|

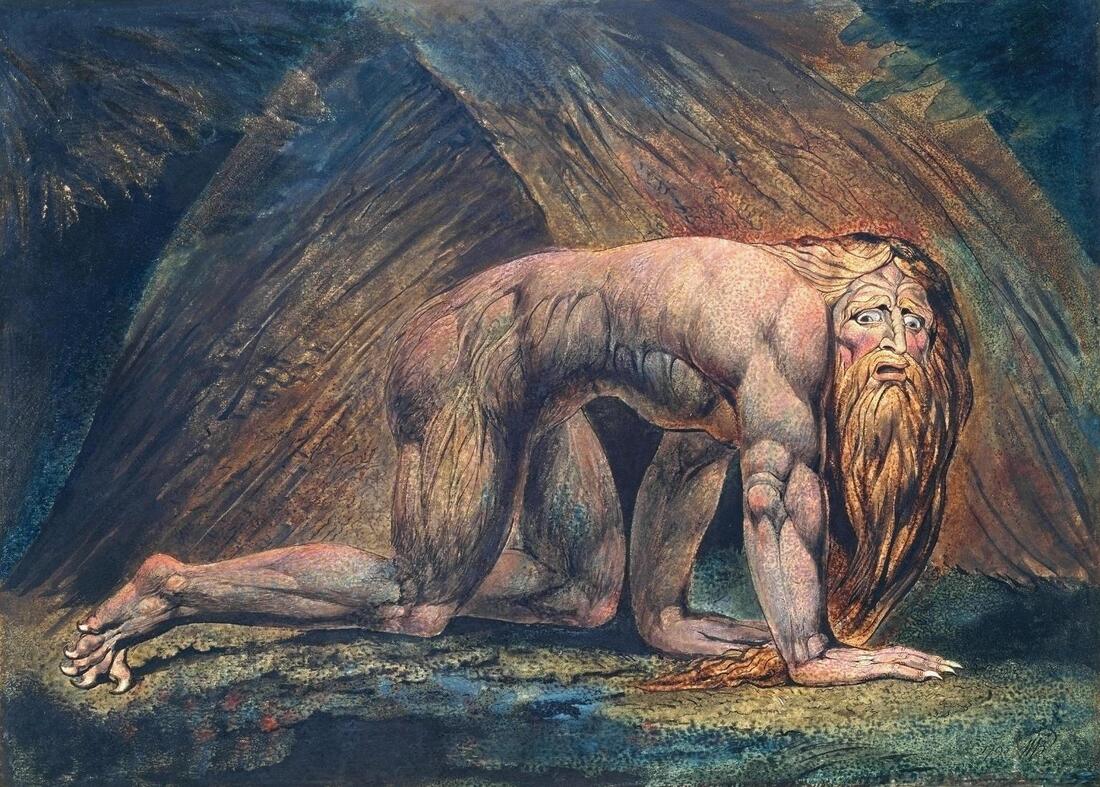

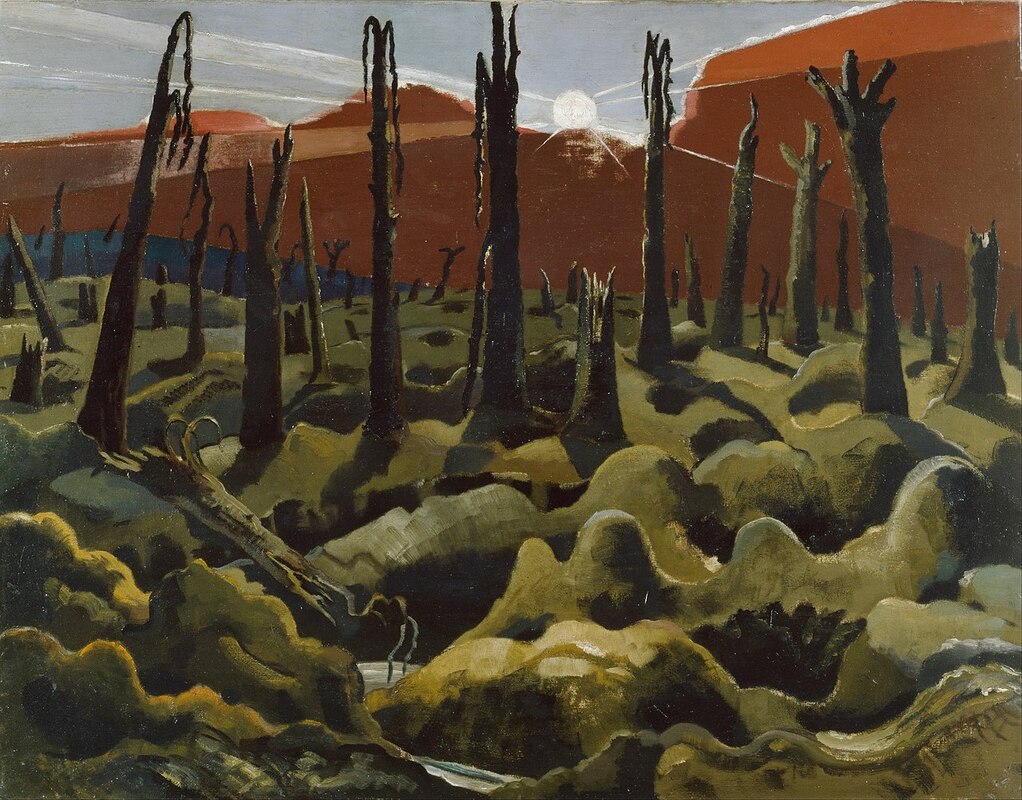

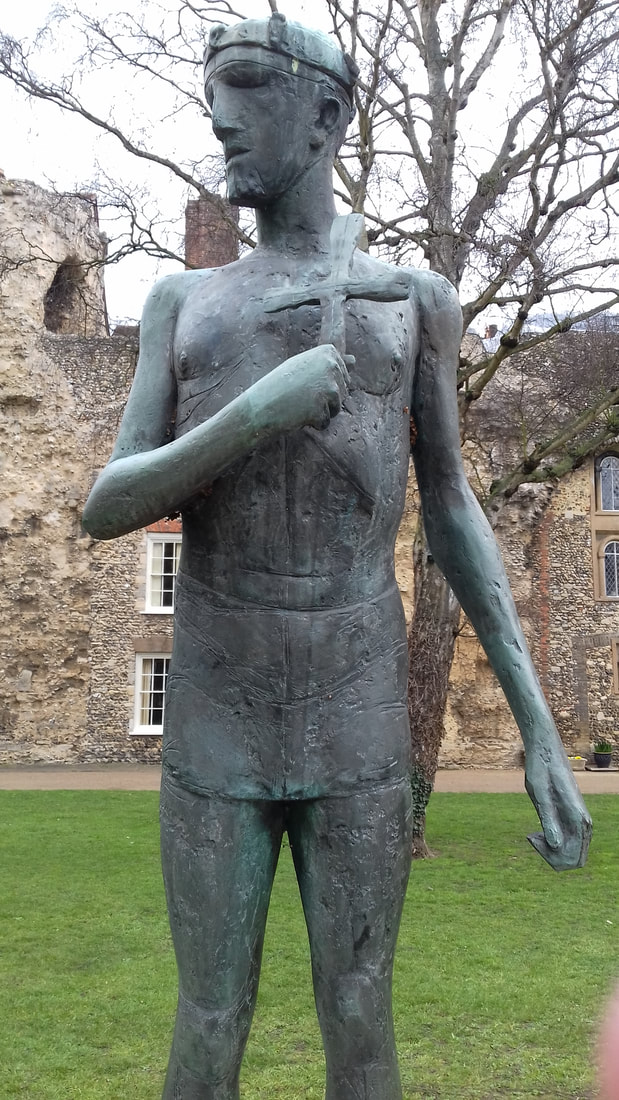

Like any author, I draw upon a broad range of inspirations when writing a book, and for me, visual art has always informed and influenced my writing. Although far from blessed in my drawing and painting skills, I’m rarely happier than when wandering around an art gallery! In this blog post, I am going to focus on four artists who have been particularly important and inspiring to me when I was working on my new novel The Waste. William Blake I have long been fascinated by the work of visionary painter and poet William Blake (1757-1827). His art is both highly personal and highly original, infused with his rebellious spirit and enormous imagination. Encompassing biblical and mythological themes, the delicate strangeness of Blake’s work is powerful and seeing the collection of his work is always a highlight of any visit to the Tate Britain. Through his art and prophetic books, Blake developed a very personal mythology with a host of symbolic characters, and this mythology, along with the graceful, idealised human figures in Blake’s art, was a significant influence for me when writing The Waste, especially when developing the characteristics of the alien Seraphim. The act of developing and writing a novel can be a hard slog, but to spend time researching and thinking about Blake’s art and writings was a pleasure in itself. Paul Nash If I have such a thing as a favourite artist, then I think it would be Paul Nash (1889-1946). Whether it’s the raw, uncompromising power of his First World War art, the melancholy of his Dymchurch paintings or the mythical energy of his work inspired by the Avebury stone circle, I find his work captivating, his symbols resonant and meaningful. Perhaps Nash’s best-known work is We Are Making A New World. I saw the original for the first time in an exhibition at the Imperial War Museum in London. Few paintings have had such an impact on me – the battle-ravaged, brutalised landscape reflected not only the hideous violence of war but Nash’s own emotional experience of the conflict. Consider the pallid sun peeking through the blood-red tide of clouds – is it striving to bring light and hope to the shattered world below, or is it too frightened to peer at the horror Mankind has inflicted? This painting makes an appearance in The Waste and Spare’s experience of viewing it certainly echoes my own. Through his paintings Paul Nash demonstrated an intense relationship with landscape, not just recording what his eyes saw, but adding deeply personal levels of symbolic meaning, giving the landscapes he portrayed an animated, vital presence. From his early drawings and paintings, influenced by Samuel Palmer and William Blake, to the harsh angles and blade-like waves of his Dymchurch work, which evoke such a sense of emptiness, of loss and depression, the landscapes of Nash are alive and mythic. This sense of place, the genius loci, as Nash referred to it when he described places such as Avebury, was something I wanted to reflect within my novel. The titular Waste of the book is both a literal and symbolic landscape, where the layers of human history are almost a tangible presence. I have no doubt Paul Nash will remain a primary inspiration for my writing. Dame Elisabeth Frink My first, very striking, encounter with the work of Dame Elisabeth Frink (1930-1993) took place in Bury St Edmunds in my home county of Suffolk. In the grounds of St Edmundsbury Cathedral stands a bronze statue of Edmund, a ninth century king of East Anglia. After being defeated in battle by the Great Viking army, it is said Edmund refused his enemies’ demand to renounce Christ and so was beaten, shot through with arrows and beheaded. Legend tells the Vikings threw Edmund’s severed head into the forest, but it was soon retrieved by those loyal to the king when they followed the cries of a mysterious wolf. Frink’s statue shows King Edmund as a young man, a cross grasped in his hand. This is not a caricature of a warrior or a king – there is pride in Edmund’s face but a sense of vulnerability, his slender body is fragile. Frink’s Edmund is very much a king, a saint, and a martyr, but still a human being. This often-unsettling combination of history, myth and human frailty seems to be present throughout much of Frink’s art. During the writing of The Waste, I was especially interested by Frink’s goggle head sculptures; shaped by Frink’s interest in themes of masculine aggression, the goggle heads’ sense of faceless authority very much shaped the look and attitude of the Shades, the cold, impersonal, unaccountable police force of my novel. The goggle head sculptures avoid eye contact, concealed behind polished headgear – they are dehumanised and as such offer a threat that cannot be reasoned with. The Shades in The Waste are human, but just as their visors hide their human faces, their humanity is also hidden and they appear almost machine-like, robotic. The unsettling and enigmatic nature of Elisabeth Frink's art continues to be both fascinating and inspiring. Alfred Wallis Alfred Wallis (1855 - 1942) produced profoundly personal art, painting images of ships, boats, Cornish villages and the sea. With no formal art training, Wallis only took up painting after his wife’s death – with little money for materials, he mostly painted on found pieces of cardboard. Wallis painted from memory, drawing on his sea-faring experiences, to capture a rapidly disappearing way of life. Wallis’s limited palette and distorted perspective give his work a distinctive look. Within his paintings, Wallis played with size and scale of objects, and although the paint is roughly applied, he often achieved high levels of detail. Wallis’s instinctive compositions give his paintings real vitality – you can almost taste the briny air, hear the waves booming. The art of Alfred Wallis, and discovering more about his life, unlocked for me the character of ‘The Captain’ in The Waste, who although is not meant to represent the real Wallis, does share many of the same motivations and obsessions. It is important not to romanticise the life of Alfred Wallis – he struggled with poverty and, it would appear, mental health difficulties – but he brought something profound and original into the world, and I hope he gained pleasure from the creation of his art.

The Waste is out now, available in eBook and paperback, and free to read through Kindle Unlimited.

0 Comments

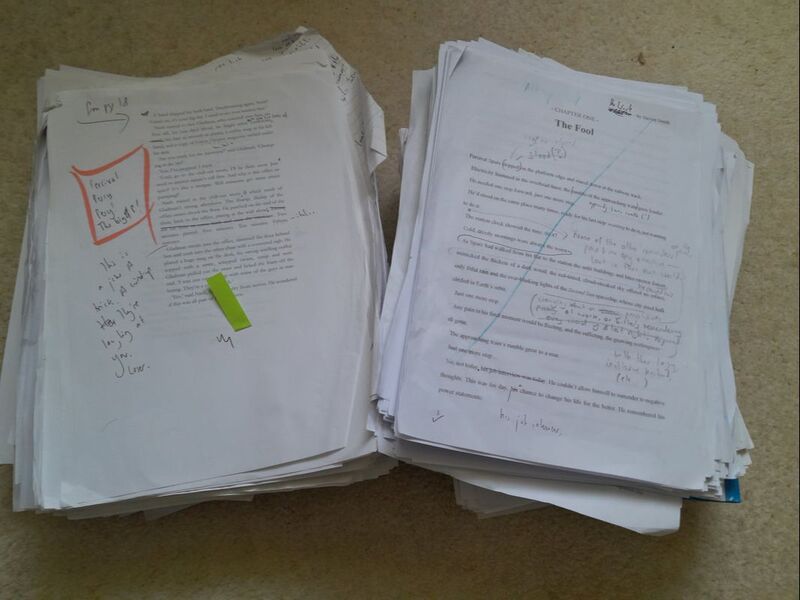

Although I wrote and published four novels before The Waste, my latest book dates back to my earliest attempts to start writing seriously. My first unfinished novel was a serious fiction story called Colony and was set in an alternate Earth occupied by an apparently benevolent alien race. Put simply, I didn’t have the skills or the experience to do the novel justice, so I abandoned the book and switched my efforts to writing for small press and indie SF / fantasy magazines for a couple of years before embarking on my first completed novel, the epic fantasy The Map of the Known World. And yet over the years, as a lover of science fiction and dystopian novels and films, the basic premise of Colony stayed with me. After completing my fourth novel, the historical fantasy This Sacred Isle, I returned to my SF story. The first thing that changed early in the writing was the title as Colony was the name of the (excellent) SF series starring Josh Holloway and Sarah Wayne Callies. My unfinished novel was also more of a police procedural but I moved away from that approach. However, one element that did remain was that of the aliens being, at least on the surface, benign, with their rule of Earth largely supported and unchallenged by humanity. Although my primary aim when writing any novel is to intrigue and entertain the reader, in The Waste I wanted to explore contemporary concerns and themes. So, for the setting of the book, I wanted a world with clear roots and parallels with our own. The Waste is set in an alternate version of modern Britain, for although this is a science fiction novel with aliens and spaceships, there is also homelessness, foodbanks, environmental damage, poor public housing, and the mistreatment of immigrants. For some, the new society created by the Seraphim is a paradise; for many others life remains a painful daily struggle. The world of The Waste is a dystopia, but a dystopia hiding in plain sight, where the quest for money, power and status is treasured above all else, where poverty is judged to be a symptom of personal weakness, where compassion for the suffering of others is seen as misguided, mawkish. In this world, all the functions of government, along with almost all commercial enterprises, are run by the vast, monolithic PAX company. The main character of The Waste is Percival Spare. By the metrics of his life – career, relationships, money – Spare believes he has utterly failed. He is lonely, unfulfilled and routine-trapped. In many ways, Spare’s journey as a character is not so much about taking risks – although that is certainly part of it – but about seeing, really seeing, the injustices of the world and realising he must do something, however small, however insignificant, to stand against these injustices. The Waste is a novel that went through many iterations, and although you can never be sure how a book will be received by readers, I was sure this was a book I wanted to write, felt compelled to write in some ways, and that provided ample motivation through the many years it took to reach the final version.

The Waste is published on 27 October - the eBook version is available for pre-order for just £0.99 / $0.99. The Stand has long been on my ‘to read’ list and I am glad to have finally read this epic thriller from Stephen King. The early stages of the novel are post-apocalyptic, as a manmade flu-like virus is accidently released from a top-secret US military laboratory, causing a catastrophic pandemic. Despite frantic, belated efforts by the government and the army to contain the outbreak, including brutal enforcement of martial law, 99% of humans die from the virus, and King vividly portrays the terror and despair as civilisation rapidly collapses – one scene that will stay with me is Larry Underwood’s nightmarish journey through the Lincoln Tunnel, a moment of visceral horror and tension. As the traumatised, often grief-stricken survivors try to regroup and make sense of their disintegrating world, The Stand moves towards more of a dark fantasy, and the shattered remnants of the United States gradually becomes the setting for an epic struggle between good and evil, and fear and paranoia become as deadly foes as the virus itself. For the survivors begin having strange dreams: either of a kindly, aged prophetess, Mother Abigail or of the ‘dark man’, Randall Flagg. Mother Abigail leads her followers to Boulder, Colorado, where they start to rebuild a society, facing challenges such as restoring the power, providing medical care (I felt sorry for Dick Ellis, the overworked veterinarian who is initially the only ‘doctor’ in the community) and shaping an effective government. Meanwhile, the demonic Randall Flagg beckons followers to his growing empire formed around Las Vegas, including murderer Lloyd Henreid (who Flagg rescues from prison and cannibalism…) and the pyromaniac Trashcan Man. And the stage is set for a struggle between the two communities, and the future of humanity… The Stand is a powerful, frequently disturbing novel, but at its core it is driven by insightful human details, which gives the book real emotional impact. One character I found especially interesting was Harold Lauder – he had been a social outcast at school and retains an obsessive love for Frannie Goldsmith, with whom he travelled to Boulder. (Minor spoiler alert) Despite becoming a valued and respected member of the community, Lauder cannot let go of the difficulties and rejections of his past, internal wounds that begin to lead him down a dark path. Harold Lauder is a complex character and is written with such skill by King, we can see how Lauder is twisted by a sense of betrayal, placing vengeance for past humiliations above embracing a new life for himself.

I also enjoyed the scene (again, minor spoiler alert) when Glen Bateman, a retired professor of sociology comes face-to-face with the demonic Randall Flagg – this moment is a powerful demonstration of how brittle authoritarian power can be when faced with mockery. Reading The Stand requires a significant time commitment from the reader, but in my experience, it was absolutely worth the effort. It is a gripping novel of huge power, encompassing fantasy, adventure, horror and much more, and from the first page you’re safely in the hands of a master storyteller. It is a long novel (and I read the extended / revised version) but for me the story never dragged and the scope of the novel justified the page-count. There is always a large number of characters in play, but the majority are so richly developed they are memorable as well as being key to propelling forward the plot. I have read (embarrassingly) little of Stephen King’s work before tackling The Stand, but I am definitely hooked now! I have just started reading The Dark Tower and look forward to losing myself in another epic dark fantasy… |

Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed