|

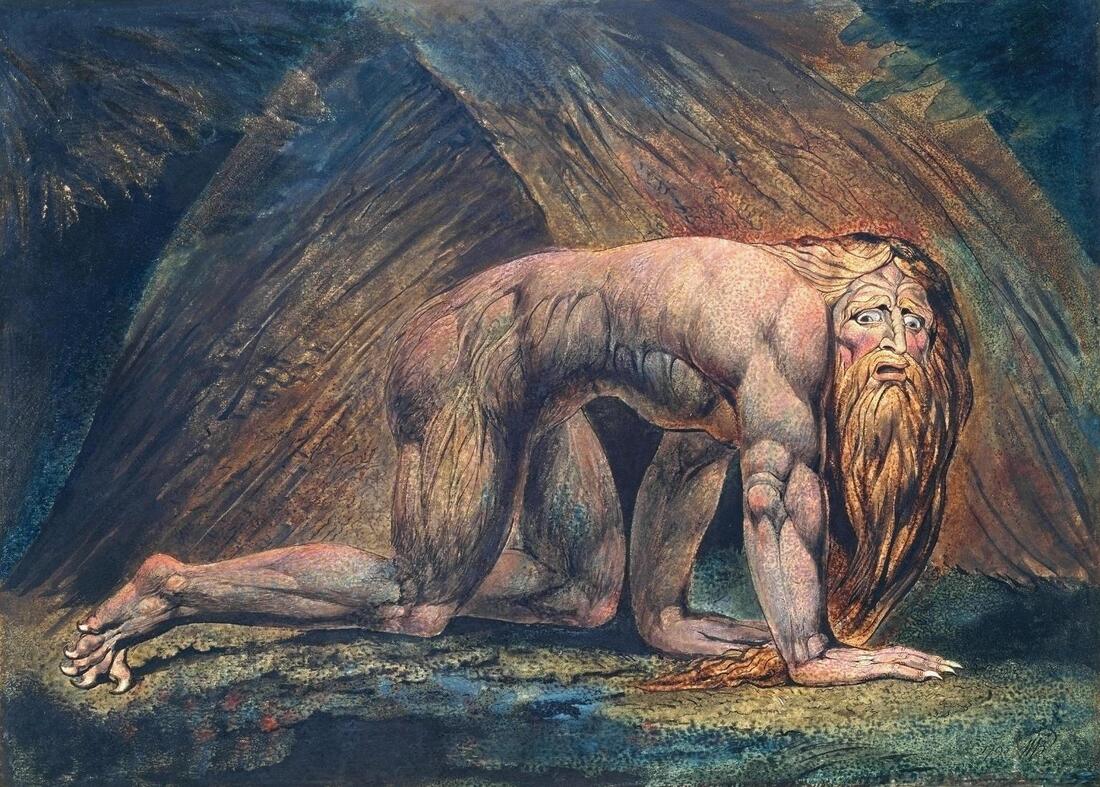

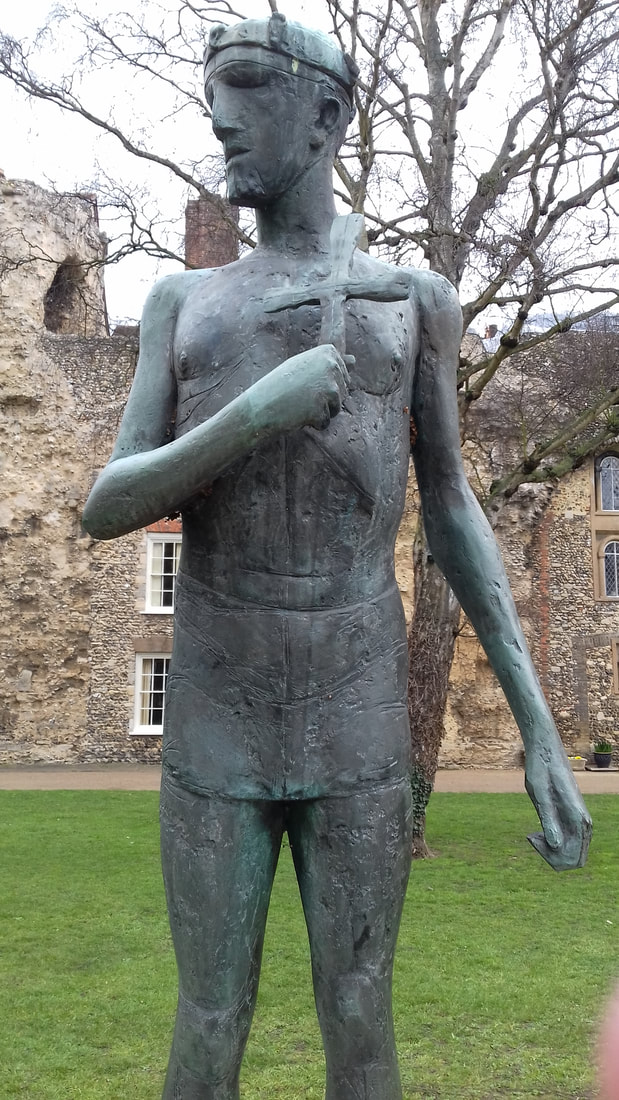

Like any author, I draw upon a broad range of inspirations when writing a book, and for me, visual art has always informed and influenced my writing. Although far from blessed in my drawing and painting skills, I’m rarely happier than when wandering around an art gallery! In this blog post, I am going to focus on four artists who have been particularly important and inspiring to me when I was working on my new novel The Waste. William Blake I have long been fascinated by the work of visionary painter and poet William Blake (1757-1827). His art is both highly personal and highly original, infused with his rebellious spirit and enormous imagination. Encompassing biblical and mythological themes, the delicate strangeness of Blake’s work is powerful and seeing the collection of his work is always a highlight of any visit to the Tate Britain. Through his art and prophetic books, Blake developed a very personal mythology with a host of symbolic characters, and this mythology, along with the graceful, idealised human figures in Blake’s art, was a significant influence for me when writing The Waste, especially when developing the characteristics of the alien Seraphim. The act of developing and writing a novel can be a hard slog, but to spend time researching and thinking about Blake’s art and writings was a pleasure in itself. Paul Nash If I have such a thing as a favourite artist, then I think it would be Paul Nash (1889-1946). Whether it’s the raw, uncompromising power of his First World War art, the melancholy of his Dymchurch paintings or the mythical energy of his work inspired by the Avebury stone circle, I find his work captivating, his symbols resonant and meaningful. Perhaps Nash’s best-known work is We Are Making A New World. I saw the original for the first time in an exhibition at the Imperial War Museum in London. Few paintings have had such an impact on me – the battle-ravaged, brutalised landscape reflected not only the hideous violence of war but Nash’s own emotional experience of the conflict. Consider the pallid sun peeking through the blood-red tide of clouds – is it striving to bring light and hope to the shattered world below, or is it too frightened to peer at the horror Mankind has inflicted? This painting makes an appearance in The Waste and Spare’s experience of viewing it certainly echoes my own. Through his paintings Paul Nash demonstrated an intense relationship with landscape, not just recording what his eyes saw, but adding deeply personal levels of symbolic meaning, giving the landscapes he portrayed an animated, vital presence. From his early drawings and paintings, influenced by Samuel Palmer and William Blake, to the harsh angles and blade-like waves of his Dymchurch work, which evoke such a sense of emptiness, of loss and depression, the landscapes of Nash are alive and mythic. This sense of place, the genius loci, as Nash referred to it when he described places such as Avebury, was something I wanted to reflect within my novel. The titular Waste of the book is both a literal and symbolic landscape, where the layers of human history are almost a tangible presence. I have no doubt Paul Nash will remain a primary inspiration for my writing. Dame Elisabeth Frink My first, very striking, encounter with the work of Dame Elisabeth Frink (1930-1993) took place in Bury St Edmunds in my home county of Suffolk. In the grounds of St Edmundsbury Cathedral stands a bronze statue of Edmund, a ninth century king of East Anglia. After being defeated in battle by the Great Viking army, it is said Edmund refused his enemies’ demand to renounce Christ and so was beaten, shot through with arrows and beheaded. Legend tells the Vikings threw Edmund’s severed head into the forest, but it was soon retrieved by those loyal to the king when they followed the cries of a mysterious wolf. Frink’s statue shows King Edmund as a young man, a cross grasped in his hand. This is not a caricature of a warrior or a king – there is pride in Edmund’s face but a sense of vulnerability, his slender body is fragile. Frink’s Edmund is very much a king, a saint, and a martyr, but still a human being. This often-unsettling combination of history, myth and human frailty seems to be present throughout much of Frink’s art. During the writing of The Waste, I was especially interested by Frink’s goggle head sculptures; shaped by Frink’s interest in themes of masculine aggression, the goggle heads’ sense of faceless authority very much shaped the look and attitude of the Shades, the cold, impersonal, unaccountable police force of my novel. The goggle head sculptures avoid eye contact, concealed behind polished headgear – they are dehumanised and as such offer a threat that cannot be reasoned with. The Shades in The Waste are human, but just as their visors hide their human faces, their humanity is also hidden and they appear almost machine-like, robotic. The unsettling and enigmatic nature of Elisabeth Frink's art continues to be both fascinating and inspiring. Alfred Wallis Alfred Wallis (1855 - 1942) produced profoundly personal art, painting images of ships, boats, Cornish villages and the sea. With no formal art training, Wallis only took up painting after his wife’s death – with little money for materials, he mostly painted on found pieces of cardboard. Wallis painted from memory, drawing on his sea-faring experiences, to capture a rapidly disappearing way of life. Wallis’s limited palette and distorted perspective give his work a distinctive look. Within his paintings, Wallis played with size and scale of objects, and although the paint is roughly applied, he often achieved high levels of detail. Wallis’s instinctive compositions give his paintings real vitality – you can almost taste the briny air, hear the waves booming. The art of Alfred Wallis, and discovering more about his life, unlocked for me the character of ‘The Captain’ in The Waste, who although is not meant to represent the real Wallis, does share many of the same motivations and obsessions. It is important not to romanticise the life of Alfred Wallis – he struggled with poverty and, it would appear, mental health difficulties – but he brought something profound and original into the world, and I hope he gained pleasure from the creation of his art.

The Waste is out now, available in eBook and paperback, and free to read through Kindle Unlimited.

0 Comments

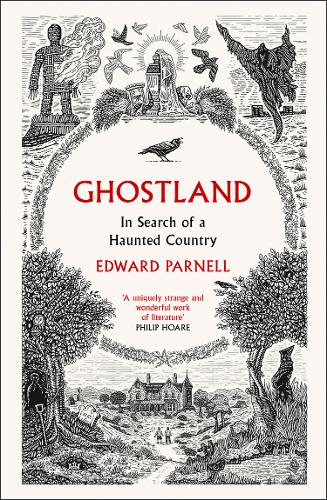

If you spend any time in the lonely places of the British countryside – the deserted beaches, the dense forests, the Fens, the hills and mountains, the still ponds and lakes, the ruins half-swallowed by time – then you’ll be familiar with the occasional fleeting sense of there being something just out of sight, just out of hearing, a sense of watchfulness, of secrets and trauma long-hidden. It is these wild places, and the effect they have on us, that Edward Parnell explores in his outstanding book Ghostland – In search of a Haunted Country. In the best way, Ghostland is a difficult work to categorize. It is a book of haunted landscapes and haunted lives, a book filled with folklore, natural history, psychogeography and cinematic and literary references, all underpinned by the author’s deeply moving personal story. Whether exploring the crumbling cliffs and lonely beaches of Suffolk, or the sprawling Glasgow Necropolis, or the rugged coast and Neolithic moorlands of West Cornwall, and many locations in between, Parnell invokes a powerful sense of place and the stories and ghosts that surround and infuse them. Ghostland shines a light on some of Britain’s finest writers of horror and the uncanny, such as M.R. James, William Hope Hodgson, Arthur Machen and Alan Garner, showing how their obsessions and fears, and connections to their landscape, shaped their creations, often in unsettling ways. Although some of the authors mentioned in the book I am familiar with, there are others whose work I didn’t know, so one of the joys of Ghostland is discovering a list of novels and short stories I now can’t wait to read.

As well as ghostly literary tales, on-screen horrors are explored too, and not just folklore-inflected cinema and television such as The Wicker Man, The Children of the Stones and Jonathan Miller’s peerless M.R. James adaptation Whistle and I’ll Come To You (still an intense, disturbing experience), but also the dark strain of British public information films, which are vividly remembered, most likely in our personal and collective nightmares, by the generation exposed to them. For example, Lonely Water, a nightmarish warning of the perils of swimming in dangerous places (narrated with spine-tingling relish by Donald Pleasance), and Apaches, a terrifying short film I remember being shown at primary school – if the aim of Apaches had been to convince children growing up in rural Britain in the 1970s and 1980s that the countryside was filled with hidden and gruesome threats, then, from my perspective at least, it succeeded… I think anyone reading this book will find some moments of connection and resonance, whether in Parnell’s deep love and reverence for the natural world, his fascination with stories of the uncanny or in his sensitive but unflinching description of his own personal tragedies. For me, Ghostland demonstrates how our cherished places and stories – in any form – can help us manage and make sense of our real-life struggles. The best ghost stories don’t just frighten or excite us, they help to remind us to acknowledge painful memories – our own ghosts of the past – to help us move forward, to help us keep going, even when stricken with loss and grief. From the first page of Ghostland to the last, I fell under its haunted spell; I have no doubt it is a book I will revisit and reread, and I am sure every time I open it, I will find new treasures – and new horrors – buried within its pages.

Stories come alive through the voices of their characters. To capture the natural rhythms and flow of human conversation is not an easy task, but in this blog post, I am going to give some tips on how you can create dynamic dialogue to enhance your storytelling.

There are three key aims your dialogue must achieve:

Keep it real (sort of) Although you want your dialogue to sound natural and to flow, you don’t want to replicate the structure of real speech, which is often full of unfinished sentences, repetition, pauses and stumbles over words – of course, you might want to add these in occasionally when it fits the moment, but do so very sparingly to avoid your dialogue becoming too ragged for the reader to follow.

Keep it brief and avoid small talk

Pages and pages of dialogue can be trying for the reader, so try to keep it focused – avoid any conversation that fails to achieve any of the three key aims mentioned above. Never info dump You should only dispense exposition through dialogue very sparingly – in particular, don’t state things both characters would clearly already know. Dumping exposition risks making your dialogue stodgy and stilted. Give each character a recognisable voice All humans express their thoughts in a unique way. A character’s background should influence the way they speak – their tone, use of language, any slang and dialect phrases. Once you’ve established a character’s voice, make sure you are consistent throughout the story. Show not tell Don’t signpost your characters’ emotions. As people, we’re not always precisely aware of how we feel, let alone be willing or able to express that emotion. Rather than having a character explicitly say ‘I’m angry’ or ‘I’m worried’, try to describe body language as indicators, clues even, for your readers to use. Dialogue tags Of course, when reading dialogue, your reader needs to know which character is speaking. The standard way of doing this is to apply dialogue tags such as ‘She said’ or ‘Jo cried’. Sometimes, additional verbs and adverbs are used such ‘she said sadly’ or ‘Jo cried angrily’ – I find these intrusive, especially if over-used; again, these run the risk of telling not showing the reader how a character is feeling or reacting. I tend the use the bare minimum of dialogue tags, basically just enough ‘he / she said’ so the reader can follow and know who is speaking - I feel this helps the dialogue flow and keeps the reader’s focus on what is being said. My final tip is to read your dialogue scenes out loud – this helps to identify any words or phrases that fail to ring true for the characters.

If you’re interested in my writing, you can get the ebook version of my first novel - The Map of the Known World – for FREE. Please see the following Kindle preview:

Writing a novel is a demanding exercise: it requires imagination, focus, and the stamina and enthusiasm to keep working over a long period. Moments of frustration, drudgery and disappointment are, unfortunately, all part of the process, but there is an even more difficult challenge to overcome – self-doubt. Self-doubt is the voice that whispers: ‘your writing is not good enough – you’re not good enough.’ It can slow your progress, even sinking you towards writer’s block (which I’ve posted about previously). To date, I’ve written four novels (and am drawing close to completion of a fifth) and numerous short stories; I’ve attended writing courses and have read many books on the subject; I’ve also advised and supported other writers on their writing and publication journeys. Despite this, I regularly feel a weighty amount of self-doubt when it comes to writing. The following is a selection of the doubts I often feel… These characters are flat. The story makes no sense. Nobody is ever going to want to read this. I’ve run out of ideas. And there are many, many more… At its worst, self-doubt stifles my creativity, making me hesitate rather than taking positive steps forward.

So, how can you overcome self-doubt? I’m not sure you can completely overcome it, but you can deal with it, and make sure it doesn’t stop you writing. Here are three tips: Manage your expectations: One advantage of self-doubt is that it challenges complacency: as a writer, it is healthy to have the ambition to keep improving your skills. However, there is a difference between ambition and expectation; the former is a positive, vital approach, the latter is a burden. An expectation can say ‘my writing must always be great’ - this sounds fair enough at face value, but dig a little deeper: is it reasonable to expect your writing to always be great? Of course it isn’t, but if you somehow believe this, then what is the inevitable outcome if your writing falls below par? You’ll feel like you are wasting your time, and that your work is worthless. This will only add further fuel to your inner self-critic, and this critic will do everything to convince you to stop writing. Cut yourself free from expectations – instead, just focus on trying to get better, trying to improve. Keep reading: Yes, it is tempting to compare yourself to other authors and when you read their books, their work will seem so polished, so impressive. But remember: their books have been fully developed, edited, proof-read – don’t compare them to your work in progress. So, keep reading as many books as possible – keep reading for inspiration and to learn more about different writing styles. Just keep going: When you’re hit by self-doubt, when your inner critic is at its most vocal, it is easy – and understandable – just to stop writing. But the best way to fight your self-doubt is to keep writing. Even if you’re writing badly, it is much better than not writing at all – if you stop writing, then your inner critic has won, and that can’t be right! Just write something, anything and see what happens. Don’t overthink your writing and never look for perfection. Just write for the joy of writing and you’ll create something, however small, that is worthwhile and this increase both your confidence and enjoyment. And if you keep going, I promise you the self-doubt will pass - it will come back, of course, but take advantage of the times when you’re feeling more confident, and use these to help keep going through the tougher moments. How do you try to overcome self-doubt as a writer? Add a comment and join the conversation. In this latest post chronicling the writing of This Sacred Isle, I'll be looking at how I used description within the novel. I have to declare an interest – I love writing descriptive passages. Tiny, quirky details fascinate me, and for a novel such as This Sacred Isle, it was important to create a sense of a vivid, living, breathing world. I always try to use all the senses rather than simply giving a visual description of a scene; this gives a richer impression for the reader. As mentioned in the research post, where possible I like to visit locations pertinent to the story - just listening to the sounds of a location, or taking in the smells (pleasant or otherwise!) gives me a deeper connection, a deeper feeling of place. In This Sacred Isle, I wanted the landscape to almost be a character, for its moods and history to have an effect upon those who live there. For example, the following is a short passage from the book:

"They crunched over frozen dead leaves and bracken, disturbing birds feeding on the woodland floor. A red squirrel scampered up the nearest tree, startled by the unexpected intruders to its realm. Although dimmed by the cold of winter, the wood still assaulted Morcar’s senses with unfamiliar sounds, smells and sights: the rhythmic creaking of ice-stiffened branches; a jay’s screaming call; the moist, cloying smell of decomposing leaf litter. An eerie, echoing wolf-howl carried on the wind. The wood unnerved Morcar, he felt out of place, adrift in a world familiar on the surface, but with strange undercurrents." I made use of a colour palette within the story, to suggest move and subtle changes in the plot. For example, the story of This Sacred Isle begins in winter. This is very deliberate, as I wanted to suggest a world frozen in stasis – Morcar’s people are bound by their culture and a very specific worldview (as are many other characters we encounter in the book). In this part of the story I used (obviously!) a wintry palette of white, greys and browns. As the novel progresses, and Morcar’s experience broadens, we move through the seasons, which is not just a temporal sequence but is also designed to reflect movement within Morcar’s character and the effect his actions have on those around him. However, my love of descriptive writing carries an inherent risk! I have to be wary of my tendency to over-describe and drift into passages of longueur – as important as description is to the process of creating a novel, it should never slow the narrative. When editing my novel I cut most brutally any passages of description; they need to work very hard to convince me of their necessity. This sometimes means losing some sentences I favoured, but unless they served a narrative or character function, then it becomes hard to justify keeping them. It is a question of balance – the world I want to create within This Sacred Isle needs to be layered, with a ‘dirt beneath the fingernails’ realism combined with a sense of mysticism. This requires moments of detailed description but at the same time I need to drive forward the narrative and shape a compelling, page-turning tale for the reader. Did I get the balance right? Mostly I think so, hope so, but I guess it is only the reader who can judge. How do you approach descriptive writing? What kind of descriptive writing do you love to read? Post a comment and join the conversation... |

Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed