|

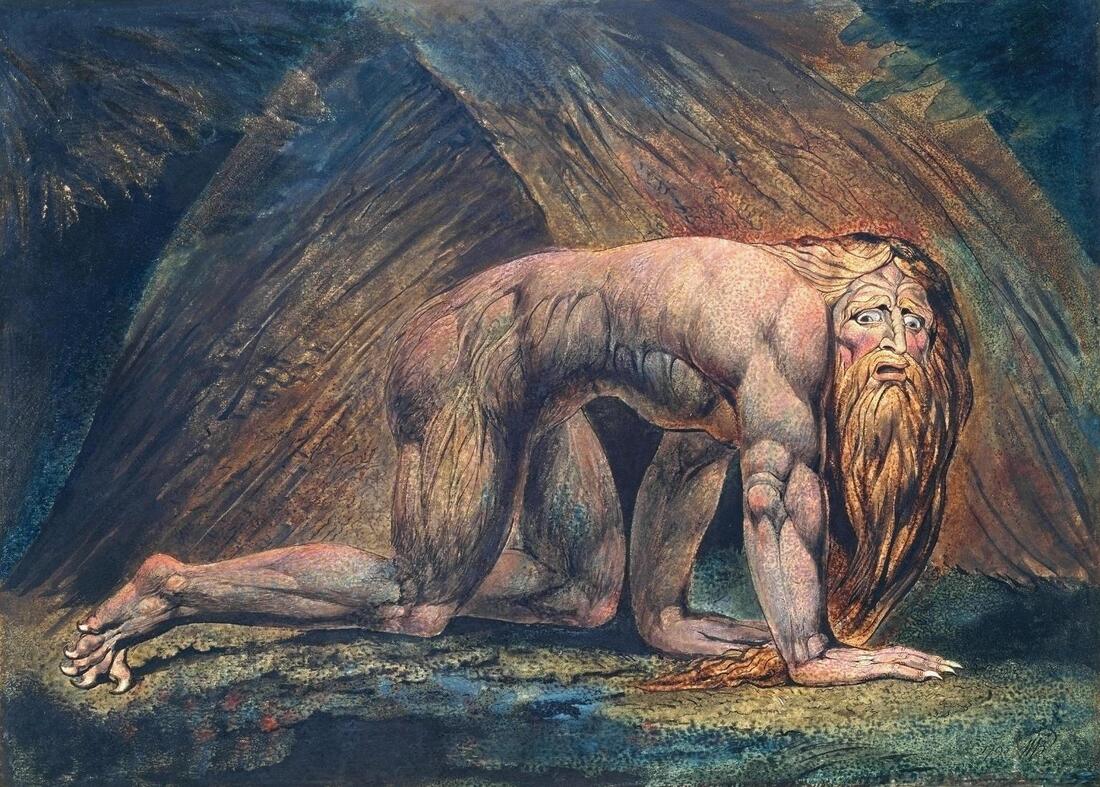

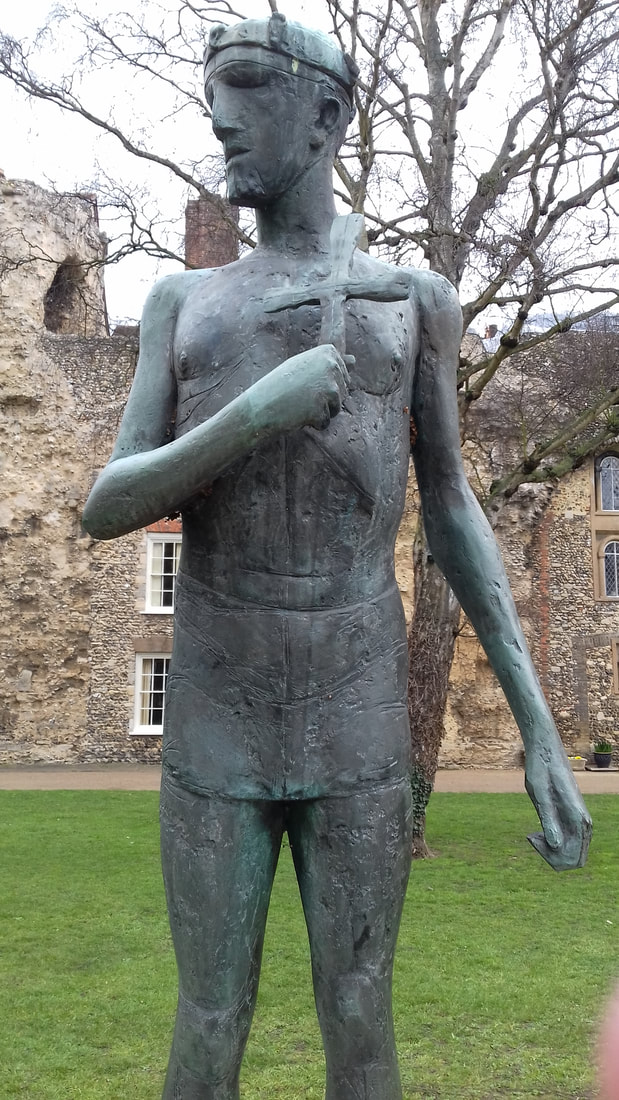

Like any author, I draw upon a broad range of inspirations when writing a book, and for me, visual art has always informed and influenced my writing. Although far from blessed in my drawing and painting skills, I’m rarely happier than when wandering around an art gallery! In this blog post, I am going to focus on four artists who have been particularly important and inspiring to me when I was working on my new novel The Waste. William Blake I have long been fascinated by the work of visionary painter and poet William Blake (1757-1827). His art is both highly personal and highly original, infused with his rebellious spirit and enormous imagination. Encompassing biblical and mythological themes, the delicate strangeness of Blake’s work is powerful and seeing the collection of his work is always a highlight of any visit to the Tate Britain. Through his art and prophetic books, Blake developed a very personal mythology with a host of symbolic characters, and this mythology, along with the graceful, idealised human figures in Blake’s art, was a significant influence for me when writing The Waste, especially when developing the characteristics of the alien Seraphim. The act of developing and writing a novel can be a hard slog, but to spend time researching and thinking about Blake’s art and writings was a pleasure in itself. Paul Nash If I have such a thing as a favourite artist, then I think it would be Paul Nash (1889-1946). Whether it’s the raw, uncompromising power of his First World War art, the melancholy of his Dymchurch paintings or the mythical energy of his work inspired by the Avebury stone circle, I find his work captivating, his symbols resonant and meaningful. Perhaps Nash’s best-known work is We Are Making A New World. I saw the original for the first time in an exhibition at the Imperial War Museum in London. Few paintings have had such an impact on me – the battle-ravaged, brutalised landscape reflected not only the hideous violence of war but Nash’s own emotional experience of the conflict. Consider the pallid sun peeking through the blood-red tide of clouds – is it striving to bring light and hope to the shattered world below, or is it too frightened to peer at the horror Mankind has inflicted? This painting makes an appearance in The Waste and Spare’s experience of viewing it certainly echoes my own. Through his paintings Paul Nash demonstrated an intense relationship with landscape, not just recording what his eyes saw, but adding deeply personal levels of symbolic meaning, giving the landscapes he portrayed an animated, vital presence. From his early drawings and paintings, influenced by Samuel Palmer and William Blake, to the harsh angles and blade-like waves of his Dymchurch work, which evoke such a sense of emptiness, of loss and depression, the landscapes of Nash are alive and mythic. This sense of place, the genius loci, as Nash referred to it when he described places such as Avebury, was something I wanted to reflect within my novel. The titular Waste of the book is both a literal and symbolic landscape, where the layers of human history are almost a tangible presence. I have no doubt Paul Nash will remain a primary inspiration for my writing. Dame Elisabeth Frink My first, very striking, encounter with the work of Dame Elisabeth Frink (1930-1993) took place in Bury St Edmunds in my home county of Suffolk. In the grounds of St Edmundsbury Cathedral stands a bronze statue of Edmund, a ninth century king of East Anglia. After being defeated in battle by the Great Viking army, it is said Edmund refused his enemies’ demand to renounce Christ and so was beaten, shot through with arrows and beheaded. Legend tells the Vikings threw Edmund’s severed head into the forest, but it was soon retrieved by those loyal to the king when they followed the cries of a mysterious wolf. Frink’s statue shows King Edmund as a young man, a cross grasped in his hand. This is not a caricature of a warrior or a king – there is pride in Edmund’s face but a sense of vulnerability, his slender body is fragile. Frink’s Edmund is very much a king, a saint, and a martyr, but still a human being. This often-unsettling combination of history, myth and human frailty seems to be present throughout much of Frink’s art. During the writing of The Waste, I was especially interested by Frink’s goggle head sculptures; shaped by Frink’s interest in themes of masculine aggression, the goggle heads’ sense of faceless authority very much shaped the look and attitude of the Shades, the cold, impersonal, unaccountable police force of my novel. The goggle head sculptures avoid eye contact, concealed behind polished headgear – they are dehumanised and as such offer a threat that cannot be reasoned with. The Shades in The Waste are human, but just as their visors hide their human faces, their humanity is also hidden and they appear almost machine-like, robotic. The unsettling and enigmatic nature of Elisabeth Frink's art continues to be both fascinating and inspiring. Alfred Wallis Alfred Wallis (1855 - 1942) produced profoundly personal art, painting images of ships, boats, Cornish villages and the sea. With no formal art training, Wallis only took up painting after his wife’s death – with little money for materials, he mostly painted on found pieces of cardboard. Wallis painted from memory, drawing on his sea-faring experiences, to capture a rapidly disappearing way of life. Wallis’s limited palette and distorted perspective give his work a distinctive look. Within his paintings, Wallis played with size and scale of objects, and although the paint is roughly applied, he often achieved high levels of detail. Wallis’s instinctive compositions give his paintings real vitality – you can almost taste the briny air, hear the waves booming. The art of Alfred Wallis, and discovering more about his life, unlocked for me the character of ‘The Captain’ in The Waste, who although is not meant to represent the real Wallis, does share many of the same motivations and obsessions. It is important not to romanticise the life of Alfred Wallis – he struggled with poverty and, it would appear, mental health difficulties – but he brought something profound and original into the world, and I hope he gained pleasure from the creation of his art.

The Waste is out now, available in eBook and paperback, and free to read through Kindle Unlimited.

0 Comments

Landscape, and a sense of place, has always been important in my writing and my new science fiction dystopian novel The Waste is no exception. The novel moves through London, Gippeswic (an alternate version of Ipswich in Suffolk) to the Waste, which is a massive open-air prison covering a large swathe of south-western England. In this blog post, I will cover some of the real-world locations that helped inspire my novel. London Parts of the novel take place in (a much changed) City of London, with buildings such as the Shard, Saint Paul’s Cathedral, Saint Mary Woolnoth church and Liverpool Street Station appearing in thinly veiled forms. This is an area of London steeped in history, which I always find fascinating and enjoy walking around (especially when quieter at the weekends) and it formed an interesting backdrop to parts of the story. Within the novel, these flashes of history also contrast with the society the Seraphim are encouraging humans to build: a society focused only on the present, only on personal gain and pleasure. The inclusion of Saint Mary Woolnoth church is also a nod to The Wasteland by TS Eliot, which inspired some of the imagery in the novel. Avebury World Heritage site The area around Avebury in Wiltshire contains an extraordinary cluster of monuments dating to the Neolithic and Bronze Age, including the famous Avebury Stone circle, Silbury Hill and West Kennet Long Barrow. Having been fortunate enough to visit this area on a few occasions, it is difficult to put into words the atmosphere this landscape exudes. As you walk around the henge and stone circle at Avebury, or face the imposing mass of Silbury Hill, or walk up to the mysterious West Kennet Long Barrow, there is a sense of deep time, of landscape shaped by countless layers of human history. From the earliest stages of writing The Waste, Avebury and the surrounding area always formed a key location in the story. In the book, the henge and stone circle at Avebury appears as Havock, the chief settlement of the dreaded Mohock clan, while Silbury Hill emerges in grisly fashion as their chosen place for executions. West Kennet Long Barrow also has a fleeting but important appearance. One of the reasons Avebury interested me in the first place was the work of artist Paul Nash, who has long been one of my favourite artists. Nash had a profound sense of landscape, with a powerful emotional attachment to certain places such as Avebury and Dymchurch, places which possessed a quality he referred to as the genius loci. Although the Waste is a prison, and a dangerous and savage place, it is also less touched and polluted by the modern world – as well as being at times horrifying, I wanted the Waste to be a dreamlike landscape, rich with a sense of history and symbolism. I believe this quote from Paul Nash encapsulates the sense of what I was reaching for:

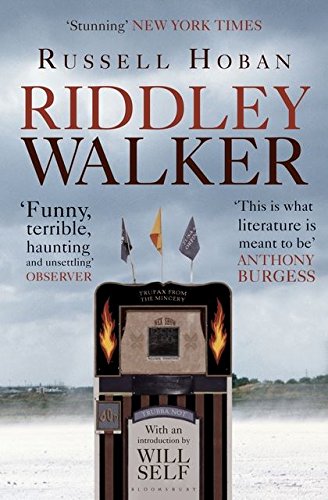

"The divisions we may hold between night and day - waking world and that of dream, reality and the other thing, do not hold. They are penetrable, they are porous, translucent, transparent; in a word they are not there." 'Dreams', undated typescript, Tate Archive The settings in The Waste are key elements in the novel, both challenging and revealing the characters, and although this is science fiction, they help achieve a sense of reality and history. The Waste is out now, available in eBook and paperback, and free to read through Kindle Unlimited. Image of St Paul's Cathedral by Raygee78 from Pixabay “On my naming day when I come 12 I gone front spear and kilt a wyld board he parbly ben the las wyld pig on the Bundel Downs any how there hadnt ben none for a long time befor him nor I aint looking to see none agen.” Just from this quote – the opening words of the novel – you will see Riddley Walker is a book unlike any other. The novel is set hundreds of years in the future, long after a nuclear holocaust, with England reduced to effectively an Iron Age level of existence. When his father dies in an accident, young Riddley Walker inherits a shamanistic role among his people, and when he uncovers an attempt to recreate the weapons that once devastated civilization, he is forced to go on the run. Twelve years’ old, though perceptive beyond his tender years, Walker narrates his adventure in the fragmented, fractured Riddleyspeak, a language as broken as the society portrayed in the story. I found Riddleyspeak a challenge, especially in the early pages, but in time (and with the help of a glossary at the end of the book), I began to adapt to the rhythm and structure. You are forced to slow your reading, and if anything, I think the book would benefit from being read aloud.

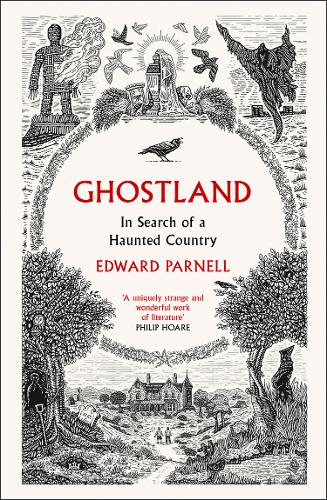

The language reinforces the sense we are seeing Riddley’s post-apocalyptic world through his eyes, adding to the force and energy of his descriptions. Hoban’s invented language fizzes with clever word-play, and through this we see echoes of the past, and adds to the sense shared by Riddley and other characters in the story of the heights civilization once reached, and the bitterness and sense of shame that all was lost through human aggression and greedy misuse of their technological wonders. The language can, in places, be very funny, for example in the twisted Kent placenames (Do-it-over = Dover, Horny Boy = Herne Bay) and the scene where Goodparley and Riddley attempt to interpret The Legend of Saint Eustace (written as it is in modern English). Riddley’s adventurous journey allows Hoban to build a grim portrayal of this ruined England, from the mysterious Eusa folk, the ruined cathedral in Cambry (Canterbury), the wandering packs of wild dogs and the Eusa Show, performed by the ‘Pry Mincer’ and the ‘Wes Mincer’, who on their travelling puppet shows perform allegorical propaganda stories to the , communities. It is an uncompromising vision, and as bleak and well-conceived a dystopia as I have ever encountered. Infused with mythological, folkloric and religious symbolism, Riddley Walker is rich for endless interpretation; it is not an easy read, but it is worth the effort – Trubba not. I would also add the edition of Riddley Walker I read had an entertaining introduction by novelist Will Self, which provided some valuable insights and context. If you spend any time in the lonely places of the British countryside – the deserted beaches, the dense forests, the Fens, the hills and mountains, the still ponds and lakes, the ruins half-swallowed by time – then you’ll be familiar with the occasional fleeting sense of there being something just out of sight, just out of hearing, a sense of watchfulness, of secrets and trauma long-hidden. It is these wild places, and the effect they have on us, that Edward Parnell explores in his outstanding book Ghostland – In search of a Haunted Country. In the best way, Ghostland is a difficult work to categorize. It is a book of haunted landscapes and haunted lives, a book filled with folklore, natural history, psychogeography and cinematic and literary references, all underpinned by the author’s deeply moving personal story. Whether exploring the crumbling cliffs and lonely beaches of Suffolk, or the sprawling Glasgow Necropolis, or the rugged coast and Neolithic moorlands of West Cornwall, and many locations in between, Parnell invokes a powerful sense of place and the stories and ghosts that surround and infuse them. Ghostland shines a light on some of Britain’s finest writers of horror and the uncanny, such as M.R. James, William Hope Hodgson, Arthur Machen and Alan Garner, showing how their obsessions and fears, and connections to their landscape, shaped their creations, often in unsettling ways. Although some of the authors mentioned in the book I am familiar with, there are others whose work I didn’t know, so one of the joys of Ghostland is discovering a list of novels and short stories I now can’t wait to read.

As well as ghostly literary tales, on-screen horrors are explored too, and not just folklore-inflected cinema and television such as The Wicker Man, The Children of the Stones and Jonathan Miller’s peerless M.R. James adaptation Whistle and I’ll Come To You (still an intense, disturbing experience), but also the dark strain of British public information films, which are vividly remembered, most likely in our personal and collective nightmares, by the generation exposed to them. For example, Lonely Water, a nightmarish warning of the perils of swimming in dangerous places (narrated with spine-tingling relish by Donald Pleasance), and Apaches, a terrifying short film I remember being shown at primary school – if the aim of Apaches had been to convince children growing up in rural Britain in the 1970s and 1980s that the countryside was filled with hidden and gruesome threats, then, from my perspective at least, it succeeded… I think anyone reading this book will find some moments of connection and resonance, whether in Parnell’s deep love and reverence for the natural world, his fascination with stories of the uncanny or in his sensitive but unflinching description of his own personal tragedies. For me, Ghostland demonstrates how our cherished places and stories – in any form – can help us manage and make sense of our real-life struggles. The best ghost stories don’t just frighten or excite us, they help to remind us to acknowledge painful memories – our own ghosts of the past – to help us move forward, to help us keep going, even when stricken with loss and grief. From the first page of Ghostland to the last, I fell under its haunted spell; I have no doubt it is a book I will revisit and reread, and I am sure every time I open it, I will find new treasures – and new horrors – buried within its pages. |

Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed