|

All authors draw on a wide range of inspirations when creating their stories, such as real-life experiences, places they have visited, concerns about the world and society, books they have read. For me, visual art has always inspired and influenced my writing. I cannot claim to be an expert in art history, and as much as I enjoy sketching my artistic skills are limited at best, but I find it an endlessly absorbing subject and a way of finding different perspectives on the world. By offering us a safe space to consider and explore feelings and fears we otherwise feel uncomfortable in confronting, art can help us all feel a little less alone in this world.

In this blog series, I am going to focus on four artists who have been particularly important to me and my creative work: Ian Miller, Elisabeth Frink, Paul Nash and Alfred Wallis. In this post, I am going to discuss the work of Paul Nash. Sometimes your appreciation of an artist develops over time – you slowly connect to their style, craft and symbolism. Other artists are like love at first sight: the first glimpse of a painting or sculpture creates an instant connection, an instant meaning. For me, Paul Nash is definitely in the latter category. Whether it’s the raw power of his First World War art, the melancholy of his Dymchurch paintings or the mythical energy of his abstract work inspired by the Avebury Stone Circle, I find his work endlessly fascinating, his symbols resonant and meaningful. I even named my small publishing company after Nash’s series of Monster Field photographs.

One of the most influential British artists of the twentieth century, Paul Nash demonstrated an intense relationship with landscape, never just recording the topography, not just recording what his eyes saw; instead he added deeply personal levels of symbolic meaning, giving the landscapes he portrayed an animated, vital presence.

Born in 1889, Nash’s early work was influenced by the Pre-Raphaelites and William Blake, and produced drawings and paintings of dream-like landscapes, often peopled with mysterious figures. In particular, Nash filled his trees with life, almost giving them personalities of their own: "O Dreaming trees,

As with millions across the world, Nash’s life changed with the outbreak of the First World War. He enlisted in the Artists’ Rifles in September 1914 and was stationed in England until deployed to the Ypres Salient in March 1917. This spell on the Western Front proved short-lived, as Nash suffered a non-combat injury and was invalided home. He returned to Belgium in October 1917 as an official war artist, depicting the shattered landscape.

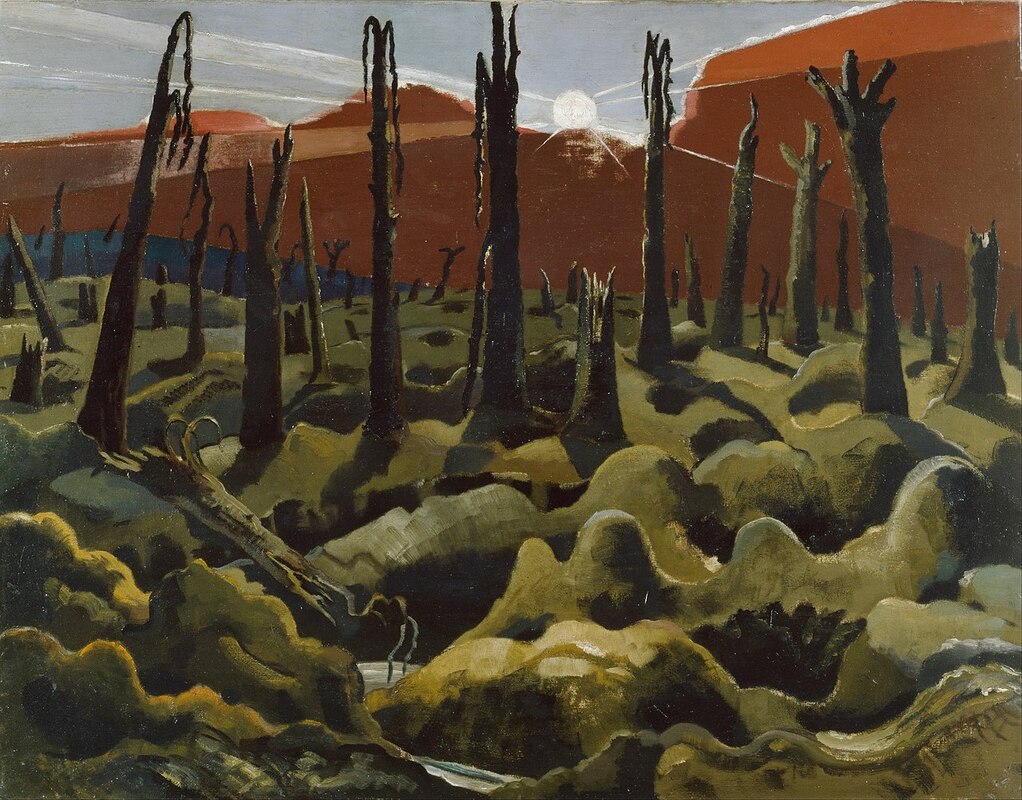

Not only did war change Nash’s life, it also transformed his art. Perhaps the most famous painting of Nash in this period is We Are Making A New World. This is a painting I had seen reproduced many times but I saw the original for the first time in an exhibition at the Imperial War Museum in London. Few paintings have had such an impact on me – the ravaged, brutalised landscape reflected not only the violence of war but Nash’s own emotional experience of the conflict. Sometimes I see this as a hopeful painting; other times I feel it is filled with despair. Look at the pallid sun peeking through the blood-red tide of clouds – is it striving to bring light and hope to the shattered world below, or is it too frightened to peer at the horror Mankind has inflicted?

After the war, Nash moved to Dymchurch in Kent, where he made a series of stark paintings of the sea and coastal defences. Nash, who had nearly drowned as a child, portrays the sea as menacing and cold – the harsh angles and blade-like waves are as threatening and desolate as No-Man’s Land, the grim memories of war spilling over Nash’s work even in peacetime. To me, the paintings evoke a sense of emptiness, of loss and depression.

The Dymchurch paintings show again Nash’s connection to landscape, and it is this connection that has most influenced me as a writer. For example, when writing my novel This Sacred Isle, Nash’s symbolic landscapes remained at the forefront of my thinking. I wanted to present the landscape of that story as liminal and to show traces of the history it had witnessed, where there exist forces and influences beyond what is normally visible. To quote Nash:

"The landscapes I have in mind are not part of the unseen world in a psychic sense, nor are they part of the Unconscious. They belong to the world that lies, visibly, about us. They are unseen merely because they are not perceived."

Paul Nash had a powerful emotional attachment to places such as Avebury, which he said possessed a quality he called the genius loci.

This sense of places having its own 'character' or 'spirit' was something I tried to create within This Sacred Isle, for example, in the scene Morcar meets the Stag Lord, a scene that plays out in a dreamlike, symbol-laden landscape. A quote from Paul Nash captures the feeling I was trying to achieve: "The divisions we may hold between night and day - waking world and that of dream, reality and the other thing, do not hold. They are penetrable, they are porous, translucent, transparent; in a word they are not there."

Nash’s connection with Avebury inspired me to visit the stone circle, and once there I could understand why it held such a fascination for the artist – combined with the surrounding landscape, encompassing sites such as Silbury Hill and West Kennet, it forms such an evocative place, steeped in history and myth. Avebury is an important location in my next novel, Second Sun, and this is in no small part due to the influence of Paul Nash – for me, and I’m sure many other people, his work will remain an ongoing inspiration.

Part 1 - Ian Miller

Part 2 - Alfred Wallis Part 3 - Elisabeth Frink If you’re interested in my writing, you can get the ebook version of my first novel - The Map of the Known World – for FREE. Please see the following Kindle preview:

3 Comments

11/1/2023 03:25:42 pm

Post is very useful.Thank you this usefull information.

Reply

11/1/2023 04:27:37 pm

You slowly connect to their style, craft and symbolism. Other artists are like love at first sight: the first glimpse of a painting or sculpture creates an instant connection, an instant meaning. Thank you for taking the time to write a great post!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed