|

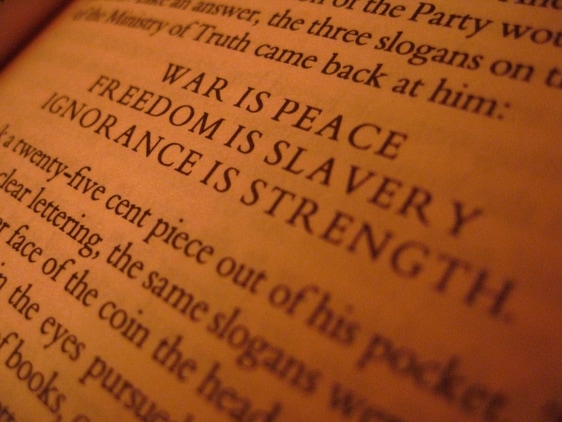

During the writing of This Sacred Isle, I realised it is in some ways a post-apocalyptic novel, as well as being an historical fantasy. The world of 6th century Britain existed within the bones of a fallen civilisation - Roman Britannia. This allowed me to explore within the book themes of identity and freedom, themes I will continue into my next novel, a dystopian SF novel called Second Sun. I have long been fascinated by dystopian novels and – with recent world events in mind - such books are very much in focus. I believe dystopian novels, certainly the best ones, hold a mirror up to our own world, allowing us to see dangers we can easily ignore; sometimes those dangers will be amplified within fictional words, but this only serves to make the warnings they possess more stark and pressing. Across two posts I am going to look at my favourite dystopian novels, and why they are important to me. This first post will look at three classic dystopian novels: We, Brave New World and 1984. We - Yevgeny Zamyatin We, by Russian novelist Yevgeny Zamyatin, in many ways set the template for the modern political dystopia. Set in the twenty-sixth century AD, We is narrated by D-503, a spacecraft engineer, who dwells in OneState, a city state where the programmed society is organised by strict logic and mathematical formulas. The story occurs long after the Two Hundred Years’ War – an enormously destructive conflict that wiped out the vast majority of humanity. OneState is surrounded by the Green Wall, which separates the citizens from the untamed nature beyond. The natural world is viewed with horror (OneState’s people eat food made from petroleum) and D-503 considers it ugly when compared to the manufactured environment in which he lives. In this world of glass buildings, there is little or no privacy (blinds only come down during the discreetly named Personal Hour) – it is a life lived on show, in public view. Peace and happiness are achieved at the price of a private life. Happiness comes through lives being controlled – freewill and choice are deemed dangerous and root causes of human misery. Indeed, at the start of the book D-503 is happy, he believes in the system. Opponents of OneState are even called ‘enemies of happiness’. I find OneState’s obsession with happiness a deeply resonant theme. In our society much emphasis is placed on the search for happiness, to the point where feeling unhappy (aside from conditions such as depression and anxiety) is almost seen as wrong, abnormal. But what, in our modern world, do we really mean when we talk of happiness – is it a feeling of deep contentment and satisfaction or does it mean empty pleasures offering an easy escape from reality and hardships? The citizens of OneState are lulled by comfort and ease – they choose not to see the tyranny around them or at least believe the oppression is worth the loss of freedom. This is an uncomfortable theme, for it is only through a sense of discontent, of wanting to change aspects of society that we challenge and overcome injustice. The citizens of OneState, who have numbers not names, are not individuals – just replaceable, forgettable cogs in the machine. With their lives ruled by ‘The Table’, human relationships and interactions are reduced to scheduled moments (such as the aforementioned Personal Hour) and spontaneity effectively outlawed. As a result, there is an entrenched absence of feelings – for example, consider the lack of pity, as D-503 recounts when some unfortunate colleagues are incinerated in a work accident: “I’m proud to note down here that this did not cause a second’s hitch in the rhythm of our work, no one flinched.” These cold, dispassionate words must be a warning to us, a warning that we must see our fellow human beings as individuals, with worth and rights, for if we do not, we risk further embedding misery and injustice within our own society. We is not an easy read and the tortured, turbulent mind of D-503 can be a confusing place – and I suspect there are levels of symbolic, philosophical and religious imagery and themes within the novel that would require multiple readings to begin to comprehend. But the book is worth the effort and We unquestionably laid key narrative and thematic foundations for many dystopian novels to follow. Brave New World - Aldous Huxley Brave New World is often heralded as one of the most influential and prophetical books of the twentieth century. Set in the far future, the World Controllers of the story have created a perfect world, using genetic science - every individual receives pre-natal / post-natal conditioning so as to accept his or her position in society, from the Alpha-Plus ruling class to the Epsilon-Minus Semi-Morons who are bred to perform menial tasks. This society is perfectly ordered, and control is strengthened through the habitual, state-endorsed, use of the drug soma, and other distractions such as ‘feelies’, a kind of proto Virtual Reality. In many senses, the people of the novel are controlled by pleasure and enjoyable distractions (a thematic link to We); when life is so good and so easy, why even think to challenge the status quo, what would be the purpose? This is not a tyranny of brutal physical oppression but a tyranny in which the citizens are imprisoned in a gilded-cage of amusement and ease. The World Controllers of Brave New World have perfected a society where the genetically bred humans have their basic needs of comfort, sex, food and pleasure met in abundance – in this state opposition, freethinking becomes irrelevant, or worse a danger to the blissful lives of the citizens. Bernard Marx is unhappy for he desires solitude and is disgusted by the endless pleasures of his society – he struggles to understand his discontent with the world, a feeling I think many of us would recognise. Bernard is a misfit – he is smaller than the other Alphas and his individualism places him in danger of exile. He does not meet the norms imposed by his society and thus is viewed with suspicion. When I first read Brave New World many years ago I was impressed by its brilliant invention and wit, but as time passes, I view the book with wonder at the continuing relevance of many of the concerns Huxley explored in his novel. Considering the rapid advances in technology in our own world, Brave New World simply becomes more relevant. It is increasingly possible to live a life in the virtual world, where you can in effect become another person, whoever you choose to be – submerged in such a pleasurable and stress-free life would you even care or notice that you are living in a dystopian world? Nineteen Eighty-Four - George Orwell When I first read Nineteen Eighty-Four I felt as though I had stepped inside a nightmare. Airstrip-One is a crucible of relentless pressure – I could scarcely comprehend the horror of the constant surveillance, the crushing conformity, the lingering danger of arrest and the sheer misery: horrible food, the bitter cold and the dilapidated living conditions. It is a wretched world, mutilated by an endless three-sided war – anger and sexual frustration are channelled into hatred towards enemies of the state real and imaginary. The most memorable display of this is the Two Minute Hate, where the Party Members are whipped into a frenzy of hatred.

“The horrible thing about the Two Minutes Hate was not that one was obliged to act a part, but that it was impossible to avoid joining in. Within thirty seconds any pretence was always unnecessary. A hideous ecstasy of fear and vindictiveness, a desire to kill, to torture, to smash faces in with a sledgehammer, seemed to flow through the whole group of people like an electric current, turning one even against one’s will into a grimacing, screaming lunatic.” So much of the language of Nineteen Eighty-Four has become part of our everyday idiom: Room 101, Big Brother, doublethink, thoughtcrime, Newspeak to use just a few examples. In some ways, such common use (often in trivial contexts) has diluted the power of these concepts; only when read as part of the actual book is their true power, and horror, revealed. For although this is a book with profound comments on politics and society, it is above all a book with a very human focus. We see Winston Smith’s suffering not just in existential terms, but in everyday terms: his blunt razors, the crumbling cigarettes, his coughing fits and varicose ulcers. Such a human perspective makes the horrors of Airstrip-One even more striking; we see how the oppression and privations take their toll on the citizens. We witness the misery and loneliness of an individual crushed and dehumanized by the tools of political terror. So what does Nineteen Eighty-Four say to us about our own world? While Big Brother style totalitarian states still exist, I would argue that the form of political control postulated by We and Brave New World – control through distraction – is closer to how Western society has developed. However, such methods are also evident in Nineteen Eighty-Four, especially in relation to the downtrodden proles, who are distracted from political involvement by mass entertainment, a dubious National Lottery and sport (and, where necessary, the iron fist of state security). The phenomenon of a constant bombardment of dubious ‘news’ is one we are increasingly familiar with and although we do not have telescreens watching our every move, we have CCTV monitors aplenty and the potent for tracking through phones and other devices. We may not be in Airstrip-One, but some of the parallels are a little uncomfortable. And it is difficult to read Winston Smith’s diary entry about his visit to the cinema, as he describes a film in which ships full of refugees are bombed in the Mediterranean – the audience laugh at the suffering of the refugees as they are bombed and drown. It seems horrific, unimaginable to be entertained by such images, but in affluent Western Europe do we not turn aside with indifference as refugees, children and adult alike, drown in the very same sea Orwell described, and show little compassion or concern, our emotions blunted by saturation on TV and the internet? Others may disagree – and they have the right to do so – but for me this is just one example where Orwell shows us the callousness of which people, all people, are capable, and we would be wise to take heed and consider our own responses. I cannot overstate the importance Nineteen Eighty-Four has for me. Reading it first as a teenager, it changed how I thought about books, society and politics. Even now, the book still burns with fury and although it cannot accurately be called a prophecy, Orwell’s book is a warning, one I believe will endure through the ages. In conclusion, all these books rally against orthodoxy and comfortable, unquestioning conformity. They challenge us – they hold up a mirror and when we look, if we choose to look, we see our worst side staring back. These books say we have to think better, we have to act better to avoid slipping into the nightmares they so chillingly describe. In the next post, I will look at two more, very different, dystopian books. Which dystopian books do you find most powerful? Add a comment and join the conversation.

1 Comment

|

Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed