badly, it is much better than not writing at all – if you stop writing, then your inner critic has won, and that can’t be right! Just write something, anything and see what happens. Don’t overthink your writing and never look for perfection. Just write for the joy of writing and you’ll create something, however small, that is worthwhile and this increase both your confidence and enjoyment. And if you keep going, I promise you the self-doubt will pass - it will come back, of course, but take advantage of the times when you’re feeling more confident, and use these to help keep going through the tougher moments. How do you try to overcome self-doubt as a writer? Add a comment and join the conversation. I’ve always loved monsters. Scary or friendly, gigantic or tiny, ugly or beautiful, it doesn't matter - somehow monsters help make sense of the world. As a child, books such as The World of the Unknown: Monsters (a great primer for any child interested in monsters) and Mysteries, Monsters and Untold Secrets fed my fascination with supernatural and mythological creatures, a fascination that has stayed with me into adulthood. Monsters are a consistent element in my novels: the Tree of Life trilogy is peopled by a cast of monstrous beasts such as the giant Carnifex, the winged Kongamato and the dreaded Malign Sleeper, not to mention the Redeemers who haunt Elowen from the very start of the story. Likewise, dragons, the ogre-like Thyrs and the demon-dog Barghests threaten the heroes of my novel This Sacred Isle. Monsters appear in the stories of every culture on Earth – we have been plagued by werewolves, centaurs, trolls, ogres, sea monsters and many more. They can manifest our deepest fears –or our deepest wishes; who has not longed to see a fiery dragon racing across the sky? In many mythologies monsters symbolised functions and aspects of humanity or the natural world. Monsters filled unexplored lands – as humans looked at blank spaces on their maps, of the lands beyond their borders, their imaginations created a fantastical menagerie. For example, in medieval times travellers’ tales spoke of dog-headed men and creatures with neither neck nor head, but with a face set into the middle of their chests. There were Amazons, satyrs, mermaids, Manticores – all portrayed in medieval art and literature. The tradition portraying monsters in art continued – some powerful examples include Apollo and Python by J.M.W Turner, The Colossus by Francisco de Goya and the myriad of beings in The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch. And this has continued into our own times, with monsters regular features of our books, films, television and games. Monsters might frighten, amuse or entertain, but they remain a constant feature of our imaginations. In this post, I want to discuss three of my favourite monsters. Of course, choosing just three is very difficult but if I tried to write about all my favourite monsters, this post would be endless! Some honourable mentions must go to Dracula, Medusa, the Minotaur and of course Talos (the giant bronze automaton so brilliantly created for the film Jason and the Argonauts). Balrog - from The Lord of the Rings I’ve posted before about the influence J.R.R Tolkien has had upon my writing and how reading the Lord of the Rings for the first time had an enormous impact on me. Many strange beings – good and evil – populate Middle-earth, and one that always intrigued me most was the Balrog, who attacks the fellowship in the Mines of Moria in one of the most memorable scenes in the whole book. In the complex mythology of Middle-earth, Balrog were once Maia spirits who were corrupted by Melkor / Morgoth into his evil service. The Balrog who appears in The Fellowship of the Ring was buried deep underground, unearthed accidentally by the dwarves to haunt the dark halls of Khazad-dûm. Tolkien does not rush to reveal this terrible being – its presence is hinted long before its appearance. First the fellowship hears troubling sounds" ‘That was the sound of a hammer, or I have never heard one,’ said Gimli. ‘Yes,’ said Gandalf, ‘and I do not like it. It may have nothing to do with Peregrin’s foolish stone; but probably something has been disturbed that would have been better left quiet.’ And after their initial struggle with the Moria Orcs, Gandalf says: ‘Something dark as a cloud was blocking out all the light inside.’ All this tension would be wasted if the monster failed to match our fears, but here Tolkien succeeds. When the Balrog is finally seen, we truly see its strength, its horror. ‘Its streaming mane kindled, and blazed behind it. In its right hand was a blade like a stabbing tongue of fire; in its left it held a whip of many thongs.’ Tolkien tells us enough to inspire fear and awe, but leaves space for the reader to imagine the gruesome details of the Balrog – everyone who reads the Lord of the Rings is left with their own impression of this monster of fire and darkness. I feel it was telling that in the run-up of the release of Peter Jackson’s superb film adaptation of The Fellowship of the Ring, the appearance of the Balrog was one of the most discussed elements – fortunately, Jackson’s version did not disappoint (the heat haze when the Balrog roared was a stroke of genius), and was an undoubted highlight of the film, adding yet more awe and horror to Tolkien’s monstrous creation. Grendel from Beowulf Grendel appears in the great Anglo-Saxon epic poem Beowulf. Composed sometime between 680 and 800AD, it tells of the adventures of the Scandinavian hero Beowulf as he battles three terrifying supernatural enemies: the monster Grendel, Grendel’s mother and a mighty dragon. Beowulf comes to the aid of Hrothgar, King of the Skyldings in Denmark. Hrothgar’s great hall Heorot has been abandoned for twelve years, following attacks by the monster Grendel, who strikes at night, crushing warriors to pieces and dragging their corpses back to the marshy wilderness. Grendel is provoked by the sounds of feasting from Heorot: “Then the brutish demon who lived in darkness impatiently endured a time of frustration: day after day he heard the din of merry-making inside the hall, and the sound of the harp and the bard’s clear song.” Beowulf confronts Grendel, tearing off the monster’s right arm in a furious struggle – the mortally wounded Grendel flees, returning to his marshy home to die. After Beowulf faces and slays Grendel's avenging mother, he becomes King of the Geats and reigns for fifty years, until he dies defeating a dragon that ravages his kingdom. My first awareness of Grendel came as a child when reading The World of the Unknown: Monsters and I saw a vivid depiction of him – his anger, his rage, his madness. I first read Beowulf at school and have read different versions since – including Seamus Heaney’s wonderful translation – and always find new pleasure and meaning in the story. My novel This Sacred Isle was in no small part inspired by Beowulf and the hero’s battles with the three monsters, and I am sure there are countless interpretations of what the character of Grendel means, but for me, Grendel symbolises fear of the unknown, of the wild, one of the most primal of all human fears. We live in an increasingly urbanised and connected world, but the fear lingers that in the remaining wild spaces, monstrous horrors still lurk… The Pale Man from Pan's Labyrinth The Pale Man is a haunting, unsettling presence in Guillermo del Toro's masterpiece of fantasy cinema: Pan’s Labyrinth. The story takes place in Spain during the early Francoist period, five years after the bloody Spanish Civil War. Ofelia travels with her pregnant mother to live with her stepfather, Captain Vidal, who mercilessly hunts the Spanish Maquis who fight against the Francoist regime in the region. The narrative intertwines the brutal reality with a mythical underworld - Ofelia meets a faun who tells her she is the reincarnation of a lost princess of the underworld realm; the faun gives Ofelia a book and tells her she must complete three tasks to acquire immortality and return to her kingdom. During her second task, Ofelia encounters the Pale Man: a child-eating monster, he is a hideous, cadaverous figure with eyeballs in the palms of his hands. He sits alone and motionless at a lavish banquet, though the plates and bowls of food are untouched. Although Ofelia is warned not to eat anything there, she takes grapes, awakening the Pale Man. He chases Ofelia, but she manages – just - to escape his murderous clutches.

The cruelty of fascist Captain Vidal, the Francoist state and a complicit Catholic Church are all embodied within the Pale Man: like these oppressive powers, the Pale Man devours the young, endlessly, piteously, a nightmarish vision of madness and lust. Monsters often reflect our worst human excesses, and in doing so form a warning we would do well to heed. I believe the Pale Man is fascism stripped of all pretence and illusion, stripped of all the flags, the uniforms, the speeches, the propaganda – all that remains is cruelty and monstrosity. Which are your favourite monsters? Please leave a comment and join the conversation.

One of the joys of reading fantasy fiction is the opportunity to dive into and explore imaginary worlds. Well-crafted secondary worlds are not mere background – they enhance and enrich the story, and help shape the characters and themes. These worlds feel like living and breathing places, as if the author is using a real setting, describing lands and places they have actually visited. Such worlds seem to exist beyond the immediate narrative of the story; as a reader you can easily imagine other stories happening simultaneously, with other characters experiencing adventures and challenges of their own.

In this post I am going to discuss three of my favourite imaginary worlds – Middle-earth, Osten Ard and Gormenghast. Middle-earth I have posted previously about how the work of J.R.R Tolkien inspires my writing, and of all the secondary worlds in fantasy fiction, Middle-earth is the most famous and the most imitated, inspiring settings across the genre of epic fantasy. Tolkien described his world: “The theatre of my tale is this earth, the one in which we now live, but the historical period is imaginary. The action of the story takes place in the North-west of Middle-earth, equivalent in latitude to the coastline of Europe and the north shore of the Mediterranean.” Middle-earth is complex and coherent, drawn from deep pools of mythology, language, history and geography. Tolkien’s academic grounding in Anglo-Saxon, Celtic and Norse mythology helped shaped the landscape. The scale and depth of Tolkien’s creation is almost overwhelming: the characters, races, lands and legends. Readers have long pored over maps of Middle-earth, exploring places such as the peaceful, bucolic Shire, Rivendell, Gondor, Mirkwood and the bleak, desolate Mordor.

This is an ancient landscape, with a real sense of history; Middle-earth shows the effects of time, with the remnants of lost civilisations such as the Tower of Amon Sûl, the Barrow-downs and the Argonath. The natural world is always present – flora and fauna, the passing of the seasons, the night-sky, the sun and the moon. Despite the fantasy elements – the creatures, the sorcery – Middle-earth feels real and the characters endure real physical ordeals (hunger, thirst and exhaustion); the rules of nature are not ignored, and indeed serve to underpin and strengthen the fantastical parts of the story.

The story is deeply rooted in the landscape: Middle-earth is alive, an active character in Tolkien’s work. For example, when the Fellowship attempts the pass of Caradhras, they describe the mountain as though it was a character: Gimli looked up and shook his head. ‘Caradhras has not forgiven us,’ he said. ‘He has more snow yet to fling at us, if we go on. The sooner we go back and down the better.’ And think of the forests of Middle-earth, such as Fangorn, Mirkwood and the Old Forest – these are not generic woodlands but places with unique characteristics, and perils, of their own, and each serves to challenge the characters in Tolkien’s stories. This is not an inert landscape, just a passive resource to be plundered – Middle-earth reflects Tolkien’s profound ecological concerns and his respect, even reverence, for the natural world. And Middle-earth is a threatened world, whether through the malice of Sauron or from Saruman’s uncontrollable lust for technology and power. The words of Saruman retain a chilling resonance to our own world’s problems: "We can bide our time, we can keep our thoughts in our hearts, deploring maybe evils done by the way, but approving the high and ultimate purpose: Knowledge, Rule, Order; all the things that we have so far striven in vain to accomplish, hindered rather than helped by our weak or idle friends. There need not be, there would not be, any real change in our designs, only in our means." Saruman ruins his environment to serve his own purpose – he is indifferent to the damage he creates, he sees only his own needs and desires. In our world of growing man-made environmental catastrophe, this is something we can easily recognise. Tolkien’s work may have a reputation at times for being cosy and inward-looking, but he warns against the folly of unfettered greed and ambition, and shows that exploitation of our natural world can lead only to our own suffering, even destruction. Middle–earth forms part of the imaginative landscape of millions of readers, and continues to be an inspiration for writers, artists, filmmakers, musicians and environmentalists.

Osten Ard

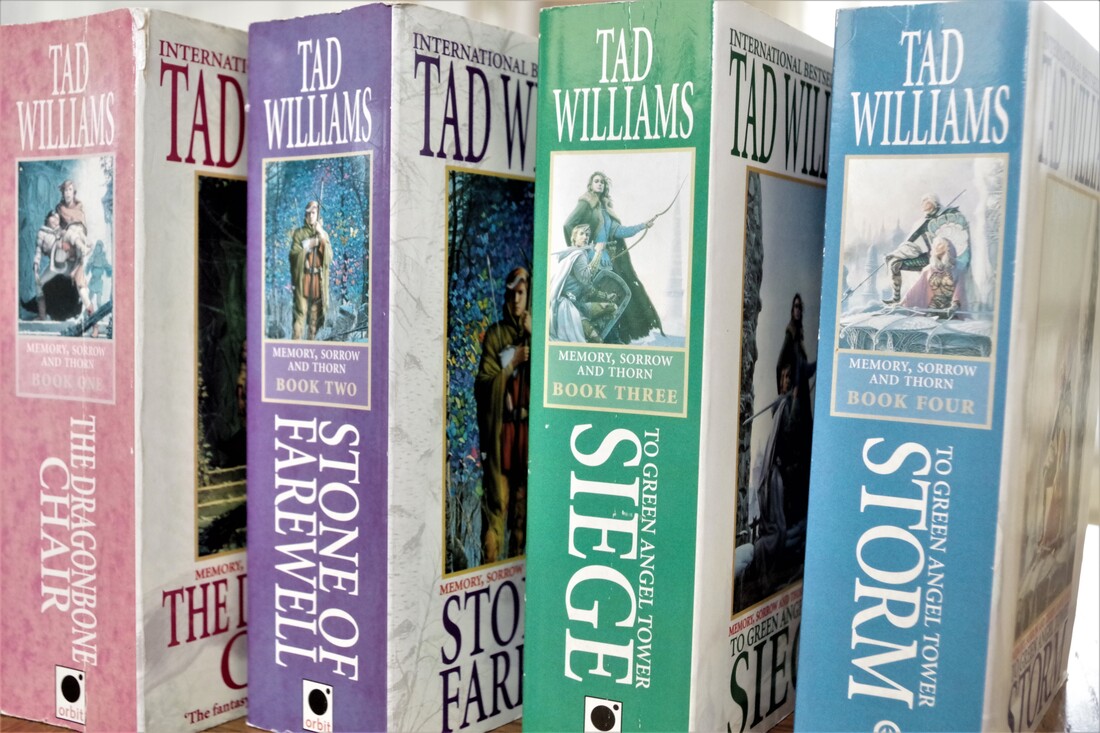

“Welcome stranger. The paths are treacherous today.” I first encountered the world of Osten Ard in Tad Williams’s landmark epic fantasy series Memory, Sorrow and Thorn – an influential work described by Locus magazine as ‘The fantasy equivalent of War and Peace.’ Superficially, Osten Ard resembles many Tolkien-inspired secondary worlds, with its medieval milieu, mountains, forests and swamps, but the Memory, Sorrow and Thorn series both uses and challenges many tropes and assumptions of the genre. There are few easy answers in Osten Ard, and do not expect simple separation into good and evil.

Memory, Sorrow and Thorn is a long read but never dry; written with wit, wisdom and intelligence, it is filled with excitement and memorable three-dimensional characters (Isgrimnur and Binabik are two of my favourites). And the world of Osten Ard – from the Wran to the Nornfells – plays an enormous role in the success of the story.

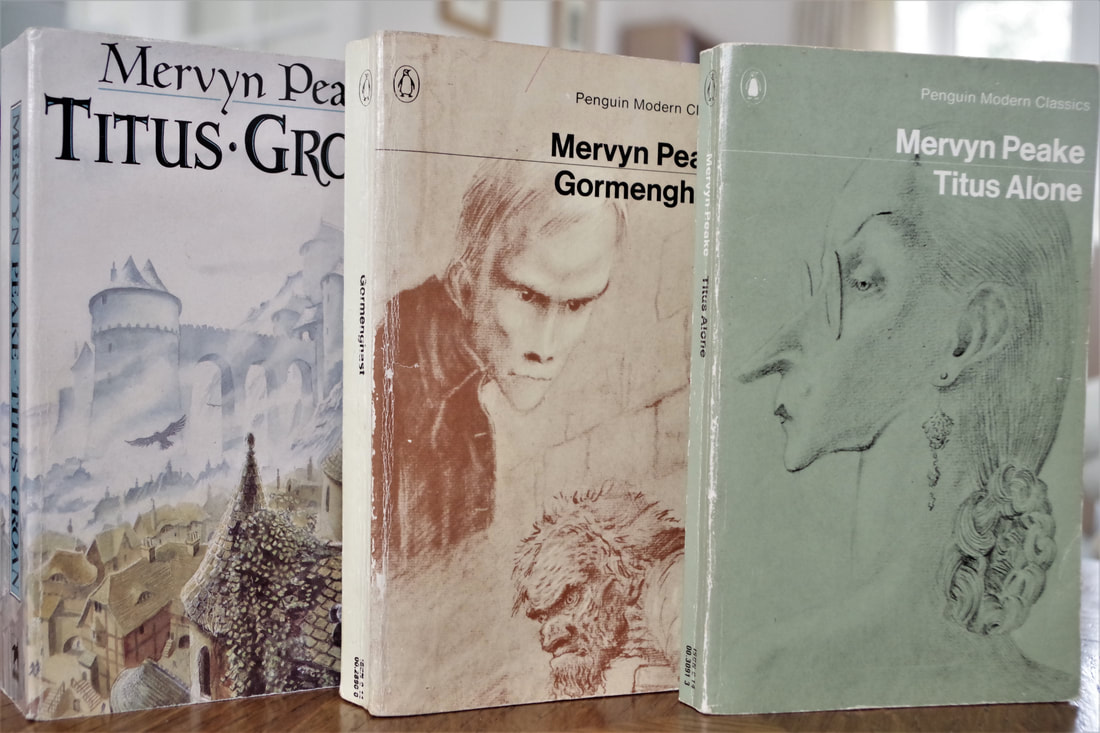

The depth and coherence of Osten Ard gives a strong foundation to the fantastical parts of the story, and in many cases reflects the psychology of the races and characters within. For me, the most fascinating part of Osten Ard is the fortress of the Hayholt. Doctor Morgenes describes it thus: “The Hayholt and its predecessors – the older citadels that lie buried beneath us – have stood here since the memories of mankind.” The Hayholt was formerly known as Asu'a, and was a city of the Sithi, the elf-like former rulers of Osten Ard, before it was besieged and captured by human invaders. The Hayholt is a haunted place, a place of secrets, with tunnels and caves beneath – it is not just a striking location, it symbolises suppressed human guilt over their genocidal war against the Sithi. This is typical of the complexity and ambiguity that lifts Osten Ard far above most secondary worlds in the genre. If you are yet to discover Memory, Sorrow and Thorn, then I recommend you make it your next fantasy read – the paths might be treacherous, but once you start exploring Osten Ard, you’ll find it a rewarding and absorbing journey. Gormenghast “Gormenghast, that is, the main massing of the original stone, taken by itself would have displayed a certain ponderous architectural quality were it possible to have ignored the circumstances of those mean dwellings that swarmed like an epidemic around its outer walls.” Sometimes lazily compared to the Lord of the Rings, Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast books (consisting of Titus Groan, Gormenghast and Titus Alone) resist easy description and classification: a fantasy, a scathing allegory of British life and society, a dystopian vision - whether the books are perhaps all these things or none, there can be no doubt they form a highly original work, dreamlike, layered and gothic. Central to the story is the monstrous edifice of Gormenghast itself; the ancient towers and mighty walls create a dense oppressive atmosphere, and an ideal setting for the madness of the ritual-ridden society trapped within. In less skilful hands, the dark architecture – the Stone Lanes, the Tower of Flints, the Great Kitchen – could have submerged the story, but instead through Peake’s witty prose, the setting adds elements both surreal and darkly comic.

The story is peopled by a carnival of eccentrics, such as the demonic cook Swelter, the cadaverous Mr Flay, Lord Sepulchrave (76th Earl of Groan), morose, exhausted, depressed by the endless demands of his role, and of course the murderous kitchen-boy Steerpike, the main driver of the narrative who schemes and slaughters his way to power. With life orchestrated by each day’s instructions from the Book of Ritual, many of the characters inhabit the dank, damp corridors and rooms of Gormenghast like ghosts. Yet, although the inhabitants of Gormenghast are larger than life, they have only too human foibles and failings such as greed, vanity and ambition. It is a fantasy but one uncomfortably close to our own lives; if we choose to look we can see our own weaknesses reflected.

Despite the eccentricities (though this is not a fantasy world of magic and dragons), Gormenghast feels so real, so tangible. When reading these books, I can almost smell the damp and mould, shiver in the cold rooms and passages, cower under the crumbling walls and towers of stone. Gormenghast itself, huge and malevolent, seems to be rotting, sinking, reflecting the corruption and empty ritual of its society. But while there is doubtless darkness in the Gormenghast books, a deep, suffocating darkness at times, one can also find kindness, humour, beauty and tragedy, all held together by Peake’s wit, psychological insight and vision. Which are your favourite fantasy worlds? Please leave a comment and join the conversation. If you’re interested in my writing, you can get the ebook version of my first novel - The Map of the Known World – for FREE. Please see the following Kindle preview: |

Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed