|

Writing This Sacred Isle required a huge amount of research about Britain in the Sixth Century – from everyday elements such as food, clothes and weapons, to more abstract details such as mythology, social structure and religion. I needed to study Anglo-Saxon and Celtic cultures, as well as considering the marks left on the landscape and society by Roman rule. To carry out this research I visited key sites of interest such as West Stow and Sutton Hoo, as well as a host of museums, for example the British Museum and the Fitzwilliam Museum. Of course, the internet was also helpful in checking some specific points. However, in terms of research, nothing was more important, valuable or inspiring as the time I spent researching in my local library. It helped bring home to me why libraries matter to me, and why I believe they matter to the whole community. We live in a time when (certainly in the UK) many libraries are under threat of closure. They are an easy target when it comes to local authority budget cuts and many argue that they are just an anachronism, meaningless in today’s digital world, superseded by the benefits of the internet. I believe this is a mistake, and if we lose libraries, it will be to the great detriment of our community and cultural life.

At every stage of my life, I have received help from a library: exams, job interviews etc. And when it comes to book research, I have found my local library invaluable. Put simply, I could not have written any of my books (The Tree of Life trilogy also required considerable resource) without the use of a library. I could not have afforded to buy all the books I needed to consult for This Sacred Isle – this would have left gaps in my research and cut off vital sources of inspiration. However, thanks to my local library, I was able to spend hours poring over works such as the Anglo Saxon Chronicle and, Early Anglo-Saxon Burial sites and Blackwell’s encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. I found wonderful books about Pictish history, about Celtic mythology, and about the physical landscape of East Anglia, the setting for my story. Libraries give you that freedom: they allow you to experiment with your reading, try different things, investigate – it doesn’t cost you any money. It gives anyone a chance to learn, to discover, and to create. You can find your own path, rather than being guided by corporate motives. Many times I have stumbled across books within the library, books that have given me fresh inspiration and impetus. I remember whilst writing The Tree of Life trilogy finding an old, tattered book based on a medieval bestiary – the fantastical creatures and lurid tales I encountered within sparked off many ideas that helped me develop my plot. Such happy accidents can happen via internet research, but to me they’d be less organic, less meaningful. A good library gives you a quiet (sometime silent) place to think, an antidote to the immediacy and noise of much of our society. It is a neutral space; you are not being sold a product or service. I found an hour in a reference library really gets the creative juices going, and I wonder if it’s a combination of being in a contemplative place, with other people around (connecting me to the rhythm of society) and being surrounded by centuries of learning collected in hundreds, thousands of books. In my view research within a library moves an author away from a world of soundbites and disposable, wafer thin knowledge. Don’t mistake me – the internet is a wonderful tool, a gift for authors and our lives would be far more difficult without it. But on screen you are under the constant threat of disruption or interruption, be it emails, security updates, or the burning, nagging need to update twitter or clicking on YouTube to watch the latest trailer for a new movie (guilty as charged on this one). I like to think libraries are often full of people hoping, dreaming. How many of them have found knowledge, inspiration, entertainment or even solace within their local library? How many people, otherwise isolated, otherwise cut off from other people and a cultural life, can find some measure of fulfilment within the library? Yes, budgets are always tight and yes there are many worthy services that require investment, but I believe libraries are much more than just a place where people loan books; I believe they are a crucial part of our communities. Within the county I live in, I have seen libraries become hubs for local charities, social enterprises, and even start-up businesses, giving people a chance to connect, to learn new skills, to find new career paths. Authors, readers, indeed anyone who believes in the importance of community and culture should stand up for libraries - signing petitions, supporting online campaigns, fundraising etc. Libraries can change of course, must change sometimes, but I would argue it is essential they are preserved. A place of learning, a place to think, a refuge – the library are all these and much more. Let us not lose this gift of civilisation – our communities and our lives will be the poorer if we do. Why are libraries important to you? Add a comment and join the conversation.

2 Comments

After finishing my most recent novel, This Sacred Isle, I am working on my next book, a dystopian novel called Second Sun. Over two blog posts, I am looking at my favourite dystopian novels, and why they are important to me. In my first post, I looked at three classic works: We, Brave New World and Nineteen Eighty-Four. In this post, I am discussing two of my favourite reads: V for Vendetta and The Tripods. All these books - and others - are key inspirations for Second Sun. The Tripods - John Christopher Yes, this is an odd and possibly controversial choice, but I will explain myself! My introduction to The Tripods trilogy was via the BBC TV adaptation (sadly and hurriedly truncated after two series) but I soon dived into the books and what a rich experience they proved to be - not only a wonderful read but one of my inspirations for wanting to write novels. It was certainly an influence on my Tree of Life fantasy series. Strictly speaking, The Tripods is a post-apocalyptic SF novel rather than a dystopian one, but I think there are a number of key elements and themes that bring it within the dystopian realm. The story is set in the future, where the Earth has been conquered and humanity enslaved by the alien Masters who bestride the world in the Tripods, enormous three-legged walking machines. Human society has returned to a pastoral, pre-industrial level, with few towns – all monitored carefully by the watchful Tripods. Obedience to the alien conquerors is established through Caps, implants forced on every human at the age of fourteen. Once the Cap is implanted, humans lose curiosity and (most importantly to their rulers) any sense of rebelliousness. For a few, the Cap fails and they are turned into ‘Vagrants’, who are considered mad and wander from village to village, shunned by the populace. This is not a dystopia that uses consumer or sensual pleasures to lull and distract the people (like for example Brave New World), but the Tripods impose an orthodoxy, where people ‘know their place’, and to challenge this stability is to risk punishment or death. The hero of the book is thirteen year-old Will, an English boy, who is suspicious and fearful of the Tripods. With his ‘Capping Day’ approaching, Will flees with his cousin, Henry, to the ‘White Mountains’ in Switzerland. During their dangerous journey across France, they meet up with Jean-Paul, known to them as Beanpole. Beanpole is intelligent and inventive, and fears that Capping will steal his curiosity, and so he joins Will and Henry on their quest for freedom. During their subsequent adventures, they face danger not only from the Tripods (and the mysterious Masters who control the machines) but from adults who have been Capped. Capped humans never challenge or question the Tripods, who they believe only wish to protect them and stop them slipping into horrors of the past like disease, famine and war – they believe they live in a better world, not a dystopia. And I think this is a crucial point: the distinction between utopia and dystopia is sometimes found only in the eye of the beholder. The world as ruled by the Tripods is peaceful and humans live simple lives, and there are moments, certainly in the first instalment The White Mountains, where our rebellious heroes are tempted by the safe, easy life of the Capped. But the gifts of the Tripods come at a price: freedom. Humanity is imprisoned, with the Cap removing all capacity for challenging thought and creativity. Yes, this protects people from some of the worst excesses of our history, but in doing so it eliminates our innate curiosity, our imagination. The politics of our time is often shaped by a desire to return to simpler times, for a retreat from the complexity of the modern world – we have seen these in many of the arguments put forward in support of Brexit, Donald Trump and Marie Le Pen. In The Tripods, such a worldview is made literal; it is a society in stasis, with no desire or hope of progress. Of course, in the story the Cap is a crucial tool of control, but I wonder if the author hints at times that people actually prefer this life, and are happy to trade freedom for the safety and protection offered by their tyrannical rulers. Even if the Tripods had a genuine desire to protect and support humanity, this is still a dystopian society, and without giving the whole story away, it becomes evident that the alien conquerors have plans for Earth that are not entirely benevolent… The Tripods might be considered a minor work compared with the great dystopian novels, but as a young reader it started me thinking about questions of freedom and of the importance of challenging authority, even when (especially when) it conflicts with the entrenched views of those around you. This is made clear early in The White Mountains when Will thinks fearfully about his impending Capping Day: “Only lately, as one could begin to count the months remaining, had there been any doubts in my mind; and the doubts had been ill-formed and difficult to sustain the weight of adult assurance.” To escape the imprisonment of the Cap, Will must defy his family, friends, teachers and village elders – it is his courage in opposing all the people he has grown up with that marks him as a hero in the making. The society ruled by the Tripods is one of total obedience and Will cannot, even among friends and family, safely voice his concerns. And this for me is one of the fundamental lessons of any dystopian novel: a worthwhile society should expect, accept and absorb criticism, and any society that crushes dissenting voices is well on the road to tyranny. The Tripods is undoubtedly an exciting story for young adults, with adventure and action aplenty. But its messages about freedom, and the need to find the courage to oppose orthodoxy, still resonate. I would argue freedom, questioning authority and the desire to travel are all human rights, and in this book all are denied by the alien rulers. We must be careful not to allow our own rulers to fool us into trading these precious rights for a feeling of safety from outsiders. And, without giving away the ending, the trilogy finishes on something of a melancholy note, one that has always stayed with me. Suffice to say, humanity does not need aliens to cause strife and division in this world… V for Vendetta - Alan Moore / David Lloyd I came relatively late to the world of comics / graphic novels, and through reading works such as Maus and Persepolis, I swiftly realised I had been missing out! And one book that stood out for me was V for Vendetta – a powerful, savage indictment of right-wing power, inspired by the Thatcherite government in Britain. The story depicts a near-future history version of the United Kingdom in the 1990s. A nuclear war has destroyed much of the rest of the world, and although the UK avoids being bombed (the government of the day having removed American missiles) it suffers from the environmental and economic chaos resulting from the conflict. As a broken and heavily flooded UK starts to fall apart, the Norsefire party (consisting of fascist groups and the few remaining corporations) seize control and promise to restore order, which they do by exterminating opponents and implementing a police state. The protagonist, V, an anarchist dressed in a Guy Fawkes mask, begins a campaign to both kill his former captors and bring down the brutal Norsefire regime. His actions ultimately inspire Evey Hammond, a young woman he saves in the opening scene of the story, to become his protégé. Evey begins the story as a victim at the hands of ‘The Finger’, the secret police, but soon finds her strength and realises the importance of V’s campaign. As well as being a compelling story with rich, complex characters, V for Vendetta challenges the reader to consider the causes and effects of poor government, and our own weak record in selecting our leaders. As V rallies against Norsefire, he highlights the culpability of the wider population:

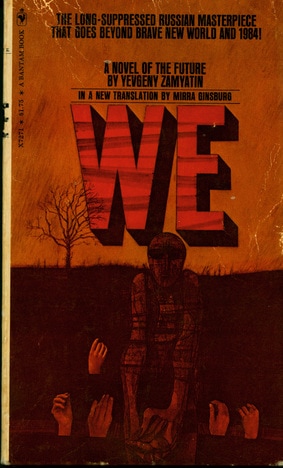

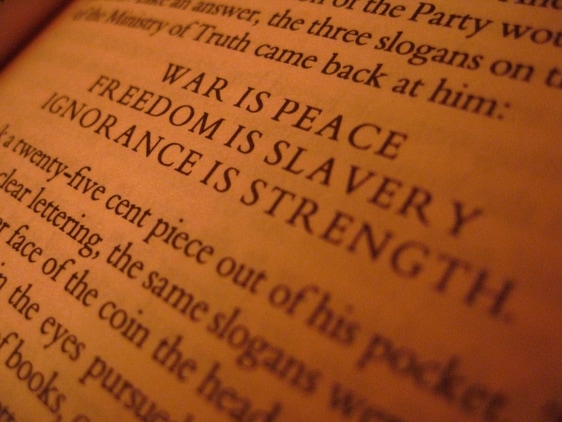

“We’ve had a string of embezzlers, frauds, liars and lunatics making a string of catastrophic decisions. This is plain fact. But who elected them? It was you! You who appointed these people! You who gave them the power to make your decisions for you!” V is highlighting how our collective apathy, our willingness to pass on responsibility to others (however unsuitable) leads us slowly but inexorably to tyranny. We can be the makers of our own dystopia. The Norsefire government gained control because they made enough people feel safe in a chaotic time, and for this safety the people were prepared to give up their freedom and to turn a blind eye to the suffering of minorities, who were made scapegoats for problems facing the country. Tyranny rules because the population stepped back from responsibility, and to bring back any sense of justice, the citizens of the story must stand up against Norsefire. As Evey Hammond proclaims near the end of the story: “You must choose what comes next. Lives of our own, or a return to chains.” Reading V for Vendetta again recently, in the context of recent political developments, it still feels horribly relevant. The rise of right-wing governments, the demonization of minorities, the bombardment of ‘news’ – sometimes it almost feels as if a real-life Norsefire are just waiting in the wings, ready for the right moment to seize power. In the opening panes of the story we see surveillance cameras – there FOR YOUR PROTECTION of course. We are being watched. England Prevails… Dystopian novels dare to imagine where the worst of our natures and weaknesses could take us – they show the traps that wait to snare us. I believe all five stories I have discussed in these posts help us to go forward with our eyes open and not sleepwalk into horrors of our own making. Which dystopian books do you find most powerful? Add a comment and join the conversation. During the writing of This Sacred Isle, I realised it is in some ways a post-apocalyptic novel, as well as being an historical fantasy. The world of 6th century Britain existed within the bones of a fallen civilisation - Roman Britannia. This allowed me to explore within the book themes of identity and freedom, themes I will continue into my next novel, a dystopian SF novel called Second Sun. I have long been fascinated by dystopian novels and – with recent world events in mind - such books are very much in focus. I believe dystopian novels, certainly the best ones, hold a mirror up to our own world, allowing us to see dangers we can easily ignore; sometimes those dangers will be amplified within fictional words, but this only serves to make the warnings they possess more stark and pressing. Across two posts I am going to look at my favourite dystopian novels, and why they are important to me. This first post will look at three classic dystopian novels: We, Brave New World and 1984. We - Yevgeny Zamyatin We, by Russian novelist Yevgeny Zamyatin, in many ways set the template for the modern political dystopia. Set in the twenty-sixth century AD, We is narrated by D-503, a spacecraft engineer, who dwells in OneState, a city state where the programmed society is organised by strict logic and mathematical formulas. The story occurs long after the Two Hundred Years’ War – an enormously destructive conflict that wiped out the vast majority of humanity. OneState is surrounded by the Green Wall, which separates the citizens from the untamed nature beyond. The natural world is viewed with horror (OneState’s people eat food made from petroleum) and D-503 considers it ugly when compared to the manufactured environment in which he lives. In this world of glass buildings, there is little or no privacy (blinds only come down during the discreetly named Personal Hour) – it is a life lived on show, in public view. Peace and happiness are achieved at the price of a private life. Happiness comes through lives being controlled – freewill and choice are deemed dangerous and root causes of human misery. Indeed, at the start of the book D-503 is happy, he believes in the system. Opponents of OneState are even called ‘enemies of happiness’. I find OneState’s obsession with happiness a deeply resonant theme. In our society much emphasis is placed on the search for happiness, to the point where feeling unhappy (aside from conditions such as depression and anxiety) is almost seen as wrong, abnormal. But what, in our modern world, do we really mean when we talk of happiness – is it a feeling of deep contentment and satisfaction or does it mean empty pleasures offering an easy escape from reality and hardships? The citizens of OneState are lulled by comfort and ease – they choose not to see the tyranny around them or at least believe the oppression is worth the loss of freedom. This is an uncomfortable theme, for it is only through a sense of discontent, of wanting to change aspects of society that we challenge and overcome injustice. The citizens of OneState, who have numbers not names, are not individuals – just replaceable, forgettable cogs in the machine. With their lives ruled by ‘The Table’, human relationships and interactions are reduced to scheduled moments (such as the aforementioned Personal Hour) and spontaneity effectively outlawed. As a result, there is an entrenched absence of feelings – for example, consider the lack of pity, as D-503 recounts when some unfortunate colleagues are incinerated in a work accident: “I’m proud to note down here that this did not cause a second’s hitch in the rhythm of our work, no one flinched.” These cold, dispassionate words must be a warning to us, a warning that we must see our fellow human beings as individuals, with worth and rights, for if we do not, we risk further embedding misery and injustice within our own society. We is not an easy read and the tortured, turbulent mind of D-503 can be a confusing place – and I suspect there are levels of symbolic, philosophical and religious imagery and themes within the novel that would require multiple readings to begin to comprehend. But the book is worth the effort and We unquestionably laid key narrative and thematic foundations for many dystopian novels to follow. Brave New World - Aldous Huxley Brave New World is often heralded as one of the most influential and prophetical books of the twentieth century. Set in the far future, the World Controllers of the story have created a perfect world, using genetic science - every individual receives pre-natal / post-natal conditioning so as to accept his or her position in society, from the Alpha-Plus ruling class to the Epsilon-Minus Semi-Morons who are bred to perform menial tasks. This society is perfectly ordered, and control is strengthened through the habitual, state-endorsed, use of the drug soma, and other distractions such as ‘feelies’, a kind of proto Virtual Reality. In many senses, the people of the novel are controlled by pleasure and enjoyable distractions (a thematic link to We); when life is so good and so easy, why even think to challenge the status quo, what would be the purpose? This is not a tyranny of brutal physical oppression but a tyranny in which the citizens are imprisoned in a gilded-cage of amusement and ease. The World Controllers of Brave New World have perfected a society where the genetically bred humans have their basic needs of comfort, sex, food and pleasure met in abundance – in this state opposition, freethinking becomes irrelevant, or worse a danger to the blissful lives of the citizens. Bernard Marx is unhappy for he desires solitude and is disgusted by the endless pleasures of his society – he struggles to understand his discontent with the world, a feeling I think many of us would recognise. Bernard is a misfit – he is smaller than the other Alphas and his individualism places him in danger of exile. He does not meet the norms imposed by his society and thus is viewed with suspicion. When I first read Brave New World many years ago I was impressed by its brilliant invention and wit, but as time passes, I view the book with wonder at the continuing relevance of many of the concerns Huxley explored in his novel. Considering the rapid advances in technology in our own world, Brave New World simply becomes more relevant. It is increasingly possible to live a life in the virtual world, where you can in effect become another person, whoever you choose to be – submerged in such a pleasurable and stress-free life would you even care or notice that you are living in a dystopian world? Nineteen Eighty-Four - George Orwell When I first read Nineteen Eighty-Four I felt as though I had stepped inside a nightmare. Airstrip-One is a crucible of relentless pressure – I could scarcely comprehend the horror of the constant surveillance, the crushing conformity, the lingering danger of arrest and the sheer misery: horrible food, the bitter cold and the dilapidated living conditions. It is a wretched world, mutilated by an endless three-sided war – anger and sexual frustration are channelled into hatred towards enemies of the state real and imaginary. The most memorable display of this is the Two Minute Hate, where the Party Members are whipped into a frenzy of hatred.

“The horrible thing about the Two Minutes Hate was not that one was obliged to act a part, but that it was impossible to avoid joining in. Within thirty seconds any pretence was always unnecessary. A hideous ecstasy of fear and vindictiveness, a desire to kill, to torture, to smash faces in with a sledgehammer, seemed to flow through the whole group of people like an electric current, turning one even against one’s will into a grimacing, screaming lunatic.” So much of the language of Nineteen Eighty-Four has become part of our everyday idiom: Room 101, Big Brother, doublethink, thoughtcrime, Newspeak to use just a few examples. In some ways, such common use (often in trivial contexts) has diluted the power of these concepts; only when read as part of the actual book is their true power, and horror, revealed. For although this is a book with profound comments on politics and society, it is above all a book with a very human focus. We see Winston Smith’s suffering not just in existential terms, but in everyday terms: his blunt razors, the crumbling cigarettes, his coughing fits and varicose ulcers. Such a human perspective makes the horrors of Airstrip-One even more striking; we see how the oppression and privations take their toll on the citizens. We witness the misery and loneliness of an individual crushed and dehumanized by the tools of political terror. So what does Nineteen Eighty-Four say to us about our own world? While Big Brother style totalitarian states still exist, I would argue that the form of political control postulated by We and Brave New World – control through distraction – is closer to how Western society has developed. However, such methods are also evident in Nineteen Eighty-Four, especially in relation to the downtrodden proles, who are distracted from political involvement by mass entertainment, a dubious National Lottery and sport (and, where necessary, the iron fist of state security). The phenomenon of a constant bombardment of dubious ‘news’ is one we are increasingly familiar with and although we do not have telescreens watching our every move, we have CCTV monitors aplenty and the potent for tracking through phones and other devices. We may not be in Airstrip-One, but some of the parallels are a little uncomfortable. And it is difficult to read Winston Smith’s diary entry about his visit to the cinema, as he describes a film in which ships full of refugees are bombed in the Mediterranean – the audience laugh at the suffering of the refugees as they are bombed and drown. It seems horrific, unimaginable to be entertained by such images, but in affluent Western Europe do we not turn aside with indifference as refugees, children and adult alike, drown in the very same sea Orwell described, and show little compassion or concern, our emotions blunted by saturation on TV and the internet? Others may disagree – and they have the right to do so – but for me this is just one example where Orwell shows us the callousness of which people, all people, are capable, and we would be wise to take heed and consider our own responses. I cannot overstate the importance Nineteen Eighty-Four has for me. Reading it first as a teenager, it changed how I thought about books, society and politics. Even now, the book still burns with fury and although it cannot accurately be called a prophecy, Orwell’s book is a warning, one I believe will endure through the ages. In conclusion, all these books rally against orthodoxy and comfortable, unquestioning conformity. They challenge us – they hold up a mirror and when we look, if we choose to look, we see our worst side staring back. These books say we have to think better, we have to act better to avoid slipping into the nightmares they so chillingly describe. In the next post, I will look at two more, very different, dystopian books. Which dystopian books do you find most powerful? Add a comment and join the conversation. |

Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed