|

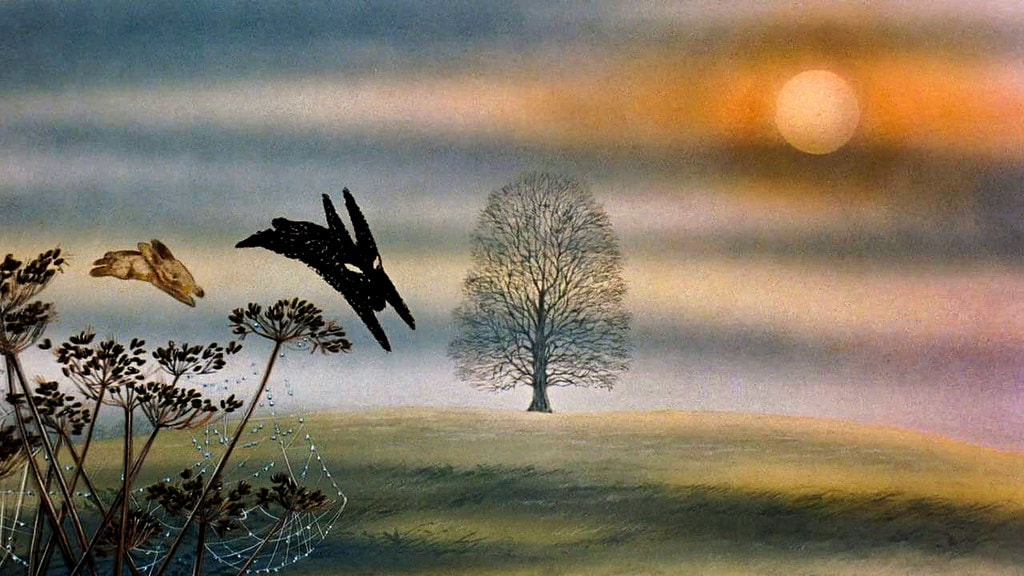

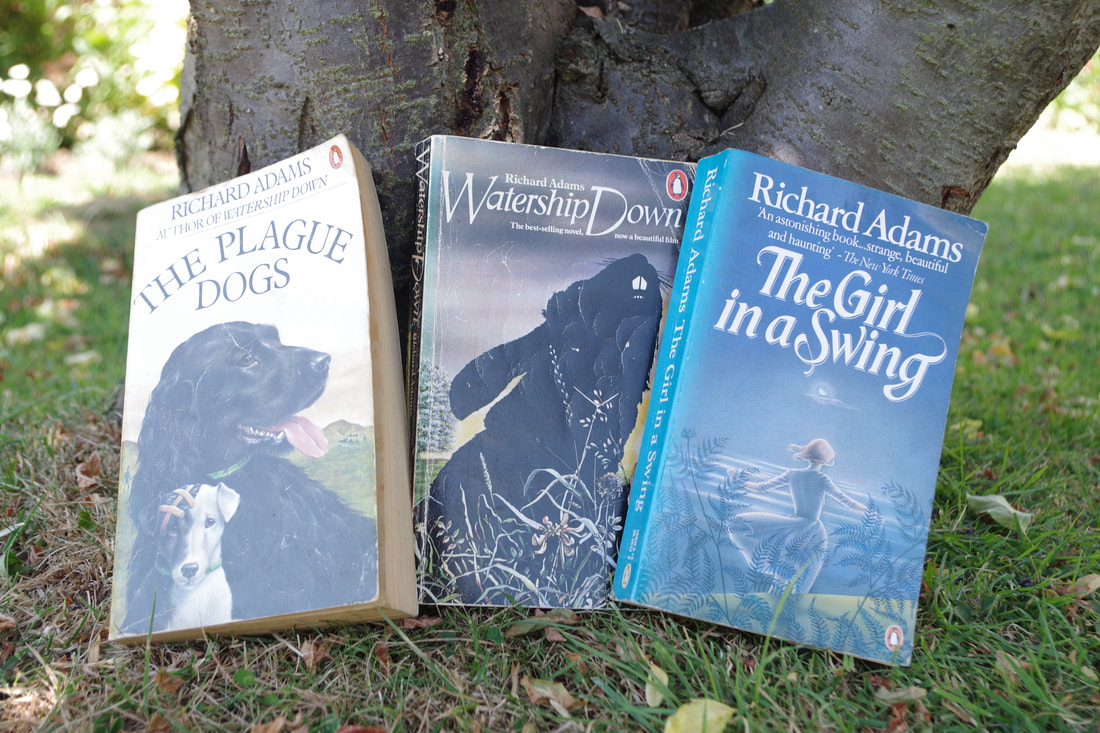

There are some books that stay with you throughout your life, books you first read as a child that shape your interests, even your worldview. For me, one of those books is Watership Down by Richard Adams. My introduction to Watership Down was through Martin Rosen’s 1978 film version – my dad took me see it at the (long-closed) ABC cinema in Ipswich and although too young to fully understand the story, the visuals left an indelible mark. I didn’t find the (now much-discussed) violence of the film unsettling; I just thought it was magical and extremely exciting. When a little older I finally read the book and it was one of the reading experiences that one only seems to have in childhood – long hours reading, no distractions, no sense of the world outside. I soon discovered that as thrilling as the film had been, the novel contained a far deeper, darker and even more satisfying story. Although the story takes place across just a few miles of English countryside, it is an epic adventure, and I found myself lost in the saga, fascinated by characters such as Hazel, Fiver, Bigwig and the terrible General Woundwort. When I first started writing short stories and novels, Watership Down remained one of those touchstones I returned to for inspiration, for encouragement. Indeed, the Isle of Ictis scene in my first novel, The Map of the Known World, was heavily influenced (in atmosphere and – in many ways – narrative function) by the creepy, disturbing sequence in Cowslip’s warren. I have longed admired the richness of Adams’s descriptive writing – the landscape of Watership Down, described of course from a rabbit’s eye view, is beautifully evoked, from the colours and scents of flowers, to the sinister buildings and machines built by humans. This sense of the landscape being intrinsic to a story is something I have carried through all my work, and in my novels such as This Sacred Isle, I have consciously tried to evoke the land as almost a character in itself, a character that influences and responds to the events of the story. Watership Down is not a direct allegory such as Animal Farm (another favourite book of mine) but through its themes, it offers strong comments on our world. For example, when I re-read the book as an adult, Adams’s interest in justice, specifically just leadership became clear through is treatment of the four warrens we visit during the story. Sandleford Warren is hierarchical, entrenched in its own rules; its chief, although wise and experienced, has largely withdrawn from contact with the world around him, and thus ultimately fails to understand or appreciate the seriousness of the threat facing the warren. He fails to act, condemning all, with the exception of Hazel and his friends, to extermination. As we move through the story, we come to Cowslip’s warren, where the inhabitants have effectively been tamed, and depend on the food supplied by the farmer, though with the knowledge that their life or relative ease means that regularly one or more of their kind will be caught within the snares. They are strictly not a community – they live almost individual lives, resigned to their fate, caring little for others. General Woundwort’s warren, the dreaded Efrafa is even worse – a tyrannical warren, where fear rules and any disobedience is punished by wounding or death. Only when the final warren is established on Watership Down is a just leadership achieved; the community is led by one who has earned the right to lead, not through power or fear or deviousness, but by intelligence, compassion and selfless actions. Perhaps Adams is reminding us to choose our leaders carefully – a lesson we would do well to heed… Adams clearly also had a profound understanding and knowledge of mythology and folklore. He makes references to classical mythology and literature in the novel, and was influenced by Joseph Campbell’s Hero of a Thousand Faces. The tales of trickster El-ahrairah have an authenticity, a heft, as though they are truly stories passed down and shaped by countless generations, as powerful guides to society, to life and death. And these stories are not just added to Watership Down to add colour and texture; although entertaining tales in their own right, they are not just entertainment. The adventures of El-ahrairah inspire and influence decisions and actions taken by characters in the book. In many ways, I believe Watership Down is a story about the power of story, the necessity of story in our lives – El-ahrairah gives meaning to the rabbits, an identity, connecting them to their past and encapsulating shared experiences across their species. One of the elements that separates Hazel and his companions from Cowslip’s warren is the latter’s rejection of the tales of El-ahrairah, a rejection of what unites their kind, a rejection of the lessons and hardships of the past, and a focus solely on the present: ‘Well, we don’t tell the old stories very much,’ said Cowslip. ‘Our stories and poems are mostly about our own lives here…’ Adams asserts that we all need stories – religious or otherwise – to make sense of our existence and to understand and connect with others. The power of story gives strength, energy and hope to Hazel and his companions, even in the darkest times; this contrasts to the stasis and imprisonment of Cowslip’s warren, where they have cast aside their freedom for a life of relative ease, and care little for each other, as Cowslip says: ‘Rabbits need dignity and above all, the will to accept their fate.’ Hazel, Fiver, Bigwig and the other rabbits escaping from Sandleford Warren refuse to accept their fate – they know their journey places them in danger, appalling danger, and that their chances of success are slim, but they have learned, partly through the tales of El-ahrairah, that to have any chance of survival, they need to act, to use their wits and to work with each other as a community. The impact of humanity on the natural world forms one of the most powerful themes in the novel. Throughout the book, we see the damage caused by humans, often through sheer indifference:

‘It comes from men. All other elil do what they have to do and Frith moves them as he moves us. They live on the earth and they need food. Men will never rest till they’ve spoiled the earth and destroyed the animals.’ The location of Sandleford Warren is starkly described as ‘SIX ACRES OF EXCELLENT BUILDING LAND’, nature reduced to a commodity, a resource. The warren is not destroyed deliberately or even out of malice – the rabbits’ existence is simply an irrelevance, their lives deemed worthless against the needs of humans. This was something that clearly troubled Richard Adams, who valued the natural world and the rights of non-human species. And it is not difficult to see how the creeping danger and damage of urbanisation Adams attacked are being realised in the real world. The fields and meadows around the English village in which I live are gradually disappearing beneath concrete and brick, any ecological concerns brushed away – what has been lost can never be recovered. Our ecology is irrevocably damaged by such relentless ‘development’, and as I believe Adams felt, our society is damaged too. Watership Down asks us to notice the world around us, the world around our feet, to see the beauty, the complexity, the richness of animal and plant life – only by seeing, only by understanding, will we value the natural world enough to take steps to protect it. I am sure Watership Down inspired many people to draw, to compose music, to write (I count myself in the latter) but I wonder how many people it inspired – and still inspires – to become environmental campaigners, or work to support animal rights? Watership Down is a book that can help us view the world in a more balanced, compassionate way - it is testament to the strange, sheer power of story that a tale of a small group of rabbits travelling through the English countryside can teach us valuable lessons about our lives too.

1 Comment

|

Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed