|

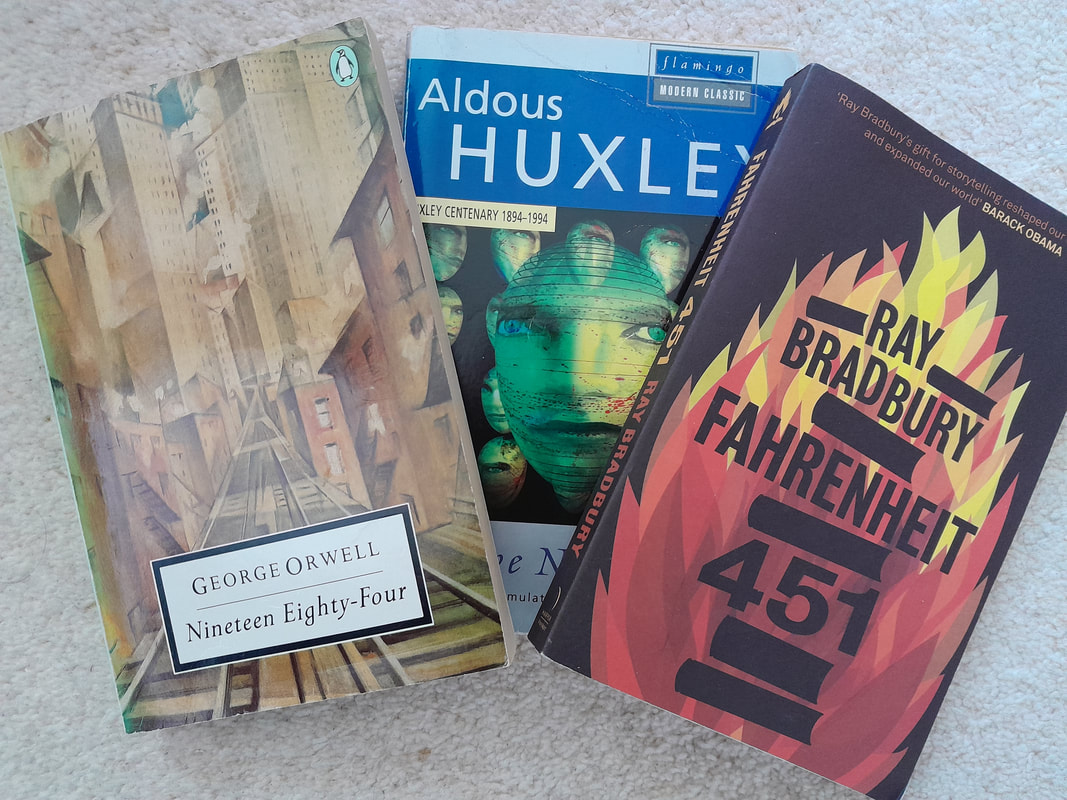

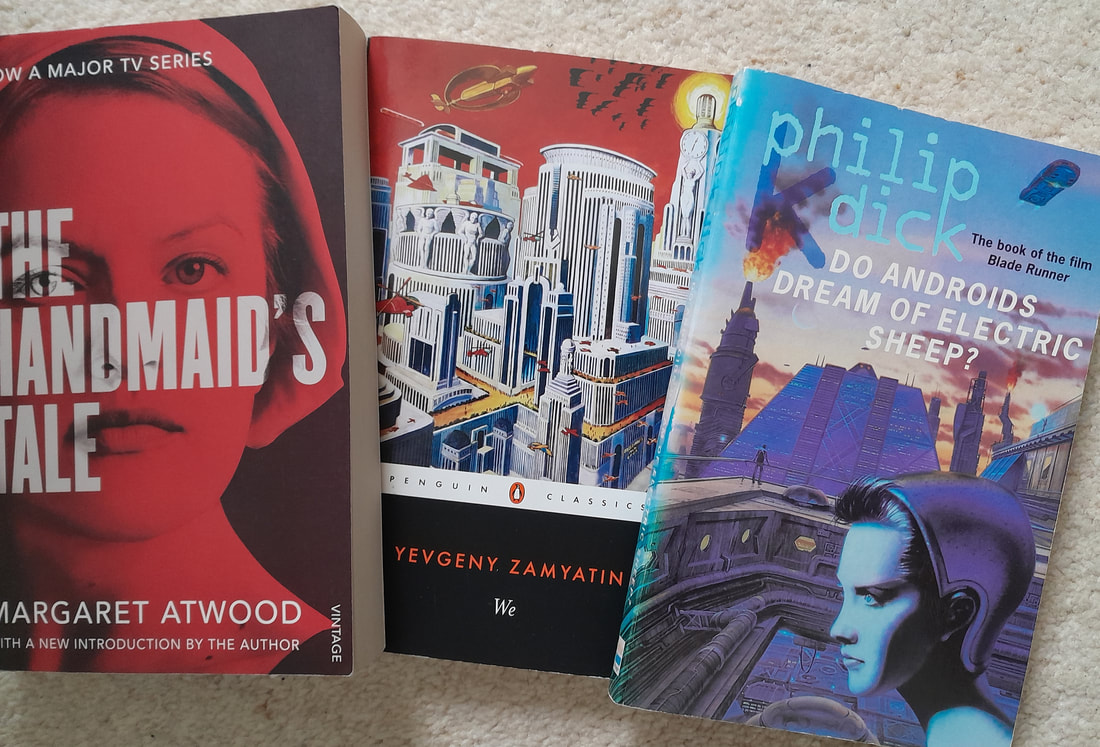

Dystopian science fiction is a genre I've long enjoyed and when I came to write The Waste, there were several novels that influenced and inspired me. Brave New World by Aldous Huxley Brave New World is often cited as one of the most influential and prophetical books of the twentieth century. Set in the far future, the World Controllers of the story have strived to create a perfect world. Every individual receives pre-natal / post-natal conditioning so as to accept his or her position in society, from the Alpha-Plus ruling class to the Epsilon-Minus Semi-Morons who are bred to perform menial tasks. This society is perfectly ordered, and this control is strengthened through the state-endorsed use of the drug soma, and other pleasurable distractions. In many senses, the people of the novel are controlled by their pleasure and distractions; when life is so good and so easy, why even think to challenge the status quo, what would be the purpose? This is not a tyranny of brutal physical oppression, enforced by military strength and prison camps, but a tyranny in which the citizens are imprisoned in a gilded-cage of amusement and ease. I found this a fascinating concept: that a dystopian could be so insidious, almost hiding in plain sight with a benevolent façade. Some of the thematic elements of Brave New World certainly influenced parts of The Waste. In the society shaped by the alien Seraphim, people are encouraged to focus only on their own needs and pleasures, with any concerns for wider society deemed odd, even suspicious – like the genetically bred humans of Brave New World, do they even notice they are living in a dystopian world, or if they did, would they care? The titular Waste of my novel, a vast open-air prison, was also in part influenced by the Savage Reservation visited by Bernard Marx and Lenina Crowne in Brave New World. Brave New World still impresses with its brilliant invention and wit, and as time passes, I’d argue Huxley’s novel simply becomes more and more relevant, and perhaps more and more troubling. Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell To the best of my memory, Nineteen Eighty-Four was the first dystopian novel I read and it is a book that certainly leaves a deep impression and although I have re-read it several times, its impact is never lessened. Airstrip-One feels like a nightmare, a crucible of relentless pressure: the constant surveillance, the crushing conformity, the lingering danger of arrest and the sheer misery of the horrible food, the bitter cold and the dilapidated living conditions. And in this wretched world, mutilated by an endless three-sided war, anger and sexual frustration are channeled into hatred towards enemies of the state real and imaginary. The most memorable display of this is the Two Minute Hate, where the Party Members are whipped into a frenzy of loathing. Outside of the Party members, the rest of the population of Airstrip-One, known as the proles, are distracted from political involvement by mass entertainment, a dubious National Lottery and sport (and, where necessary, the iron fist of state security). And it is difficult to read Winston Smith’s diary entry about his visit to the cinema, as he describes a film in which ships full of refugees are bombed in the Mediterranean, and not consider our own society’s indifference, even hostility, as children and adult alike drown in the very same sea Orwell described. In The Waste, this influenced the character of Oswald Beckett who shows no sympathy to the desperate refugees for whom he is responsible, seeing them not as people but as data to be controlled as part of reaching budgetary targets and developing his blossoming career. Nineteen Eighty-Four is undoubtedly a book with profound comments on politics and society, it remains a story with a very human focus. We see Winston Smith’s suffering in everyday terms: the constant bombardment of propaganda, his blunt razors, the crumbling cigarettes, his coughing fits and varicose ulcers. The readers sees the misery and loneliness of an individual crushed and dehumanized by the tools of political terror. This approach influenced me when I wrote The Waste, and rather than take a broad view, I wanted to explore the society created by the alien Seraphim mainly through the lens of one ordinary person. Nineteen Eighty-Four has had a huge influence on me as a reader and a writer. Orwell’s novel continues to burn with fury is a warning to us all, a warning I believe will endure through the ages. Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury In the future society of Fahrenheit 451 all books are illegal and if any are discovered, they are burned, for books are considered disruptive, dangerous, a cause of unhappiness. Guy Montag is a ‘fireman’, whose job is to find books and destroy them. Within this world, books are no longer valued and instead people have moved to new and addictive forms of media, encapsulated by the ‘parlour walls’, screens that fill entire walls and interact with the viewers. This media is seen as a better fit for an increasingly rapid pace of life and shortened attention spans. Initially settled in his job and home life, Montag’s unease with this society grows as he feels increasingly uncomfortable with the mind-numbing ‘entertainment’, which addicts so many people, and he begins to doubt the wisdom of book burning, especially when he sees the lengths some custodians are willing to go to protect their books. Soon, Montag begins hiding books himself and the experience of reading starts to change him… These ideas certainly influenced parts of The Waste. For example, although in my novel, books are not banned as such, they are considered quaint, redundant even – they have simply been supplanted by easier, less demanding media. The alien Seraphim encourage humans to only consider the present, to ignore or forget the pain of the past; books, as stores of knowledge, ideas and experiences, play no part in this world view. Museums and art galleries likewise are considered irrelevant and so close down out of apathy rather than a direct decree – of course, the Seraphim are not above appropriating works of human art when so inclined and hoard their treasures out of public view. Other books: Although these three books influenced my writing of The Waste, there are several other dystopian novels that were significant touchstones too, such as The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood, We by Yevgeny Zamyatin and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick, and I would definitely recommend these all as powerful, thought-provoking reads.

The Waste is out now, available in eBook and paperback, and free to read through Kindle Unlimited.

5 Comments

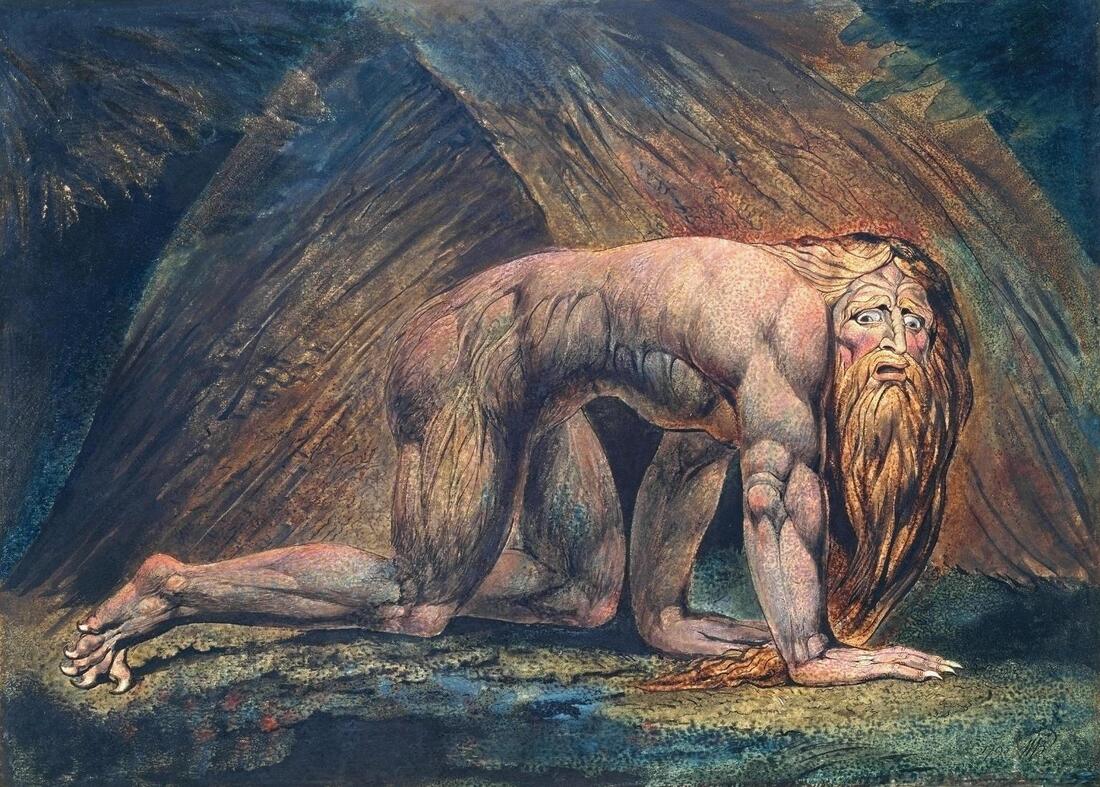

Like any author, I draw upon a broad range of inspirations when writing a book, and for me, visual art has always informed and influenced my writing. Although far from blessed in my drawing and painting skills, I’m rarely happier than when wandering around an art gallery! In this blog post, I am going to focus on four artists who have been particularly important and inspiring to me when I was working on my new novel The Waste. William Blake I have long been fascinated by the work of visionary painter and poet William Blake (1757-1827). His art is both highly personal and highly original, infused with his rebellious spirit and enormous imagination. Encompassing biblical and mythological themes, the delicate strangeness of Blake’s work is powerful and seeing the collection of his work is always a highlight of any visit to the Tate Britain. Through his art and prophetic books, Blake developed a very personal mythology with a host of symbolic characters, and this mythology, along with the graceful, idealised human figures in Blake’s art, was a significant influence for me when writing The Waste, especially when developing the characteristics of the alien Seraphim. The act of developing and writing a novel can be a hard slog, but to spend time researching and thinking about Blake’s art and writings was a pleasure in itself. Paul Nash If I have such a thing as a favourite artist, then I think it would be Paul Nash (1889-1946). Whether it’s the raw, uncompromising power of his First World War art, the melancholy of his Dymchurch paintings or the mythical energy of his work inspired by the Avebury stone circle, I find his work captivating, his symbols resonant and meaningful. Perhaps Nash’s best-known work is We Are Making A New World. I saw the original for the first time in an exhibition at the Imperial War Museum in London. Few paintings have had such an impact on me – the battle-ravaged, brutalised landscape reflected not only the hideous violence of war but Nash’s own emotional experience of the conflict. Consider the pallid sun peeking through the blood-red tide of clouds – is it striving to bring light and hope to the shattered world below, or is it too frightened to peer at the horror Mankind has inflicted? This painting makes an appearance in The Waste and Spare’s experience of viewing it certainly echoes my own. Through his paintings Paul Nash demonstrated an intense relationship with landscape, not just recording what his eyes saw, but adding deeply personal levels of symbolic meaning, giving the landscapes he portrayed an animated, vital presence. From his early drawings and paintings, influenced by Samuel Palmer and William Blake, to the harsh angles and blade-like waves of his Dymchurch work, which evoke such a sense of emptiness, of loss and depression, the landscapes of Nash are alive and mythic. This sense of place, the genius loci, as Nash referred to it when he described places such as Avebury, was something I wanted to reflect within my novel. The titular Waste of the book is both a literal and symbolic landscape, where the layers of human history are almost a tangible presence. I have no doubt Paul Nash will remain a primary inspiration for my writing. Dame Elisabeth Frink My first, very striking, encounter with the work of Dame Elisabeth Frink (1930-1993) took place in Bury St Edmunds in my home county of Suffolk. In the grounds of St Edmundsbury Cathedral stands a bronze statue of Edmund, a ninth century king of East Anglia. After being defeated in battle by the Great Viking army, it is said Edmund refused his enemies’ demand to renounce Christ and so was beaten, shot through with arrows and beheaded. Legend tells the Vikings threw Edmund’s severed head into the forest, but it was soon retrieved by those loyal to the king when they followed the cries of a mysterious wolf. Frink’s statue shows King Edmund as a young man, a cross grasped in his hand. This is not a caricature of a warrior or a king – there is pride in Edmund’s face but a sense of vulnerability, his slender body is fragile. Frink’s Edmund is very much a king, a saint, and a martyr, but still a human being. This often-unsettling combination of history, myth and human frailty seems to be present throughout much of Frink’s art. During the writing of The Waste, I was especially interested by Frink’s goggle head sculptures; shaped by Frink’s interest in themes of masculine aggression, the goggle heads’ sense of faceless authority very much shaped the look and attitude of the Shades, the cold, impersonal, unaccountable police force of my novel. The goggle head sculptures avoid eye contact, concealed behind polished headgear – they are dehumanised and as such offer a threat that cannot be reasoned with. The Shades in The Waste are human, but just as their visors hide their human faces, their humanity is also hidden and they appear almost machine-like, robotic. The unsettling and enigmatic nature of Elisabeth Frink's art continues to be both fascinating and inspiring. Alfred Wallis Alfred Wallis (1855 - 1942) produced profoundly personal art, painting images of ships, boats, Cornish villages and the sea. With no formal art training, Wallis only took up painting after his wife’s death – with little money for materials, he mostly painted on found pieces of cardboard. Wallis painted from memory, drawing on his sea-faring experiences, to capture a rapidly disappearing way of life. Wallis’s limited palette and distorted perspective give his work a distinctive look. Within his paintings, Wallis played with size and scale of objects, and although the paint is roughly applied, he often achieved high levels of detail. Wallis’s instinctive compositions give his paintings real vitality – you can almost taste the briny air, hear the waves booming. The art of Alfred Wallis, and discovering more about his life, unlocked for me the character of ‘The Captain’ in The Waste, who although is not meant to represent the real Wallis, does share many of the same motivations and obsessions. It is important not to romanticise the life of Alfred Wallis – he struggled with poverty and, it would appear, mental health difficulties – but he brought something profound and original into the world, and I hope he gained pleasure from the creation of his art.

The Waste is out now, available in eBook and paperback, and free to read through Kindle Unlimited. Landscape, and a sense of place, has always been important in my writing and my new science fiction dystopian novel The Waste is no exception. The novel moves through London, Gippeswic (an alternate version of Ipswich in Suffolk) to the Waste, which is a massive open-air prison covering a large swathe of south-western England. In this blog post, I will cover some of the real-world locations that helped inspire my novel. London Parts of the novel take place in (a much changed) City of London, with buildings such as the Shard, Saint Paul’s Cathedral, Saint Mary Woolnoth church and Liverpool Street Station appearing in thinly veiled forms. This is an area of London steeped in history, which I always find fascinating and enjoy walking around (especially when quieter at the weekends) and it formed an interesting backdrop to parts of the story. Within the novel, these flashes of history also contrast with the society the Seraphim are encouraging humans to build: a society focused only on the present, only on personal gain and pleasure. The inclusion of Saint Mary Woolnoth church is also a nod to The Wasteland by TS Eliot, which inspired some of the imagery in the novel. Avebury World Heritage site The area around Avebury in Wiltshire contains an extraordinary cluster of monuments dating to the Neolithic and Bronze Age, including the famous Avebury Stone circle, Silbury Hill and West Kennet Long Barrow. Having been fortunate enough to visit this area on a few occasions, it is difficult to put into words the atmosphere this landscape exudes. As you walk around the henge and stone circle at Avebury, or face the imposing mass of Silbury Hill, or walk up to the mysterious West Kennet Long Barrow, there is a sense of deep time, of landscape shaped by countless layers of human history. From the earliest stages of writing The Waste, Avebury and the surrounding area always formed a key location in the story. In the book, the henge and stone circle at Avebury appears as Havock, the chief settlement of the dreaded Mohock clan, while Silbury Hill emerges in grisly fashion as their chosen place for executions. West Kennet Long Barrow also has a fleeting but important appearance. One of the reasons Avebury interested me in the first place was the work of artist Paul Nash, who has long been one of my favourite artists. Nash had a profound sense of landscape, with a powerful emotional attachment to certain places such as Avebury and Dymchurch, places which possessed a quality he referred to as the genius loci. Although the Waste is a prison, and a dangerous and savage place, it is also less touched and polluted by the modern world – as well as being at times horrifying, I wanted the Waste to be a dreamlike landscape, rich with a sense of history and symbolism. I believe this quote from Paul Nash encapsulates the sense of what I was reaching for:

"The divisions we may hold between night and day - waking world and that of dream, reality and the other thing, do not hold. They are penetrable, they are porous, translucent, transparent; in a word they are not there." 'Dreams', undated typescript, Tate Archive The settings in The Waste are key elements in the novel, both challenging and revealing the characters, and although this is science fiction, they help achieve a sense of reality and history. The Waste is out now, available in eBook and paperback, and free to read through Kindle Unlimited. Image of St Paul's Cathedral by Raygee78 from Pixabay Magic. The very word itself conjures so many different ideas, images and symbols. The story of magical beliefs is as old as the history of humanity itself, and it is this vast tapestry Chris Gosden explores in his excellent book, The History of Magic – From Alchemy to Witchcraft, from the Ice Age to the Present. The scope of the book is remarkable; we journey from the Ice Age, through the earliest civilisations in Egypt, Mesopotamia and China, across the Eurasian Steppe to explore shamanism, the magics of the Americas, Africa and Australia, and the development of magic in Europe, all to the modern day. It could be easy to get lost in such an enormous canvas and there is much for the reader to absorb, but I never found the book less than highly readable. The inclusion of tables outlining the chronology of the periods being discussed adds valuable and helpful context, especially when the historical timescales are often lengthy. Through an anthropological and archaeological study of magic, Gosden argues passionately (and persuasively) for a change of mindset, rejecting the long-embedded views of magic (especially in Western perspectives) as primitive and backward. Drawing on practices and beliefs from throughout human history, Gosden asserts magic encourages a holistic, connected view of humanity, linking us to our planet through moral and practical relationships. As is outlined in the book, human understanding of the mechanics of the world and the universe is often considered to be divided into three key areas of thought, starting with magic, before moving through religion to reach science, an evolution in thought. Gosden argues instead the three strands of thought form a ‘triple-helix’ and have always been interconnected and inter-reliant.

Every chapter of The History of Magic brings fresh discoveries and intriguing characters from the past (from kings, shamans, witches and many more), and underlines how magic has and remains part of the human experience I found The History of Magic a thought-provoking and spellbinding read. Written with the greatest of respect for magical practices and beliefs, it is a book of deep scholarship and of relevance to our times, and one I am sure I will return to for pleasure and inspiration. If you’re interested in the history of magic, I would also strongly recommend The Book of English Magic by Philip Carr-Gomm & Richard Heygate, a gripping and fascinating work. In the summer of 1962, with his mother recuperating from an illness, young Luke Kirby is sent to stay with his Uncle Elias, (who Luke has never met) in a village called Lunstead. Elias soon reveals himself to be a magician, and he is keen to pass his skills onto his nephew. But as Luke begins his magical apprenticeship, a deadly horror reveals itself… Written by Alan McKenzie, and illustrated by John Ridgway and Steve Parkhouse, Summer Magic: The Complete Journal of Luke Kirby is a collection of tales (originally printed in 2000AD), which coalesce into an overall story arc. The stories are varied, for example: The Night Walker, where Luke must confront a vampire; Sympathy for the Devil, where Luke travels to hell (an unnervingly original version of the underworld) in search of his father; and (possibly my favourite in the book) The Old Straight Track, which delves deep into British mythology and folklore, becoming a memorable folk horror tale infused with paganism, during which Luke—guided by the mysterious alchemist called Zeke— travels through a landscape marked by ley lines, stone circles and long barrows. For me, there are echoes of the work of Alan Garner with the close connection between the landscape and the characters. Summer Magic is a compelling collection, with stories that in places pack a disturbing punch. Throughout the book, the beauty and mystery of the English countryside is beautifully evoked through the writing and the stunning artwork. And beneath that beauty, and within the sleepy streets of the villages and little towns, true horrors lurk… Through all the stories run themes of death, family and horror, and as Luke develops his magical and alchemical skills, he learns that all actions, however well-intentioned, have consequences. Within Summer Magic, there is more than a little sense of the challenging, hard-edged fare of 1970s British cinema and TV (this is definitely a story for the Scarred for Life generation). Summer Magic: The Complete Journal of Luke Kirby is a great collection—a coming-of-age tale but with a 2000AD edge, an excellent example of the dazzling range of creativity that has poured from the comic’s pages over the decades. If you’re read and reread all of the Harry Potter books, or just finished binge-watching series 4 of Stranger Things, you will find much to enjoy in this dose of Summer Magic. If you want to find out more about Summer Magic: The Complete Journal of Luke Kirby, I'd recommend this excellent short introductory video made by 2000AD: Britain has brought back the death penalty, and Adam Cadman, convicted of murder, finds himself the first person to be hanged since 1964. But as the noose tightens around his neck, Cadman is transported to the Mazeworld, a world in another dimension, and there this reluctant hero begins his adventure. For in this world of strange creatures and mighty warriors, Cadman is believed to be the Hooded One, a hero of old who can lead the oppressed masses in rebellion against the Mazeworld’s cruel masters… It’s been a long time since I last dipped into the wild and weird world of 2000AD; although not a regular reader of the comic as a young person, characters such as Nemesis the Warlock left an indelible memory. I decided to start my journey through 2000AD classics with Mazeworld, and I was not disappointed. Written by Alan Grant and illustrated by Arthur Ranson, Mazeworld is truly a work of epic fantasy, bold and imaginative. There is action aplenty, all expertly paced and beautifully illustrated – the artwork of Arthur Ranson is always stunning and at times simply breathtaking. Some of the panels could be frames from epic movies, full of energy and excitement. It is a powerful story too, thematically dense, and rich in mythological and folkloric imagery such as the Green Man. The world building is staggering - the architecture of this other dimension, inspired by the Aztec and ancient Egyptian cultures, looms over the panels, almost making the Mazeworld a character in its own right, with visual treats such as the enormous ziggurats, the many carved monuments to old gods who look on in silent judgement, and the twisted alleyways and dungeons. The gritty rundown realism of the Mazeworld plays effectively alongside the broader fantasy elements such as maze monsters and flying lizards – this serves to make the world of the story all the more convincing and immersive. Cadman is certainly far from the traditional hero – upon his first ‘arrival’ in the Mazeworld he is a coward, concerned only with his own welfare and interests; but gradually, through many trials and failures, he begins to develop into the hero the suffering folk of the Mazeworld so desperately crave. Mazeworld offers an unsettling vision of evil - the enemies Cadman face in this other dimension are truly horrific, from the scheming Lord Raven, to the spine-chilling Dark Man with his deadly third eye, and the final demonic foe… Atmospheric and immersive, Mazeworld is a treat for any lover of fantasy fiction and tales of the uncanny. I was so engrossed in the unfolding plot, I am sure there are many subtleties I missed, so I look forward to discovering them when I re-read the book and once more become lost in the Mazeworld. If you want find out more about Mazeworld, I'd recommend an excellent short introductory video made by 2000AD:

All authors draw on a wide range of inspirations when creating their stories, such as real-life experiences, places they have visited, concerns about the world and society, books they have read. For me, visual art has always inspired and influenced my writing. I cannot claim to be an expert in art history, and as much as I enjoy sketching my artistic skills are limited at best, but I find it an endlessly absorbing subject and a way of finding different perspectives on the world. By offering us a safe space to consider and explore feelings and fears we otherwise feel uncomfortable in confronting, art can help us all feel a little less alone in this world.

In this blog series, I am going to focus on four artists who have been particularly important to me and my creative work: Ian Miller, Elisabeth Frink, Paul Nash and Alfred Wallis. In this post, I am going to discuss the work of Paul Nash. Sometimes your appreciation of an artist develops over time – you slowly connect to their style, craft and symbolism. Other artists are like love at first sight: the first glimpse of a painting or sculpture creates an instant connection, an instant meaning. For me, Paul Nash is definitely in the latter category. Whether it’s the raw power of his First World War art, the melancholy of his Dymchurch paintings or the mythical energy of his abstract work inspired by the Avebury Stone Circle, I find his work endlessly fascinating, his symbols resonant and meaningful. I even named my small publishing company after Nash’s series of Monster Field photographs.

One of the most influential British artists of the twentieth century, Paul Nash demonstrated an intense relationship with landscape, never just recording the topography, not just recording what his eyes saw; instead he added deeply personal levels of symbolic meaning, giving the landscapes he portrayed an animated, vital presence.

Born in 1889, Nash’s early work was influenced by the Pre-Raphaelites and William Blake, and produced drawings and paintings of dream-like landscapes, often peopled with mysterious figures. In particular, Nash filled his trees with life, almost giving them personalities of their own: "O Dreaming trees,

As with millions across the world, Nash’s life changed with the outbreak of the First World War. He enlisted in the Artists’ Rifles in September 1914 and was stationed in England until deployed to the Ypres Salient in March 1917. This spell on the Western Front proved short-lived, as Nash suffered a non-combat injury and was invalided home. He returned to Belgium in October 1917 as an official war artist, depicting the shattered landscape.

Not only did war change Nash’s life, it also transformed his art. Perhaps the most famous painting of Nash in this period is We Are Making A New World. This is a painting I had seen reproduced many times but I saw the original for the first time in an exhibition at the Imperial War Museum in London. Few paintings have had such an impact on me – the ravaged, brutalised landscape reflected not only the violence of war but Nash’s own emotional experience of the conflict. Sometimes I see this as a hopeful painting; other times I feel it is filled with despair. Look at the pallid sun peeking through the blood-red tide of clouds – is it striving to bring light and hope to the shattered world below, or is it too frightened to peer at the horror Mankind has inflicted?

After the war, Nash moved to Dymchurch in Kent, where he made a series of stark paintings of the sea and coastal defences. Nash, who had nearly drowned as a child, portrays the sea as menacing and cold – the harsh angles and blade-like waves are as threatening and desolate as No-Man’s Land, the grim memories of war spilling over Nash’s work even in peacetime. To me, the paintings evoke a sense of emptiness, of loss and depression.

The Dymchurch paintings show again Nash’s connection to landscape, and it is this connection that has most influenced me as a writer. For example, when writing my novel This Sacred Isle, Nash’s symbolic landscapes remained at the forefront of my thinking. I wanted to present the landscape of that story as liminal and to show traces of the history it had witnessed, where there exist forces and influences beyond what is normally visible. To quote Nash:

"The landscapes I have in mind are not part of the unseen world in a psychic sense, nor are they part of the Unconscious. They belong to the world that lies, visibly, about us. They are unseen merely because they are not perceived."

Paul Nash had a powerful emotional attachment to places such as Avebury, which he said possessed a quality he called the genius loci.

This sense of places having its own 'character' or 'spirit' was something I tried to create within This Sacred Isle, for example, in the scene Morcar meets the Stag Lord, a scene that plays out in a dreamlike, symbol-laden landscape. A quote from Paul Nash captures the feeling I was trying to achieve: "The divisions we may hold between night and day - waking world and that of dream, reality and the other thing, do not hold. They are penetrable, they are porous, translucent, transparent; in a word they are not there."

Nash’s connection with Avebury inspired me to visit the stone circle, and once there I could understand why it held such a fascination for the artist – combined with the surrounding landscape, encompassing sites such as Silbury Hill and West Kennet, it forms such an evocative place, steeped in history and myth. Avebury is an important location in my next novel, Second Sun, and this is in no small part due to the influence of Paul Nash – for me, and I’m sure many other people, his work will remain an ongoing inspiration.

Part 1 - Ian Miller

Part 2 - Alfred Wallis Part 3 - Elisabeth Frink If you’re interested in my writing, you can get the ebook version of my first novel - The Map of the Known World – for FREE. Please see the following Kindle preview:

All authors draw on a wide range of inspirations when creating their stories, such as real-life experiences, places they have visited, concerns about the world and society, books they have read. For me, visual art has always inspired and influenced my writing. I cannot claim to be an expert in art history, and as much as I enjoy sketching my artistic skills are limited at best, but I find it an endlessly absorbing subject and a way of finding different perspectives on the world. By offering us a safe space to consider and explore feelings and fears we otherwise feel uncomfortable in confronting, art can help us all feel a little less alone in this world.

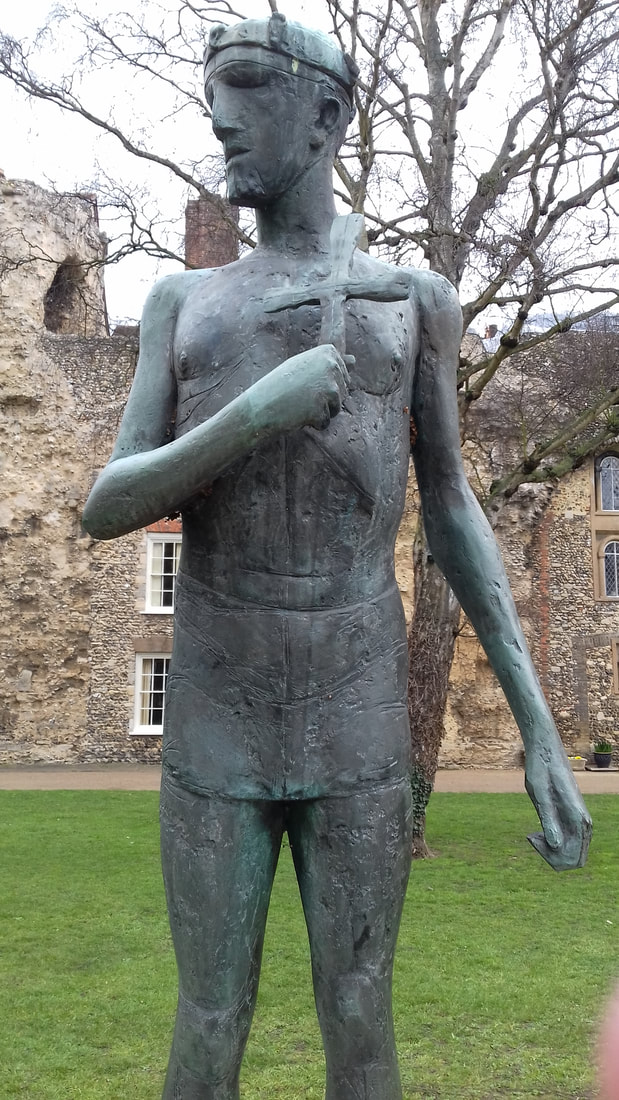

In this blog series, I am going to focus on four artists who have been particularly important to me and my creative work: Ian Miller, Elisabeth Frink, Paul Nash and Alfred Wallis. In this post, I am going to discuss the work of sculptor Elisabeth Frink. I first encountered the work of Dame Elisabeth Frink (1930-1993) in Bury St Edmunds in my home county of Suffolk. In the grounds of St Edmundsbury Cathedral stands a bronze statue of Edmund, a ninth century king of East Anglia.

After being defeated in battle by the Great Viking army, tradition says Edmund refused his enemies’ demand to renounce Christ and so was beaten, shot through with arrows and beheaded. Legend tells the Vikings threw Edmund’s severed head into the forest, but it was retrieved by those loyal to the king when they followed the cries of a mysterious wolf.

Frink’s statue shows King Edmund as a young man, a cross clasped in his hand. This is not a caricature of a warrior or a king – there is pride in Edmund’s face but a sense of vulnerability, his slender body is fragile. Frink’s Edmund is a king, a saint, a martyr, but still a human being. This combination of history, myth and human frailty seems to be present throughout much of Frink’s art. Born in Suffolk, Elisabeth Frink studied at the Guildford School of Art and was part of a post-war group of British sculptors, known as the Geometry of Fear School. Frink’s sculptures often depict men, birds, dogs and horses. My favourite work by Frink is Bird (1952). A few years ago I was lucky enough to visit the Tate St Ives, and of all the wonderful paintings and sculptures in the gallery, Bird stopped me in my tracks – with its alert, menacing stance and fierce beak, it seem to be an archetype of the hard tooth and claw of nature. Bird seems to channel a sense of ancient elemental forces, almost like a deity, a ferocious god demanding propitiation.

When writing my current novel, Second Sun, I was very taken by Frink’s goggle head sculptures; shaped by Frink’s interest in themes of masculine aggression, their sense of faceless authority very much shaped the look of the Shades, the cold, impersonal police force of my story. The goggle head sculptures avoid eye contact, concealed behind polished headgear – they are dehumanised and offer a threat that cannot be reasoned with.

I’m still learning more about Elisabeth Frink’s art, and I’m sure her work will remain enigmatic, unsettling and continually inspiring.

Part 1 - Ian Miller Part 2 - Alfred Wallis Part 4 - Paul Nash

If you’re interested in my writing, you can get the ebook version of my first novel - The Map of the Known World – for FREE. Please see the following Kindle preview:

All authors draw on a wide range of inspirations when creating their stories, such as real-life experiences, places they have visited, concerns about the world and society, books they have read. For me, visual art has always inspired and influenced my writing. I cannot claim to be an expert in art history, and as much as I enjoy sketching my artistic skills are limited at best, but I find it an endlessly absorbing subject and a way of finding different perspectives on the world. By offering us a safe space to consider and explore feelings and fears we otherwise feel uncomfortable in confronting, art can help us all feel a little less alone in this world.

In this blog series, I am going to focus on four artists who have been particularly important to me and my creative work: Ian Miller, Elisabeth Frink, Paul Nash and Alfred Wallis. In this post, I am going to discuss the work of painter Alfred Wallis. One of the most inspiring and original British artists of the 20th century, Alfred Wallis (1855 - 1942) produced deeply personal art, painting images of ships, boats, Cornish villages and a constantly changing sea. With no formal art training, Wallis took up painting after his wife’s death – with little spare money, he mostly painted on found pieces of cardboard. A former fisherman and marine supplies merchant in Cornwall, Wallis painted from memory, drawing on his sea-faring experiences, capturing a disappearing way of life: “What I do mostly is

His limited palette and distorted perspective give his work a distinctive look. Wallis played with size and scale of objects in his paintings, and although the paint is roughly applied, he often achieved high levels of detail. His untrained, naïve style influenced artists such as Ben Nicholson and Christopher Wood, and while he made little money from his works and died in the Madron poorhouse, his paintings helped pave the way to St Ives becoming an important centre in the development of modern art.

Art is absolutely central to Second Sun, the SF book I am currently writing, especially the concept of ‘Outsider’ or ‘Naive’ Art. I find drama in Wallis’s work; his instinctive compositions give his paintings true vitality. His paintings are direct and active – you can almost taste the briny air, hear the waves booming. Wallis had an emotional, almost mystical connection with the sea, ships and the Cornish coast.

I love the sense of an artist expressing a deeply personal, unorthodox view of the world. The work of Alfred Wallis, and discovering more about his life, unlocked for me the character of ‘The Captain’ in Second Sun, who although is definitely not meant to represent Wallis himself, does share many of the same motivations and obsessions. It is important not to romanticise Alfred Wallis – despite the high regard with which he is now held as an artist he struggled with poverty and, it would appear, mental health difficulties – but he brought something profound and original into the world. I like to think that when he was painting, Wallis was soothed in body and mind as he drew on his memories to sail once more on those broiling seas, and capture the essence of a world otherwise lost. And I like to think of how the paintings created by a quiet, solitary man from a little Cornish fishing town reached out and influenced countless others across the art world and beyond.

If you’re interested in my writing, you can get the ebook version of my first novel - The Map of the Known World – for FREE. Please see the following Kindle preview:

All authors draw upon a wide range of inspirations when creating their stories, such as real-life experiences, places they have visited, concerns about the world and society, books they have read. For me, visual art has always inspired and influenced my writing. I cannot claim to be an expert in art history, and as much as I enjoy sketching, my artistic skills are limited at best, but I find it an endlessly absorbing subject and a way of finding different perspectives on the world. By offering us a safe space to consider and explore feelings and fears we otherwise feel uncomfortable in confronting, art can help us all feel a little less alone in this world.

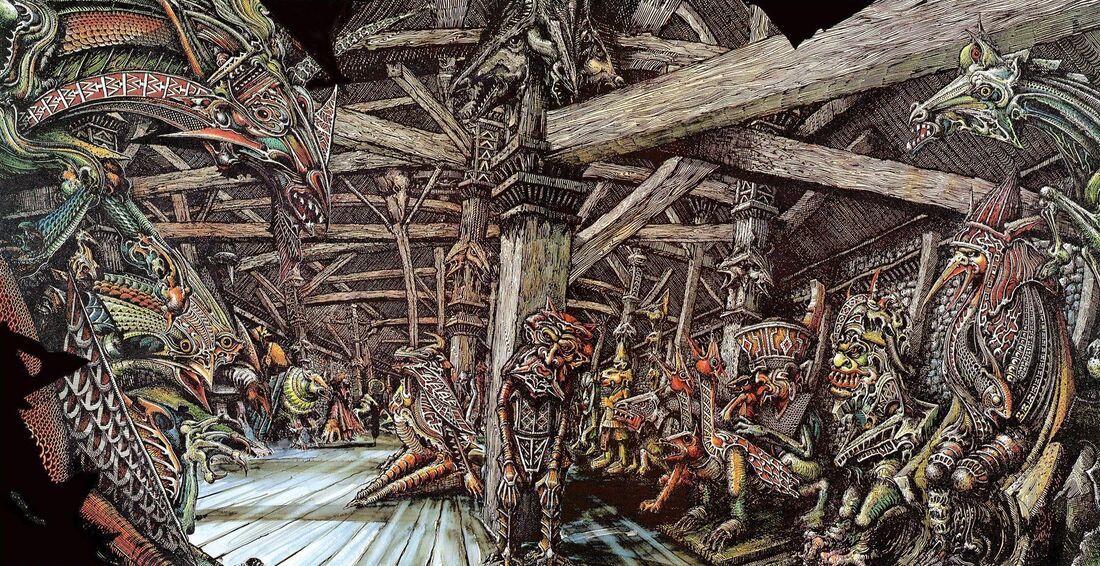

In this blog series, I am going to focus on four artists who have been particularly important to me and my creative work: Ian Miller, Elisabeth Frink, Paul Nash and Alfred Wallis. In this post, I am going to discuss the work of British fantasy artist Ian Miller. Since childhood I have loved the books of J.R.R. Tolkien, and my first encounter with the artwork of Ian Miller was in the book A Tolkien Bestiary; many beautiful and atmospheric images filled the pages of this book, but for me Miller’s illustrations stood out.

Whenever we read a novel we have our internal interpretations of the story, the setting and the characters, and I found in Miller’s images the darkness and intensity I’d always enjoyed in Tolkien’s books. For example, his portrayal of Helm’s Deep conveyed the terrifying scale of the battle, especially the monstrous, remorseless power of Saruman’s army – the whole image is so alive, I felt as though I could hear the battle, the clashing of steel, the drums, the screams. As with all Miller’s work, it boasts incredible detail, bursting with energy, two of the malevolent characters almost staring at, challenging, the viewer. When writing my epic fantasy Tree of Life trilogy, I wrote several battle scenes and I always keep this image of Helm’s Deep in my mind when doing so.

Born in 1946 and educated at St Martin’s School of Art, Ian Miller became one of Britain’s foremost fantasy illustrators. Known for his distinctive Gothic style, Miller’s work is immediately recognisable, and although profoundly original, I detect hints of Hieronymus Bosch, Pieter Bruegel the Elder and Albrecht Dürer in his work. Miller has worked on many book covers, including editions of H.P. Lovecraft’s stories and the Fighting Fantasy gamebooks. He contributed to Ralph Bakshi’s animated films, most notably the memorable post-apocalyptic science fantasy Wizards, where his macabre, richly detailed backgrounds added real atmosphere and a sense of depth.

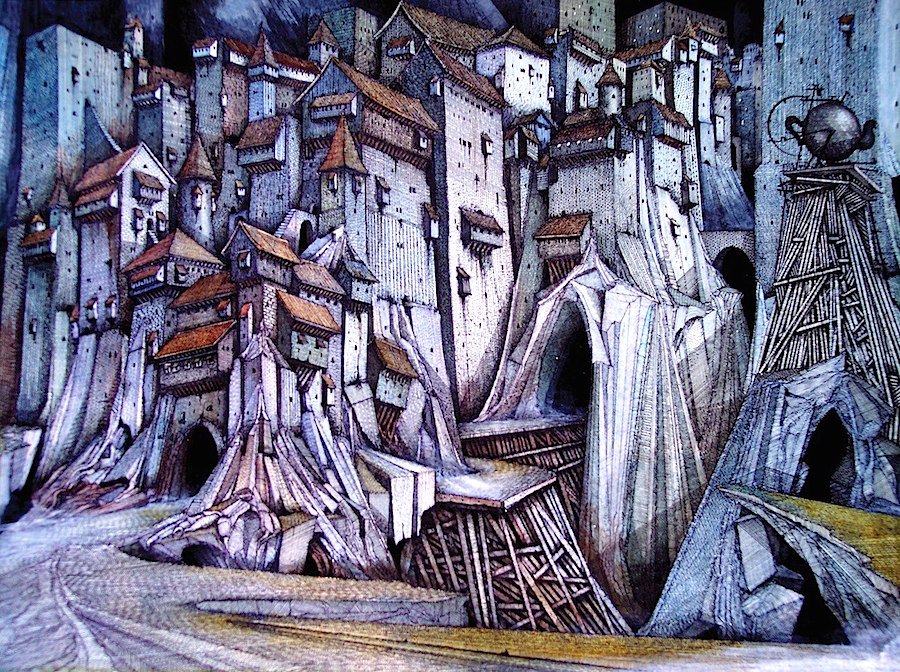

Miller also produced memorable illustrations inspired by Mervyn Peake’s classic series of Gormenghast books. Central to the story is the monstrous edifice of Gormenghast itself, whose ancient towers and mighty walls provide the ideal setting for the ritual-ridden people living there. Many of the characters inhabit the dank, damp corridors and rooms like ghosts, and the castle seems to be rotting and sinking. Through his dark, almost surreal style, Miller captures the slow decay of Gormenghast, hinting at the rising madness of the society within.

Miller once said:

“Rust, falling facades, tottering buttresses, and an overriding sense of impermanence, these are the things which fascinate me the most.” These objects of fascination coalesce in Miller’s Gormenghast illustrations, creating frightening but compelling visions that truly complement Peake’s Gothic masterpiece. The bold, often grotesque and nightmarish visions of Ian Miller lurk always somewhere in my imagination; whenever I write scenes set in forests full of gnarled trees or in crumbling buildings and edifices, I know they are in part inspired by Miller’s work. If you are interested in finding out more about Ian Miller, there is a collection of his artwork in the book ‘The Art of Ian Miller’, which showcases the sheer scale and depth of his creativity.

If you’re interested in my writing, you can get the ebook version of my first novel - The Map of the Known World – for FREE. Please see the following Kindle preview:

|

Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed