|

You’ve put your heart and soul into your trilogy; you’ve forged worlds, invented characters and shaped a compelling narrative. Over three novels you’ve built intrigue and suspense – you’ve hooked the reader but how do you make sure your story finishes strongly?

In this final post of my three-part blog series covering lessons I learned from writing The Tree of Life, I am going to discuss how to bring your trilogy to a satisfying conclusion. I will risk a few borderline spoilers about my books, but certainly won’t give away the actual ending! The lessons I learned helped not only my trilogy but also my most recent novel, This Sacred Isle, and I hope these posts offer some helpful and applicable advice to anyone undertaking the task of writing a three-book series. Of course, a successful ending is important in any book, but the significance is magnified within a trilogy. In my experience planning is crucial, both to sustain the narrative drive and avoid inconsistency – (check out my first post in this series, which covers planning in detail). By the third book, you will have a mass of characters, events, settings and backstory; to control this you must plan ahead to make sure you don’t leave plot threads dangling.

But beyond planning, I believe there are three significant danger areas when ending a trilogy, three traps you should strive to avoid:

Don’t slow your third book down with too much back story You will have already covered a lot of material in books one and two, so much so that it’s tempting to rerun over some of that back story just to make sure your reader can be fully orientated within the story. But you must tread carefully. The third book needs to have strong momentum, moving towards a denouement. Of course you will still need exposition, but do not bog down your third instalment covering ground already established in the first two books. Your reader cannot be expected to remember all relevant details from books one and two, but neither will they have forgotten everything and they will not appreciate reading about elements they have already covered. When writing The Last Days, I worried constantly about how much I should refer to past events within the story as prompts and ‘reminders’ for readers – however, I soon discovered these bogged down the book’s pace, right at the time when I wanted the story’s excitement to be building to the highest pitch. As I continued to edit the book, I resolved to include as little back story as possible, especially in the final stretches of the novel - this allowed the story to breathe and (I hope) helped to make the book a more absorbing and thrilling read. So, my advice is to keep back story to a minimum and keep progressing towards the end. Know when to stop – do not keep going on, and on, and on… I worked on The Tree of Life trilogy over the course of twelve years, and the characters of Elowen, Bo, Black Francis and many others became so familiar to me, it was a little difficult to finish the story and say farewell to them! But this is dangerous territory. . . When you have created so many characters and such a detailed narrative, it is tempting in the latter, climatic stages of the third book to keep extending the story, to keep exploring new facets and add fascinating new details. This is a temptation that must be resisted! You must not allow your trilogy to overstay its welcome; don’t allow your story just to fizzle out. Finish on a high note by all means, but make sure you do finish – leave your reader wanting more, not hoping for the end to come. Do not pluck a convenient ending out of thin air As I worked on The Last Days, I found that fiction fatigue set in – although I had already worked out the climax of the story, actually achieving this (i.e. making sure the characters acted and reacted in ways true to their inner and outer journeys, and that the resolution worked in emotional and narrative terms) felt like a heavy burden. At this point, it is easy to look for convenient ways to simplify your ending but this is potentially a huge mistake. You’ve established the context of your story, the rules, the personalities, all the ingredients and momentum for a successful ending. Take your ending from your characters and the conflicts described to that point; it must reflect the way the key characters have developed and the lessons they have learned about themselves – their choices must shape the conclusion. The climax of your trilogy could be happy or sad (or somewhere in between) but it must solve the central problem or question of your story, and it must be solved by your central character or characters. Ideally, the way the story is resolved must have some resonance, with the choices made by the characters reflecting the themes of the trilogy – there is no need to be heavy handed or preachy, but the reader should be left with a sense of a universal truth having been expressed. For The Last Days, I knew it was important for Elowen and Bo to understand what was at stake, and to understand that for good to prevail, sacrifice was needed. They are both tested, both offered power – it is how they react to this and the decisions they make, that is important and that drives the story to its conclusion. Remember: the protagonist of the story must be protagonist of the ending, i.e. what he or she does determines the ending. An ending can be unexpected – a shock even – but it must arise legitimately from the story itself. Throwing in something random at the end will shatter the rules of the world you have created and infuriate your reader. And one last point: when you have finished your trilogy, take a moment to savour the feeling. It is an achievement, so allow yourself to recognise and enjoy this! I wish you the very best with your epic fantasy trilogy and I hope readers enjoy reading about the worlds you create. Takeaway tip: the conclusion of your trilogy must be a reasonable and logical development from the story and characters you have written. Do not shortchange your readers with a random, incoherent ending. Check out of the other posts in this blog series: Part 1 looks at planning Part 2 looks at world building and research The Tree of Life trilogy is now available as an ebook boxset for just £1.99 / $2.40 (each of the volumes is also available individually in both paperback and ebook format): UK Amazon US Amazon See preview below:

Are you working on a trilogy or series? How did you write the ending - and what have been the major challenges you've faced? Add a comment and join the conversation.

5 Comments

In this second part of my three part blog series, I will be looking at what I learned about worldbuilding from writing my epic fantasy series - The Tree of Life.

In common with many epic fantasy trilogies, The Tree of Life is set within a secondary world. ‘Worldbuilding’ is often a key element of fantasy literature and a daunting challenge when about to embark upon a trilogy. Some authors create their secondary world in great detail (Tolkien obviously being the most famous example), inventing languages and histories, devising complex genealogies and drawing maps. There are stories where this is absolutely a valid approach, provided this background information does not swamp the actual book; it should only be added in small amounts to support the story. And the other great danger is this: world-building is fun, great fun – you are playing god – but it should not be done at the expense of actually writing your book. It is easy to fall into this trap; when I began work on my trilogy I turned immediately to worldbuilding. This did not extend to the creation of new languages etc. though I certainly did compile maps to help orientate myself within the story, plotted the main cultures (with information on their worldview, customs, beliefs and technology) and I worked out an historical timeline listing major events and turning points. I enjoyed this process immensely and it is easy to absorb oneself within the joy of what Tolkien memorably called sub-creation. However, as I filled notebooks with ideas and notes, the realisation dawned that I had done little to actually progress the story – I was staying within the gilded cage of world-building, and although this work was necessary, I could not delay writing the book. I needed to get on with planning and writing my trilogy.

Building a consistent setting

Your fantastical setting can be as bold, imaginative and wild as you can possibly make it but it must possess an internal logic, it must be consistent. You are free to set whatever internal rules you like within your secondary world, but you must then adhere to them, otherwise your creation will seem random, fragmented. And the settings you create must impact on your characters (and on occasions, vice versa) – we are influenced by our environments and this must be reflected by your fictional cast in their attitudes and behaviour. So, how to achieve this? Well, there are as many techniques as there writers, but for me, I always wanted my fictional world to echo our world, and decided early on that all the lands within the book should resonant with certain times and places in our history. As I think there are links and shared symbols between cultures in our world – however distant – I felt that drawing on real time periods and civilisations would give my setting stronger foundations, hinting at connections between the different realms and peoples. This helps create the sense that there is consistency in the world, that the various cultures have been shaped, for both good and ill, by contact with others. For example, Helagan, where the hero of the trilogy, Elowen Aubyn, lives and much of the action of The Map of the Known World takes place, is heavily influenced by early 17th century England, with a comparable level of technology and social structure. Why did I choose this period? I wanted the story to take place in a world on the cusp of modernity, with the first shoots of industrialisation appearing and the power of magic, of the Eldar races, beginning to fade – this would underpin much of the conflict and tension within the story. And one last point in achieving a consistent setting: I would leave areas of your invented world unvisited and unexplored. However big and sprawling your trilogy, is it really plausible that your narrative will venture into every corner of the world? Much better to leave whole regions to the imagination of the reader – make reference to those unexplored lands (for example, in The Map of the Known World I made mentioned to the Firelands, a mining, proto-industrial part of Helagan, but did not bring the characters there), but consider them as the sort of references we make every day of our lives to places we know about but are highly unlikely to visit. This somehow feels more real, suggesting that the world you have created exists beyond the limits of your specific story. Know your world - research If you want your world-building to be convincing, then you have to know your world, and in my case, to know my world meant I had to research. To use again the example of Elowen’s homeland of Helagan, I researched early modern England in great detail and used this information to establish features such as clothes, food and weapons – I believe this gives the world a more authentic feel. Where possible, I visited locations analogous to those I was creating in the book, such as St Michael’s Mount in Cornwall and Wastwater in Cumbria, and this allowed me to bring a greater sense of place to my descriptions of the settings. I continued this approach when I wrote my latest novel, This Sacred Isle, a book in which a sense of place was of fundamental importance. I developed other cultures within the trilogy in a similar manner, using, for example, researching in detail elements of medieval Russian, Mongol, Japanese, Ancient Greek and Assyrian history. I read books on these and other subjects, and visited many museums and galleries to immerse myself in the art and artefacts of these people and time periods. Adding specific details gives more authenticity to the secondary world and strengthens the credibility of the cultures being described, as it hints at their history in artistic, religious and technological terms.

Of course, I was writing a fantasy novel, not an historical novel, so I allowed myself significant latitude to twist my invented cultures into different directions, but I always used my research as the sound bedrock on which to build. And as much as I enjoyed researching the books (I love visiting museums and reading interesting non-fiction!), I was careful not allow research to eat all of my available writing time. For all the research in the world means nothing if the story itself remains unwritten…

Make the setting personal One last thing to remember: the world you create is your world. Of course, you should bring into that world a host of factual information drawn from your research, but for your creation to really resonant, it has to be meaningful to you. Think about the great secondary worlds created in fantasy literature - such as J.R.R. Tolkien's Middle-Earth, Stephen Donaldson's The Land and J.K. Rowling's Wizarding World; these worlds reflect the passions and concerns of their authors in profound ways. For my Tree of Life trilogy, I wanted to explore issues relating to prejudice, abuse of power and the destruction of the natural world – these issues shaped my secondary world as well as the plot and the characters. Think about the themes and issues that inspire you, and allow these to drive how you design your world. Takeaway tip: Worldbuilding is important but do not concentrate on this at the expense of getting your books written. And make sure your invented world is consistent and feels authentic – where possible research real world cultures etc. that echo your creation. The first part of this blog series can be read here. Look out for the third part of the series, coming soon. The Tree of Life trilogy is now available as an ebook boxset for just £1.99 / $2.40 (each of the volumes is also available individually in both paperback and ebook format). See links and a preview below: UK Amazon US Amazon

Are you working on a trilogy or series? How are you building your secondary world? Add a comment and join the conversation.

I have always loved reading and writing stories, and ever since devouring The Lord of the Rings as a teenager, I wanted to write an epic fantasy trilogy, a wish enhanced by reading other wonderful series such as His Dark Materials by Philip Pullman and Memory, Sorrow and Thorn by Tad Williams.

Over a period of some twelve years between 2000 and 2012 (and much hard work), I achieved my ambition and completed The Tree of Life trilogy, which I have recently republished.

The Tree of Life is a big, epic fantasy series - here is the blurb:

The Known World is dominated by the Mother Church and its sinister leader, Prester John. The Mother Church demands total loyalty - disobedience is punished by death. But in the darkest of times, comes hope… Fourteen-year-old Elowen Aubyn lives a miserable life in an orphanage. Bullied and lonely, she dreams of escape and adventure, little realising her dreams are about to come terrifyingly real. When the mysterious Tom Hickathrift gives Elowen an ancient map, she is plunged into a desperate and deadly quest - to discover the Four Mysteries, ancient artefacts of great power. Elowen must overcome many perils and defeat the greatest of evils, for if she fails, the only chance of freedom will be lost, forever... These books will always be close to my heart and allowed me to write about themes such as racial and religious intolerance, and the destruction of the natural world, all within a vast, exciting fantasy adventure. I also wanted to move away from some of the tropes of fantasy and introduce some unique settings rather than just a standard Medieval style world - the Known World is a land of monsters and muskets! And once published, it was wonderful to hear from readers who found the books entertaining too – the icing on the cake! It was a long writing journey starting from, bar a few short stories under my belt, being a novice author to one with the experience of having written three books – along the way I learned a lot about the craft of writing, and the demands of creating a trilogy. So, in a series of three posts, I will pass on the most important lessons I learned from The Tree of Life trilogy. This first post in this series will focus on planning. Planning When I began writing the trilogy I was very sceptical about the benefits of detailed planning. I worried it would be too restrictive, that it would hinder my creativity – I preferred to let the story and the characters emerge as I wrote. This approach seemed to work for the first volume of the trilogy, The Map of the Known World, which had a clear narrative structure. I was at the start of the journey and not burdened with immediate concerns of how to complete the full tale - the possibilities seemed limitless and exciting. I knew where I wanted the overall story to go (i.e. I knew the major plot developments and how it all finished) but I had not planned out a detailed roadmap and at this stage did not think it necessary. However, I hit problems as soon as I commenced the second part of the trilogy, The Ordeal of Fire. I did not have a shortage of ideas, but Elowen’s continuing journey introduced further characters and settings, and I started to feel lost and confused. It was a difficult time and I began to wonder how I could ever solve all the narrative problems I had written myself into! With mounting concern, I realised I could no longer write blithely, secure in the knowledge that the story was in its early stages – The Ordeal of Fire is the second act of the trilogy and I needed focus, I needed structure, I needed to plan. So I began by reading back through The Map of the Known World, picking up important elements I needed to carry through the rest of the trilogy. I worked out in more detail where I wanted the story to go, and the fates of the various characters. For The Ordeal of Fire, my planning took the form of an outline and character notes. However, when I came to write the final instalment, The Last Days, I went to much greater lengths. After initial brainstorming, I worked out a plot plan for the book, which I then fleshed out into a ‘treatment’, a document of some 10,000+ words covering the main beats of each chapter of the book, along with snatches of dialogue and notes about theme, imagery and character development. When I came to write the first draft of The Last Days, this ‘treatment’ was invaluable, a reassuring companion, giving me confidence that I knew exactly where I was going and (more or less) how I was going to get there! So I discovered planning did not restrict my creativity; on the contrary, it freed me from the confusing tangle of plots, subplots, characters and half-shaped ideas whirling around my head. Planning across multiple books also helps to achieve a greater consistency in voice and tone, which is important as you want readers to feel they are reading one coherent story. And talking of consistency, writing about characters across three books increases the chances of continuity errors - make sure you log key details about your characters (physical description etc.) and carefully check these when you edit each draft. It is easy to slip up and change, for example, a character's hair colour without noticing. If these errors slip through to a published version, readers will notice and it undermines your credibility. Of course, your editor can help spot these kind of errors, but don't leave it all to them - check and double-check. In conclusion, did I learn my lesson about planning? Absolutely. I would never embark on any novel, let alone a trilogy, without detailed planning. Taking planning seriously has, I believe, improved my writing skills and understanding of the craft, and I applied the same concepts and techniques when working on my latest novel, This Sacred Isle. Planning is hard work and it can be frustrating when you just want to get on with writing your story, but take a deep breath and step back - your book will be better for it. Takeaway tip: writing a trilogy is a huge project, so do not underestimate the difficulty of managing a high number of characters and subplots. Spending time on planning might feel like a waste of time but in the long term it will save you time and give you greater consistency and clarity of vision. Check out the second part of this blog series, which examines world building and research. The Tree of Life trilogy is now available as an ebook boxset for just £1.99 / $2.40 (each of the volumes is also available individually in both paperback and ebook format): UK Amazon US Amazon See preview below:

Are you working on a trilogy or series? How do you plan - and what have been the major challenges you've faced? Add a comment and join the conversation.

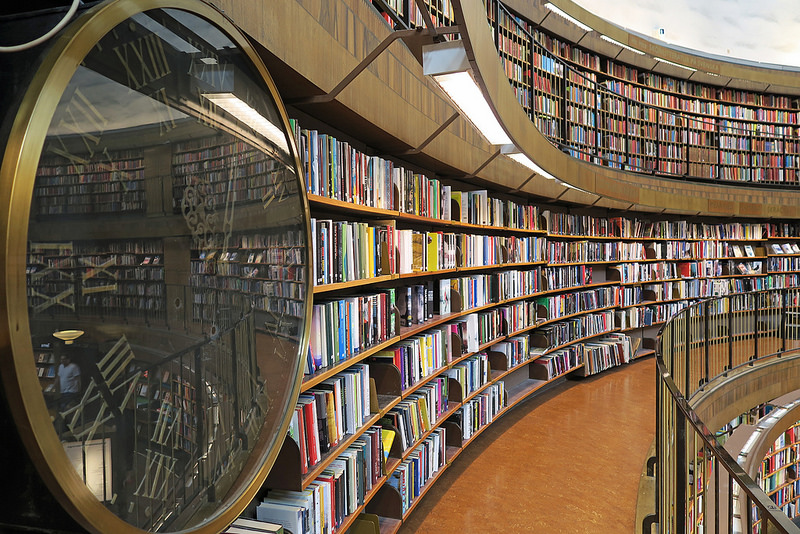

Most authors, perhaps all authors, work in fear of writer’s block – that horrible time when your ideas stop, and your prose feels flat and lifeless. You experience less joy in writing and it seems as though your imagination has dried up – you struggle to form pictures in your mind, and when you do those pictures lack sparkle and originality. Having completed four novels, I talk from experience of this subject, and so I thought I'd share a few observations about writer's block and hopefully offer a few possible cures. What causes writer’s block? I guess there are many causes, but some of the most common are: Fear It’s hard to put your work out there for everyone to read. Writing expresses something of your inner self: your fears, your desires, your worldview. This can make you feel vulnerable, worried about how people will react when they read your book. Writing a book is deeply personal and when someone criticizes your work, it is easy to frame it as criticism of you as a person. A natural defence mechanism quicks in and the thought of writing something, let alone sharing it, becomes a huge barrier to creativity. Perfectionism This is linked to fear. You worry any prose less than perfect will expose you to scorn and criticism. To protect yourself, everything has to be right, everything has to be perfect. But this becomes a trap, a trap that prevents you from expressing yourself, a trap that locks-in your creativity. Outside pressure No one can write in a vacuum and other factors understandably have an impact: family commitments, work pressures, illnesses. All these (and many others) can reduce the amount of time and energy you have for writing. Writing a novel demands concentration and imagination over an extended period of time, and working with outside pressures pounding down upon you can make the whole project seem overwhelming, even impossible. So, those are the causes of writer’s block, but what are the cures? Based on my experience, I would suggest the following: Get moving Writer’s block saps your energy and imagination. So, to push through, you might need to take a break and leave your story for a while. If you can, go for a walk; I find this helps me tremendously, as the motion of walking frees my mind. Don’t put undue pressure on yourself. Creating a novel is a long game, so if you are really struggling, taking a few hours or a day of your writing schedule will not be a disaster; indeed, a chance to refresh and rethink should spark your imagination and allow you to see solutions hitherto hidden. Hit the library This is one of my main weapons of choice for breaking writer’s block! Researching your book on the internet is fine, but nothing beats an hour in the library. My advice: don’t look for anything specific, just let your mind wander and I guarantee you’ll find books of interest. Trust me, as you read, as you explore, new ideas and perspectives will emerge, which in turn can generate solutions. And I find just being in the library a relaxing experience, as though sitting among hundreds, thousands of other books brings home to me how much I really want to write, and that the effort (and pain!) of creation is worthwhile. In addition to the library, I also find that visiting art galleries and museums really sparks my imagination. I always discover new things, new ideas, and some of these inevitably end up influencing my book. When writing This Sacred Isle, trips to the British Museum, Tate Britain, Fitzwilliam Museum and many others gave me considerable inspiration to keep going, to keep creating, to keep making the story better and better. After visiting such places, I can’t wait to get writing as soon as I get home! Interrogate your story

Ask questions about your story, challenge elements you have long decided upon – characters, events, themes, imagery. What if a character says or does something different? Consider the impact if you turned your plot around – it doesn’t mean you have to change lots of things about your book, it will just provide some insights into the structure of your story and the characters within. In This Sacred Isle, the character of Lailoken was originally in the novel for much longer, but as developed further drafts of the book I struggled to see how he could contribute meaningfully to the story. On an early edit, I took some time to ask myself some key questions about his character – I realised that as well as being a mentor of sorts to Morcar, and a supplier of crucial exposition about the dragon Athanor, Lailoken represented a fearful reaction to the growing evil of Merlin, a reaction of hiding and isolation. Lailoken encourages Morcar to behave in the same manner, and it is Morcar’s determination to face evil, not to flee even when all seems hopeless, that drives the last act of the story. Drop the scene and move on If a scene is just too damned difficult to write, it probably means it's never going to work – at this point, rather than invest time and energy in fruitlessly making the scene work, I’d suggest you move on and devise another way to progress the plot. Don’t beat yourself up about it. Allow yourself to fail sometimes; expect to fail and learn from it. When I was writing The Map of the Known World, there was a I was pleased with, but when I read through the story it slowed the pace. I spent several days reworking the chapter, getting increasingly frustrated, nothing I did seemed to improve the situation. Eventually (out of near desperation!) I decided to try seeing how the story worked without the chapter – to my surprise, the sense of tension was enhanced. It was painful to make the cut (I had really enjoyed working on those particular scenes) but the book was better paced by removing the chapter and reshaping some plot points. Just write – anything! This is perhaps the most important cure of all. Just write something, anything and see where it goes. Don’t overthink, don’t seek perfection, don’t think long term. Write without the pressure of having to deliver something memorable – just write for the joy of writing. Of course, much of what you write will not appear in your final book, but you’ll unearth some nuggets and this will boost both your confidence and enjoyment. And finally, what not to do… Don’t just wait for inspiration to strike before writing. If you don't writing, inspiration will never strike, simple as that! All writers hit blocks, it’s inevitable and all part of the ongoing learning process. But you can push through and you’ll be a better writer when you do. How do you combat writer's block? Add a comment and join the conversation. |

Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed