|

One of the joys of reading fantasy fiction is the opportunity to dive into and explore imaginary worlds. Well-crafted secondary worlds are not mere background – they enhance and enrich the story, and help shape the characters and themes. These worlds feel like living and breathing places, as if the author is using a real setting, describing lands and places they have actually visited. Such worlds seem to exist beyond the immediate narrative of the story; as a reader you can easily imagine other stories happening simultaneously, with other characters experiencing adventures and challenges of their own.

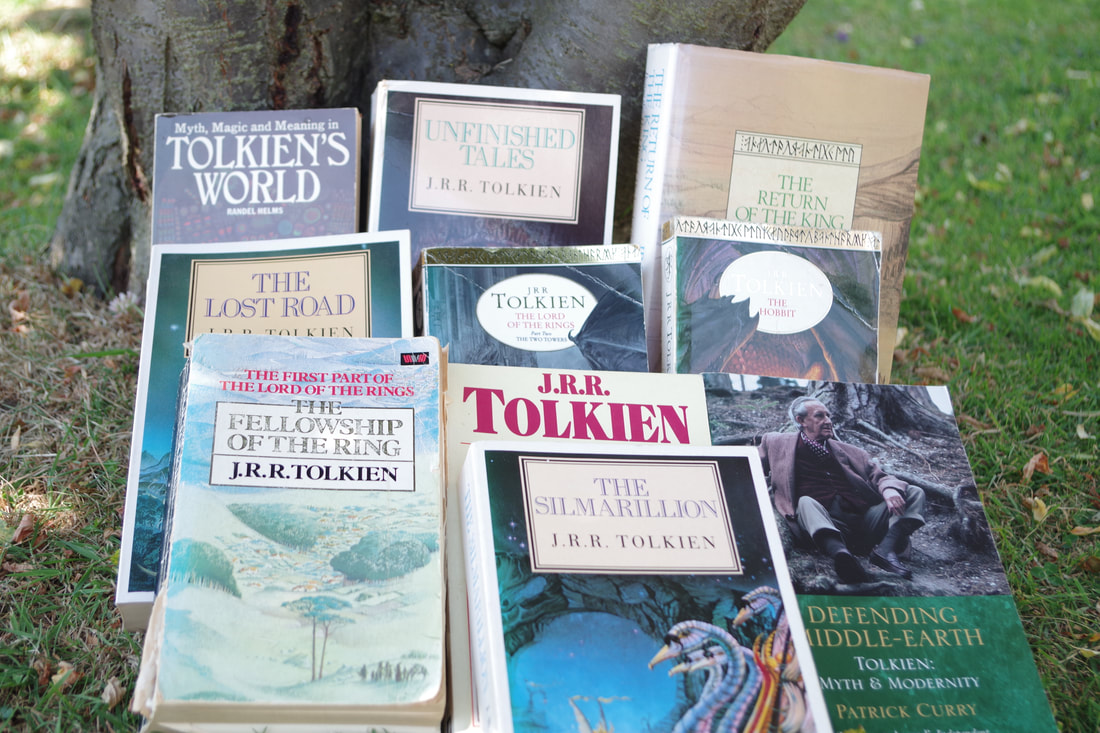

In this post I am going to discuss three of my favourite imaginary worlds – Middle-earth, Osten Ard and Gormenghast. Middle-earth I have posted previously about how the work of J.R.R Tolkien inspires my writing, and of all the secondary worlds in fantasy fiction, Middle-earth is the most famous and the most imitated, inspiring settings across the genre of epic fantasy. Tolkien described his world: “The theatre of my tale is this earth, the one in which we now live, but the historical period is imaginary. The action of the story takes place in the North-west of Middle-earth, equivalent in latitude to the coastline of Europe and the north shore of the Mediterranean.” Middle-earth is complex and coherent, drawn from deep pools of mythology, language, history and geography. Tolkien’s academic grounding in Anglo-Saxon, Celtic and Norse mythology helped shaped the landscape. The scale and depth of Tolkien’s creation is almost overwhelming: the characters, races, lands and legends. Readers have long pored over maps of Middle-earth, exploring places such as the peaceful, bucolic Shire, Rivendell, Gondor, Mirkwood and the bleak, desolate Mordor.

This is an ancient landscape, with a real sense of history; Middle-earth shows the effects of time, with the remnants of lost civilisations such as the Tower of Amon Sûl, the Barrow-downs and the Argonath. The natural world is always present – flora and fauna, the passing of the seasons, the night-sky, the sun and the moon. Despite the fantasy elements – the creatures, the sorcery – Middle-earth feels real and the characters endure real physical ordeals (hunger, thirst and exhaustion); the rules of nature are not ignored, and indeed serve to underpin and strengthen the fantastical parts of the story.

The story is deeply rooted in the landscape: Middle-earth is alive, an active character in Tolkien’s work. For example, when the Fellowship attempts the pass of Caradhras, they describe the mountain as though it was a character: Gimli looked up and shook his head. ‘Caradhras has not forgiven us,’ he said. ‘He has more snow yet to fling at us, if we go on. The sooner we go back and down the better.’ And think of the forests of Middle-earth, such as Fangorn, Mirkwood and the Old Forest – these are not generic woodlands but places with unique characteristics, and perils, of their own, and each serves to challenge the characters in Tolkien’s stories. This is not an inert landscape, just a passive resource to be plundered – Middle-earth reflects Tolkien’s profound ecological concerns and his respect, even reverence, for the natural world. And Middle-earth is a threatened world, whether through the malice of Sauron or from Saruman’s uncontrollable lust for technology and power. The words of Saruman retain a chilling resonance to our own world’s problems: "We can bide our time, we can keep our thoughts in our hearts, deploring maybe evils done by the way, but approving the high and ultimate purpose: Knowledge, Rule, Order; all the things that we have so far striven in vain to accomplish, hindered rather than helped by our weak or idle friends. There need not be, there would not be, any real change in our designs, only in our means." Saruman ruins his environment to serve his own purpose – he is indifferent to the damage he creates, he sees only his own needs and desires. In our world of growing man-made environmental catastrophe, this is something we can easily recognise. Tolkien’s work may have a reputation at times for being cosy and inward-looking, but he warns against the folly of unfettered greed and ambition, and shows that exploitation of our natural world can lead only to our own suffering, even destruction. Middle–earth forms part of the imaginative landscape of millions of readers, and continues to be an inspiration for writers, artists, filmmakers, musicians and environmentalists.

Osten Ard

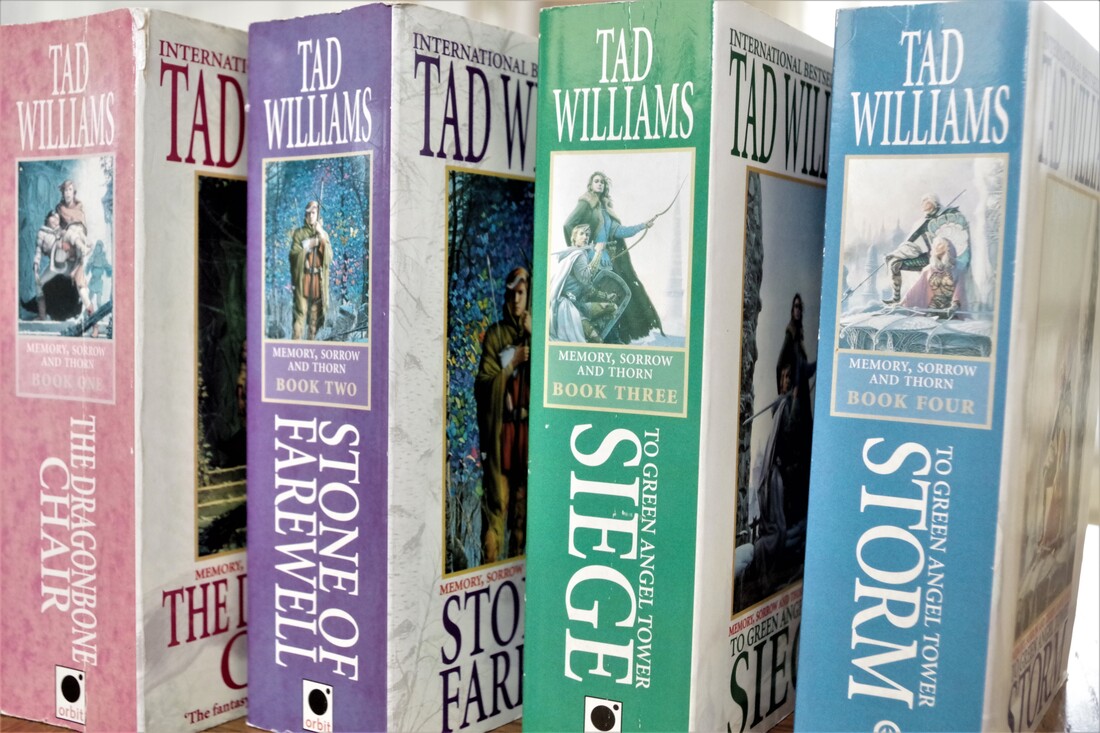

“Welcome stranger. The paths are treacherous today.” I first encountered the world of Osten Ard in Tad Williams’s landmark epic fantasy series Memory, Sorrow and Thorn – an influential work described by Locus magazine as ‘The fantasy equivalent of War and Peace.’ Superficially, Osten Ard resembles many Tolkien-inspired secondary worlds, with its medieval milieu, mountains, forests and swamps, but the Memory, Sorrow and Thorn series both uses and challenges many tropes and assumptions of the genre. There are few easy answers in Osten Ard, and do not expect simple separation into good and evil.

Memory, Sorrow and Thorn is a long read but never dry; written with wit, wisdom and intelligence, it is filled with excitement and memorable three-dimensional characters (Isgrimnur and Binabik are two of my favourites). And the world of Osten Ard – from the Wran to the Nornfells – plays an enormous role in the success of the story.

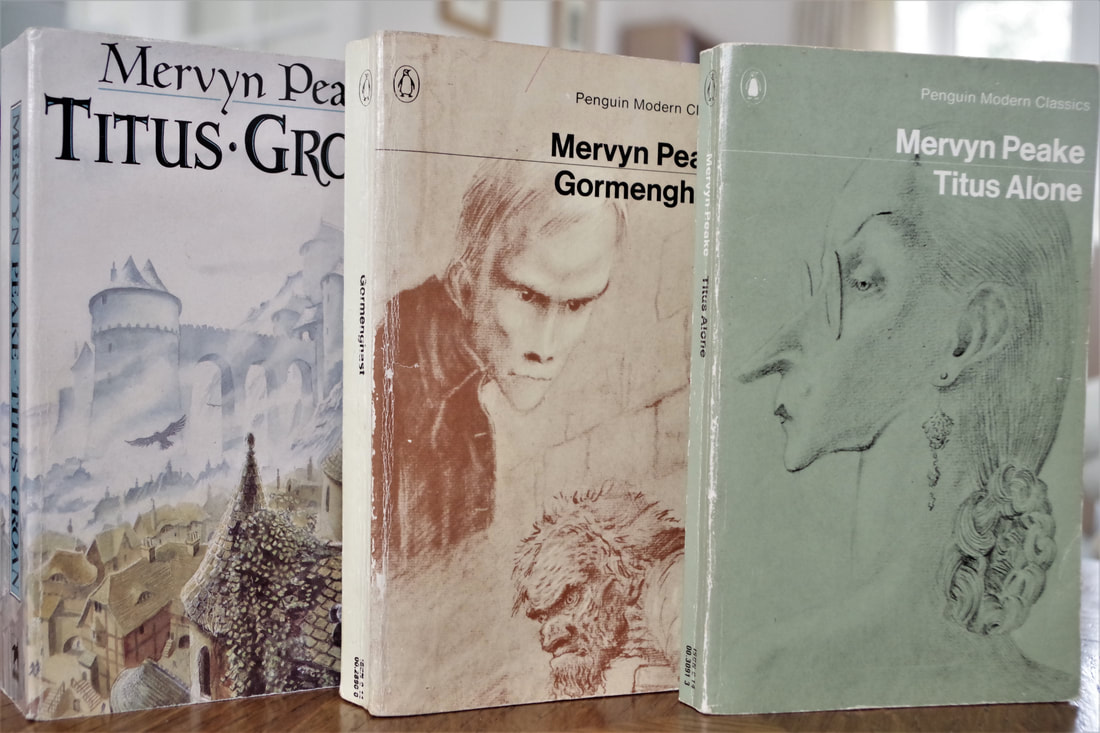

The depth and coherence of Osten Ard gives a strong foundation to the fantastical parts of the story, and in many cases reflects the psychology of the races and characters within. For me, the most fascinating part of Osten Ard is the fortress of the Hayholt. Doctor Morgenes describes it thus: “The Hayholt and its predecessors – the older citadels that lie buried beneath us – have stood here since the memories of mankind.” The Hayholt was formerly known as Asu'a, and was a city of the Sithi, the elf-like former rulers of Osten Ard, before it was besieged and captured by human invaders. The Hayholt is a haunted place, a place of secrets, with tunnels and caves beneath – it is not just a striking location, it symbolises suppressed human guilt over their genocidal war against the Sithi. This is typical of the complexity and ambiguity that lifts Osten Ard far above most secondary worlds in the genre. If you are yet to discover Memory, Sorrow and Thorn, then I recommend you make it your next fantasy read – the paths might be treacherous, but once you start exploring Osten Ard, you’ll find it a rewarding and absorbing journey. Gormenghast “Gormenghast, that is, the main massing of the original stone, taken by itself would have displayed a certain ponderous architectural quality were it possible to have ignored the circumstances of those mean dwellings that swarmed like an epidemic around its outer walls.” Sometimes lazily compared to the Lord of the Rings, Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast books (consisting of Titus Groan, Gormenghast and Titus Alone) resist easy description and classification: a fantasy, a scathing allegory of British life and society, a dystopian vision - whether the books are perhaps all these things or none, there can be no doubt they form a highly original work, dreamlike, layered and gothic. Central to the story is the monstrous edifice of Gormenghast itself; the ancient towers and mighty walls create a dense oppressive atmosphere, and an ideal setting for the madness of the ritual-ridden society trapped within. In less skilful hands, the dark architecture – the Stone Lanes, the Tower of Flints, the Great Kitchen – could have submerged the story, but instead through Peake’s witty prose, the setting adds elements both surreal and darkly comic.

The story is peopled by a carnival of eccentrics, such as the demonic cook Swelter, the cadaverous Mr Flay, Lord Sepulchrave (76th Earl of Groan), morose, exhausted, depressed by the endless demands of his role, and of course the murderous kitchen-boy Steerpike, the main driver of the narrative who schemes and slaughters his way to power. With life orchestrated by each day’s instructions from the Book of Ritual, many of the characters inhabit the dank, damp corridors and rooms of Gormenghast like ghosts. Yet, although the inhabitants of Gormenghast are larger than life, they have only too human foibles and failings such as greed, vanity and ambition. It is a fantasy but one uncomfortably close to our own lives; if we choose to look we can see our own weaknesses reflected.

Despite the eccentricities (though this is not a fantasy world of magic and dragons), Gormenghast feels so real, so tangible. When reading these books, I can almost smell the damp and mould, shiver in the cold rooms and passages, cower under the crumbling walls and towers of stone. Gormenghast itself, huge and malevolent, seems to be rotting, sinking, reflecting the corruption and empty ritual of its society. But while there is doubtless darkness in the Gormenghast books, a deep, suffocating darkness at times, one can also find kindness, humour, beauty and tragedy, all held together by Peake’s wit, psychological insight and vision. Which are your favourite fantasy worlds? Please leave a comment and join the conversation. If you’re interested in my writing, you can get the ebook version of my first novel - The Map of the Known World – for FREE. Please see the following Kindle preview:

1 Comment

|

Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed