|

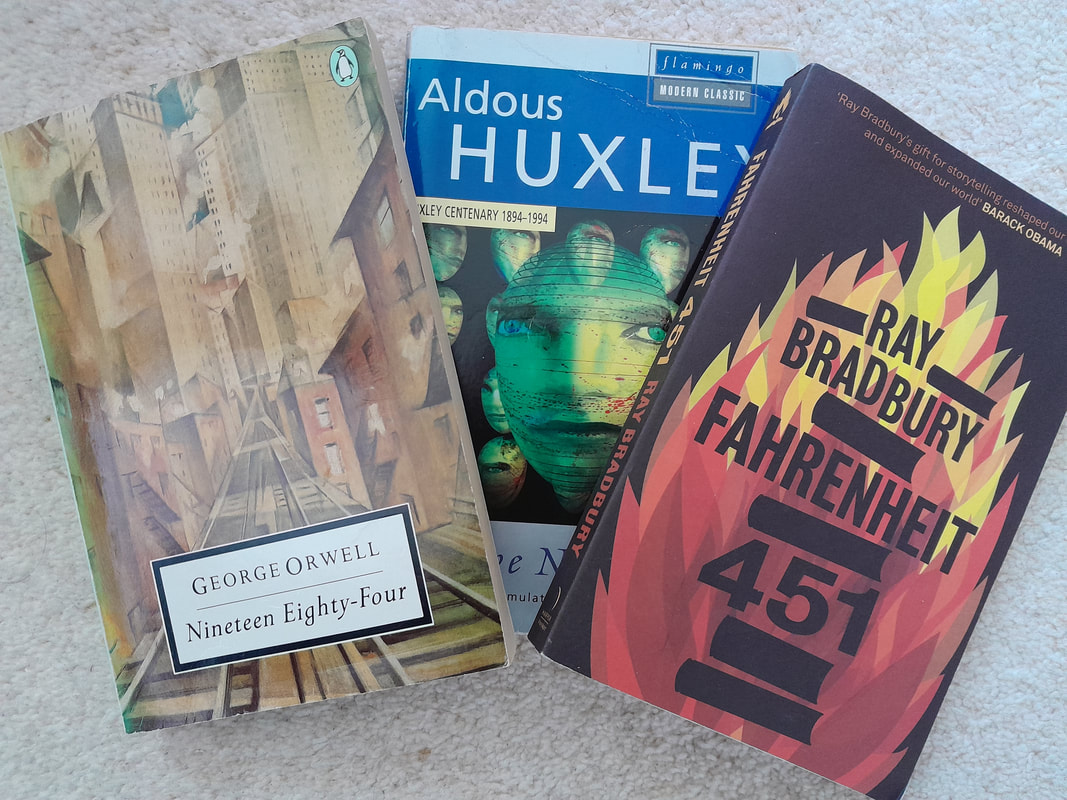

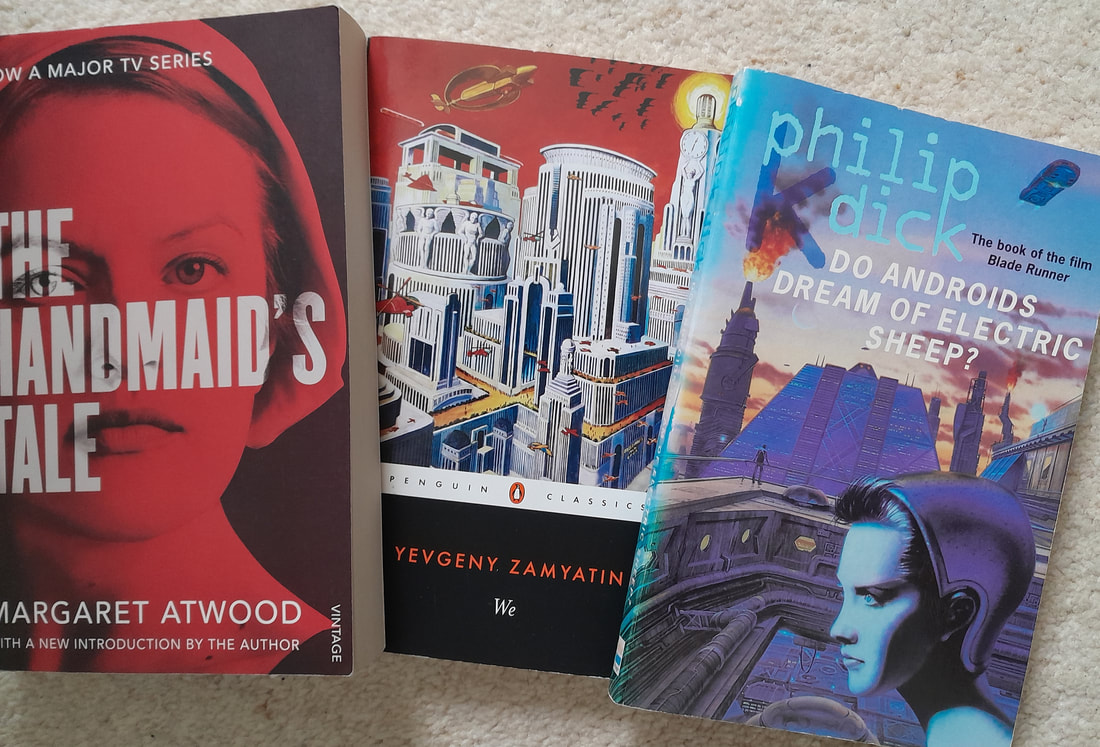

Dystopian science fiction is a genre I've long enjoyed and when I came to write The Waste, there were several novels that influenced and inspired me. Brave New World by Aldous Huxley Brave New World is often cited as one of the most influential and prophetical books of the twentieth century. Set in the far future, the World Controllers of the story have strived to create a perfect world. Every individual receives pre-natal / post-natal conditioning so as to accept his or her position in society, from the Alpha-Plus ruling class to the Epsilon-Minus Semi-Morons who are bred to perform menial tasks. This society is perfectly ordered, and this control is strengthened through the state-endorsed use of the drug soma, and other pleasurable distractions. In many senses, the people of the novel are controlled by their pleasure and distractions; when life is so good and so easy, why even think to challenge the status quo, what would be the purpose? This is not a tyranny of brutal physical oppression, enforced by military strength and prison camps, but a tyranny in which the citizens are imprisoned in a gilded-cage of amusement and ease. I found this a fascinating concept: that a dystopian could be so insidious, almost hiding in plain sight with a benevolent façade. Some of the thematic elements of Brave New World certainly influenced parts of The Waste. In the society shaped by the alien Seraphim, people are encouraged to focus only on their own needs and pleasures, with any concerns for wider society deemed odd, even suspicious – like the genetically bred humans of Brave New World, do they even notice they are living in a dystopian world, or if they did, would they care? The titular Waste of my novel, a vast open-air prison, was also in part influenced by the Savage Reservation visited by Bernard Marx and Lenina Crowne in Brave New World. Brave New World still impresses with its brilliant invention and wit, and as time passes, I’d argue Huxley’s novel simply becomes more and more relevant, and perhaps more and more troubling. Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell To the best of my memory, Nineteen Eighty-Four was the first dystopian novel I read and it is a book that certainly leaves a deep impression and although I have re-read it several times, its impact is never lessened. Airstrip-One feels like a nightmare, a crucible of relentless pressure: the constant surveillance, the crushing conformity, the lingering danger of arrest and the sheer misery of the horrible food, the bitter cold and the dilapidated living conditions. And in this wretched world, mutilated by an endless three-sided war, anger and sexual frustration are channeled into hatred towards enemies of the state real and imaginary. The most memorable display of this is the Two Minute Hate, where the Party Members are whipped into a frenzy of loathing. Outside of the Party members, the rest of the population of Airstrip-One, known as the proles, are distracted from political involvement by mass entertainment, a dubious National Lottery and sport (and, where necessary, the iron fist of state security). And it is difficult to read Winston Smith’s diary entry about his visit to the cinema, as he describes a film in which ships full of refugees are bombed in the Mediterranean, and not consider our own society’s indifference, even hostility, as children and adult alike drown in the very same sea Orwell described. In The Waste, this influenced the character of Oswald Beckett who shows no sympathy to the desperate refugees for whom he is responsible, seeing them not as people but as data to be controlled as part of reaching budgetary targets and developing his blossoming career. Nineteen Eighty-Four is undoubtedly a book with profound comments on politics and society, it remains a story with a very human focus. We see Winston Smith’s suffering in everyday terms: the constant bombardment of propaganda, his blunt razors, the crumbling cigarettes, his coughing fits and varicose ulcers. The readers sees the misery and loneliness of an individual crushed and dehumanized by the tools of political terror. This approach influenced me when I wrote The Waste, and rather than take a broad view, I wanted to explore the society created by the alien Seraphim mainly through the lens of one ordinary person. Nineteen Eighty-Four has had a huge influence on me as a reader and a writer. Orwell’s novel continues to burn with fury is a warning to us all, a warning I believe will endure through the ages. Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury In the future society of Fahrenheit 451 all books are illegal and if any are discovered, they are burned, for books are considered disruptive, dangerous, a cause of unhappiness. Guy Montag is a ‘fireman’, whose job is to find books and destroy them. Within this world, books are no longer valued and instead people have moved to new and addictive forms of media, encapsulated by the ‘parlour walls’, screens that fill entire walls and interact with the viewers. This media is seen as a better fit for an increasingly rapid pace of life and shortened attention spans. Initially settled in his job and home life, Montag’s unease with this society grows as he feels increasingly uncomfortable with the mind-numbing ‘entertainment’, which addicts so many people, and he begins to doubt the wisdom of book burning, especially when he sees the lengths some custodians are willing to go to protect their books. Soon, Montag begins hiding books himself and the experience of reading starts to change him… These ideas certainly influenced parts of The Waste. For example, although in my novel, books are not banned as such, they are considered quaint, redundant even – they have simply been supplanted by easier, less demanding media. The alien Seraphim encourage humans to only consider the present, to ignore or forget the pain of the past; books, as stores of knowledge, ideas and experiences, play no part in this world view. Museums and art galleries likewise are considered irrelevant and so close down out of apathy rather than a direct decree – of course, the Seraphim are not above appropriating works of human art when so inclined and hoard their treasures out of public view. Other books: Although these three books influenced my writing of The Waste, there are several other dystopian novels that were significant touchstones too, such as The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood, We by Yevgeny Zamyatin and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick, and I would definitely recommend these all as powerful, thought-provoking reads.

The Waste is out now, available in eBook and paperback, and free to read through Kindle Unlimited.

5 Comments

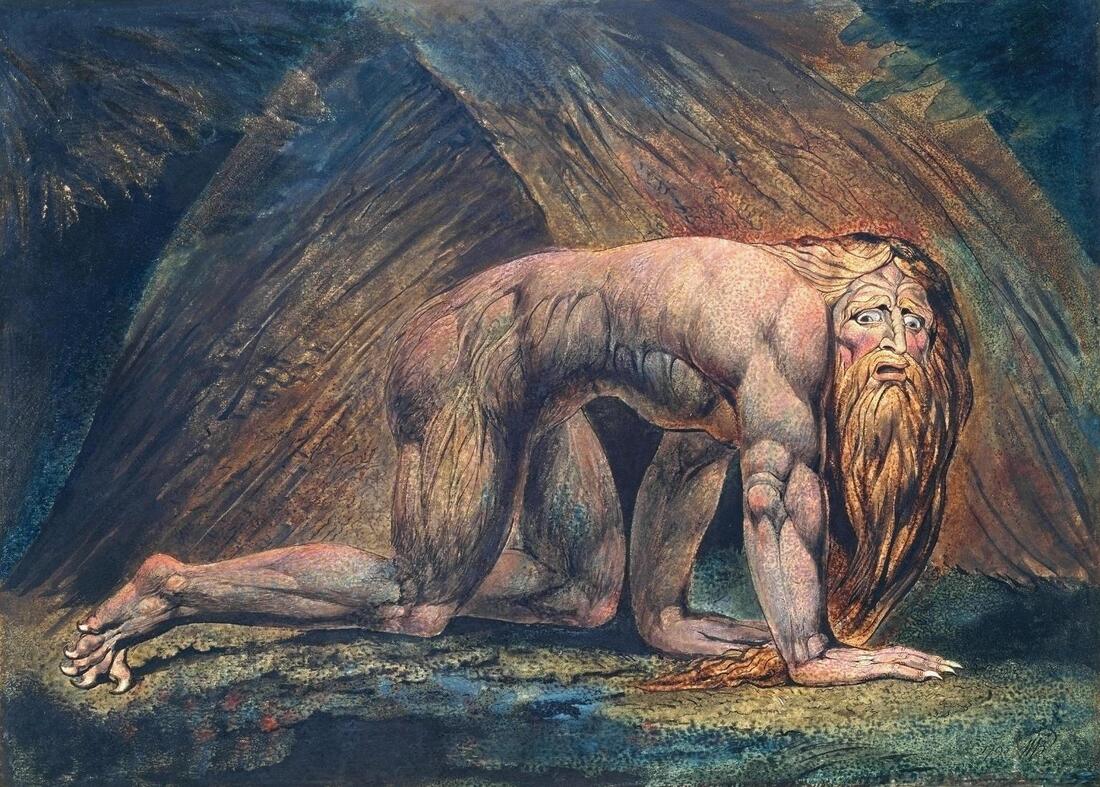

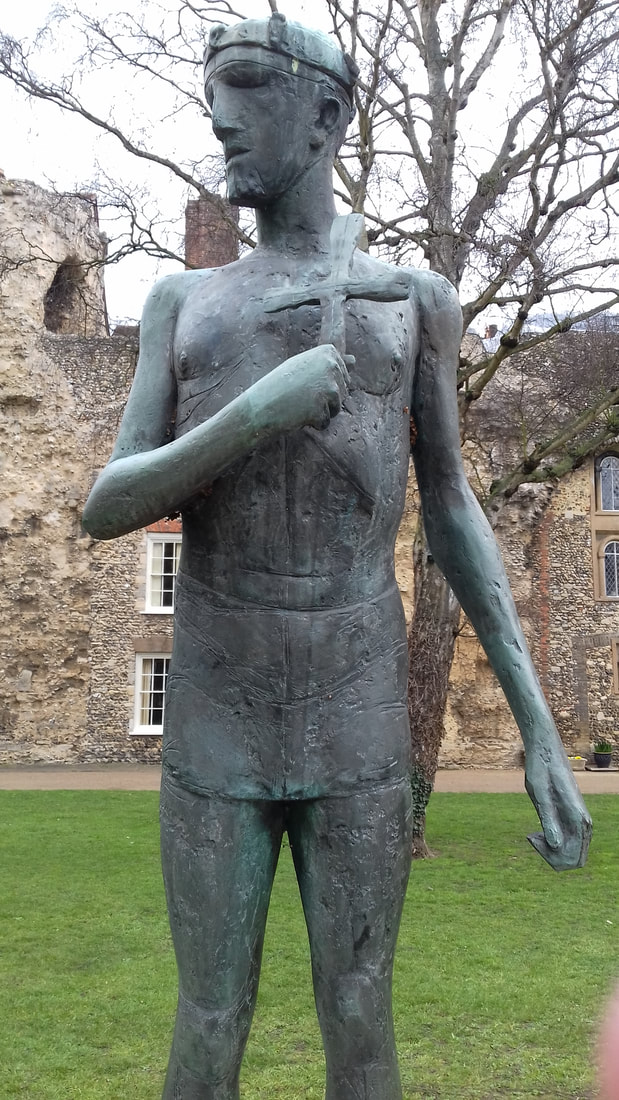

Like any author, I draw upon a broad range of inspirations when writing a book, and for me, visual art has always informed and influenced my writing. Although far from blessed in my drawing and painting skills, I’m rarely happier than when wandering around an art gallery! In this blog post, I am going to focus on four artists who have been particularly important and inspiring to me when I was working on my new novel The Waste. William Blake I have long been fascinated by the work of visionary painter and poet William Blake (1757-1827). His art is both highly personal and highly original, infused with his rebellious spirit and enormous imagination. Encompassing biblical and mythological themes, the delicate strangeness of Blake’s work is powerful and seeing the collection of his work is always a highlight of any visit to the Tate Britain. Through his art and prophetic books, Blake developed a very personal mythology with a host of symbolic characters, and this mythology, along with the graceful, idealised human figures in Blake’s art, was a significant influence for me when writing The Waste, especially when developing the characteristics of the alien Seraphim. The act of developing and writing a novel can be a hard slog, but to spend time researching and thinking about Blake’s art and writings was a pleasure in itself. Paul Nash If I have such a thing as a favourite artist, then I think it would be Paul Nash (1889-1946). Whether it’s the raw, uncompromising power of his First World War art, the melancholy of his Dymchurch paintings or the mythical energy of his work inspired by the Avebury stone circle, I find his work captivating, his symbols resonant and meaningful. Perhaps Nash’s best-known work is We Are Making A New World. I saw the original for the first time in an exhibition at the Imperial War Museum in London. Few paintings have had such an impact on me – the battle-ravaged, brutalised landscape reflected not only the hideous violence of war but Nash’s own emotional experience of the conflict. Consider the pallid sun peeking through the blood-red tide of clouds – is it striving to bring light and hope to the shattered world below, or is it too frightened to peer at the horror Mankind has inflicted? This painting makes an appearance in The Waste and Spare’s experience of viewing it certainly echoes my own. Through his paintings Paul Nash demonstrated an intense relationship with landscape, not just recording what his eyes saw, but adding deeply personal levels of symbolic meaning, giving the landscapes he portrayed an animated, vital presence. From his early drawings and paintings, influenced by Samuel Palmer and William Blake, to the harsh angles and blade-like waves of his Dymchurch work, which evoke such a sense of emptiness, of loss and depression, the landscapes of Nash are alive and mythic. This sense of place, the genius loci, as Nash referred to it when he described places such as Avebury, was something I wanted to reflect within my novel. The titular Waste of the book is both a literal and symbolic landscape, where the layers of human history are almost a tangible presence. I have no doubt Paul Nash will remain a primary inspiration for my writing. Dame Elisabeth Frink My first, very striking, encounter with the work of Dame Elisabeth Frink (1930-1993) took place in Bury St Edmunds in my home county of Suffolk. In the grounds of St Edmundsbury Cathedral stands a bronze statue of Edmund, a ninth century king of East Anglia. After being defeated in battle by the Great Viking army, it is said Edmund refused his enemies’ demand to renounce Christ and so was beaten, shot through with arrows and beheaded. Legend tells the Vikings threw Edmund’s severed head into the forest, but it was soon retrieved by those loyal to the king when they followed the cries of a mysterious wolf. Frink’s statue shows King Edmund as a young man, a cross grasped in his hand. This is not a caricature of a warrior or a king – there is pride in Edmund’s face but a sense of vulnerability, his slender body is fragile. Frink’s Edmund is very much a king, a saint, and a martyr, but still a human being. This often-unsettling combination of history, myth and human frailty seems to be present throughout much of Frink’s art. During the writing of The Waste, I was especially interested by Frink’s goggle head sculptures; shaped by Frink’s interest in themes of masculine aggression, the goggle heads’ sense of faceless authority very much shaped the look and attitude of the Shades, the cold, impersonal, unaccountable police force of my novel. The goggle head sculptures avoid eye contact, concealed behind polished headgear – they are dehumanised and as such offer a threat that cannot be reasoned with. The Shades in The Waste are human, but just as their visors hide their human faces, their humanity is also hidden and they appear almost machine-like, robotic. The unsettling and enigmatic nature of Elisabeth Frink's art continues to be both fascinating and inspiring. Alfred Wallis Alfred Wallis (1855 - 1942) produced profoundly personal art, painting images of ships, boats, Cornish villages and the sea. With no formal art training, Wallis only took up painting after his wife’s death – with little money for materials, he mostly painted on found pieces of cardboard. Wallis painted from memory, drawing on his sea-faring experiences, to capture a rapidly disappearing way of life. Wallis’s limited palette and distorted perspective give his work a distinctive look. Within his paintings, Wallis played with size and scale of objects, and although the paint is roughly applied, he often achieved high levels of detail. Wallis’s instinctive compositions give his paintings real vitality – you can almost taste the briny air, hear the waves booming. The art of Alfred Wallis, and discovering more about his life, unlocked for me the character of ‘The Captain’ in The Waste, who although is not meant to represent the real Wallis, does share many of the same motivations and obsessions. It is important not to romanticise the life of Alfred Wallis – he struggled with poverty and, it would appear, mental health difficulties – but he brought something profound and original into the world, and I hope he gained pleasure from the creation of his art.

The Waste is out now, available in eBook and paperback, and free to read through Kindle Unlimited. Landscape, and a sense of place, has always been important in my writing and my new science fiction dystopian novel The Waste is no exception. The novel moves through London, Gippeswic (an alternate version of Ipswich in Suffolk) to the Waste, which is a massive open-air prison covering a large swathe of south-western England. In this blog post, I will cover some of the real-world locations that helped inspire my novel. London Parts of the novel take place in (a much changed) City of London, with buildings such as the Shard, Saint Paul’s Cathedral, Saint Mary Woolnoth church and Liverpool Street Station appearing in thinly veiled forms. This is an area of London steeped in history, which I always find fascinating and enjoy walking around (especially when quieter at the weekends) and it formed an interesting backdrop to parts of the story. Within the novel, these flashes of history also contrast with the society the Seraphim are encouraging humans to build: a society focused only on the present, only on personal gain and pleasure. The inclusion of Saint Mary Woolnoth church is also a nod to The Wasteland by TS Eliot, which inspired some of the imagery in the novel. Avebury World Heritage site The area around Avebury in Wiltshire contains an extraordinary cluster of monuments dating to the Neolithic and Bronze Age, including the famous Avebury Stone circle, Silbury Hill and West Kennet Long Barrow. Having been fortunate enough to visit this area on a few occasions, it is difficult to put into words the atmosphere this landscape exudes. As you walk around the henge and stone circle at Avebury, or face the imposing mass of Silbury Hill, or walk up to the mysterious West Kennet Long Barrow, there is a sense of deep time, of landscape shaped by countless layers of human history. From the earliest stages of writing The Waste, Avebury and the surrounding area always formed a key location in the story. In the book, the henge and stone circle at Avebury appears as Havock, the chief settlement of the dreaded Mohock clan, while Silbury Hill emerges in grisly fashion as their chosen place for executions. West Kennet Long Barrow also has a fleeting but important appearance. One of the reasons Avebury interested me in the first place was the work of artist Paul Nash, who has long been one of my favourite artists. Nash had a profound sense of landscape, with a powerful emotional attachment to certain places such as Avebury and Dymchurch, places which possessed a quality he referred to as the genius loci. Although the Waste is a prison, and a dangerous and savage place, it is also less touched and polluted by the modern world – as well as being at times horrifying, I wanted the Waste to be a dreamlike landscape, rich with a sense of history and symbolism. I believe this quote from Paul Nash encapsulates the sense of what I was reaching for:

"The divisions we may hold between night and day - waking world and that of dream, reality and the other thing, do not hold. They are penetrable, they are porous, translucent, transparent; in a word they are not there." 'Dreams', undated typescript, Tate Archive The settings in The Waste are key elements in the novel, both challenging and revealing the characters, and although this is science fiction, they help achieve a sense of reality and history. The Waste is out now, available in eBook and paperback, and free to read through Kindle Unlimited. Image of St Paul's Cathedral by Raygee78 from Pixabay Although I wrote and published four novels before The Waste, my latest book dates back to my earliest attempts to start writing seriously. My first unfinished novel was a serious fiction story called Colony and was set in an alternate Earth occupied by an apparently benevolent alien race. Put simply, I didn’t have the skills or the experience to do the novel justice, so I abandoned the book and switched my efforts to writing for small press and indie SF / fantasy magazines for a couple of years before embarking on my first completed novel, the epic fantasy The Map of the Known World. And yet over the years, as a lover of science fiction and dystopian novels and films, the basic premise of Colony stayed with me. After completing my fourth novel, the historical fantasy This Sacred Isle, I returned to my SF story. The first thing that changed early in the writing was the title as Colony was the name of the (excellent) SF series starring Josh Holloway and Sarah Wayne Callies. My unfinished novel was also more of a police procedural but I moved away from that approach. However, one element that did remain was that of the aliens being, at least on the surface, benign, with their rule of Earth largely supported and unchallenged by humanity. Although my primary aim when writing any novel is to intrigue and entertain the reader, in The Waste I wanted to explore contemporary concerns and themes. So, for the setting of the book, I wanted a world with clear roots and parallels with our own. The Waste is set in an alternate version of modern Britain, for although this is a science fiction novel with aliens and spaceships, there is also homelessness, foodbanks, environmental damage, poor public housing, and the mistreatment of immigrants. For some, the new society created by the Seraphim is a paradise; for many others life remains a painful daily struggle. The world of The Waste is a dystopia, but a dystopia hiding in plain sight, where the quest for money, power and status is treasured above all else, where poverty is judged to be a symptom of personal weakness, where compassion for the suffering of others is seen as misguided, mawkish. In this world, all the functions of government, along with almost all commercial enterprises, are run by the vast, monolithic PAX company. The main character of The Waste is Percival Spare. By the metrics of his life – career, relationships, money – Spare believes he has utterly failed. He is lonely, unfulfilled and routine-trapped. In many ways, Spare’s journey as a character is not so much about taking risks – although that is certainly part of it – but about seeing, really seeing, the injustices of the world and realising he must do something, however small, however insignificant, to stand against these injustices. The Waste is a novel that went through many iterations, and although you can never be sure how a book will be received by readers, I was sure this was a book I wanted to write, felt compelled to write in some ways, and that provided ample motivation through the many years it took to reach the final version.

The Waste is published on 27 October - the eBook version is available for pre-order for just £0.99 / $0.99. My new novel The Waste is being published on Friday 27th October and the eBook version is now available on pre-order for the special price of just £0.99 / $0.99 until 4th November. The Waste is a dystopian science fiction thriller exploring themes of power and injustice. For three decades Earth has been ruled by the alien Seraphim - led by the immortal, godlike Urizen, the Seraphim urge humans to strive for lives of wealth and pleasure, unshackled from politics and religion.

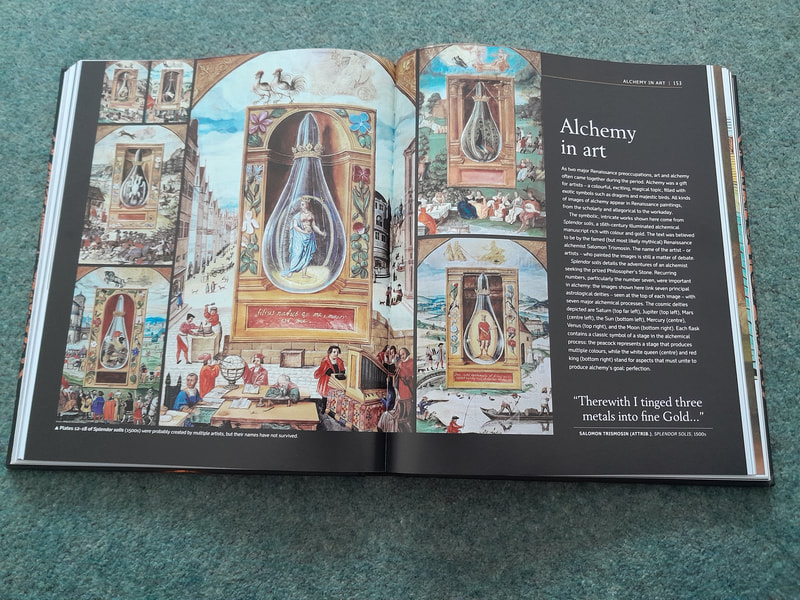

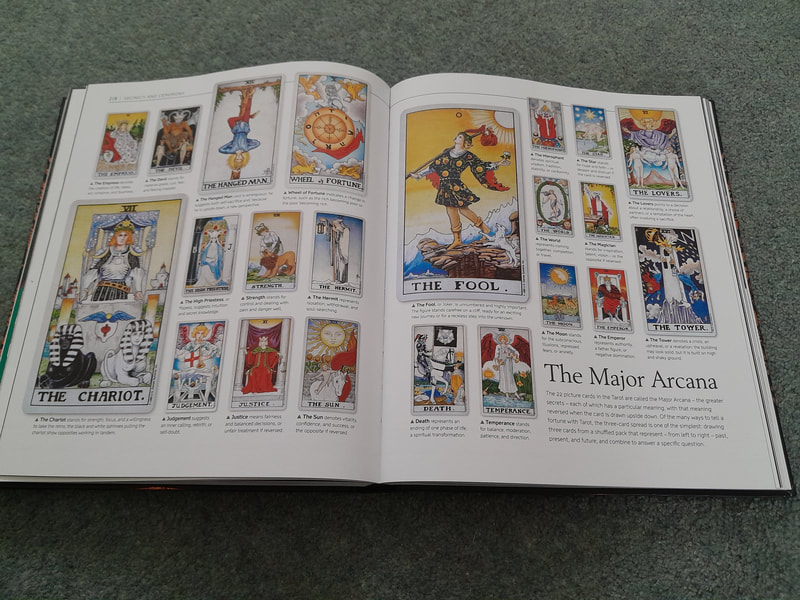

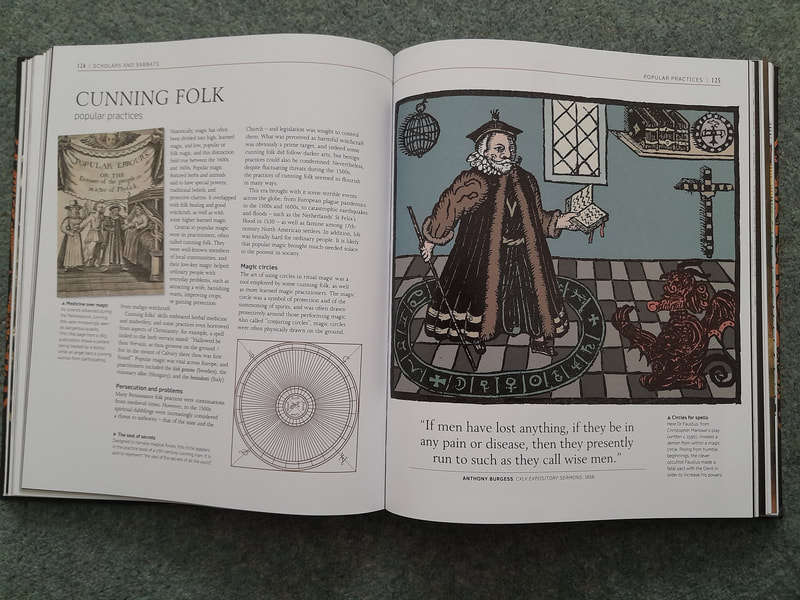

Meanwhile, lonely office worker Percival Spare is not used to excitement or danger, but an encounter with a mysterious stranger hurls him into a web of intrigue. Now he must venture into the Waste, a vast prison where the inmates are condemned to remain until they die. For within those lawless lands, Spare must uncover a shattering secret about the Seraphim, a secret that could even save humanity, or destroy it... The Waste would appeal to readers who enjoy dystopian novels such as Nineteen Eighty-Four, Brave New World and Fahrenheit 451. Get your eBook today for the special pre-order / first week price of just £0.99 / $0.99! And remember: we have never been alone... Professor Suzannah Lipscomb’s excellent foreword to A History of Magic, Witchcraft & the Occult sets the tone for this fascinating book, which explores how humans have sought to understand the universe and their place within it, and how they can appease or control spiritual forces to influence their environment. As seems to be standard with DK titles, the book is beautifully designed, with lavish illustrations (including paintings, photographs and woodcuts) and quick-fact panels to define and explain key information. The book is an intriguing journey through magical history, travelling from prehistoric times to the modern world, encompassing divination, alchemy, shamanism, Wicca and so much more. The broad historical narrative unfolds chronologically and takes a global view, drawing on cultures, beliefs and practices from across the world. There are many highlights I could mention, but I found the chapters on Mesopotamian magic (I’d also recommend The First Ghosts by Irving Finkel on this topic) and Renaissance folk magic especially engrossing. I bought the book as part of research for my latest novel, and while it has certainly proved useful in that regard, it is also a pleasure to read and there is always something unexpected to find. The sheer scope of the book inevitably means the subjects are not explored in great depth, but there is enough detail to interest the reader and to encourage further and research.

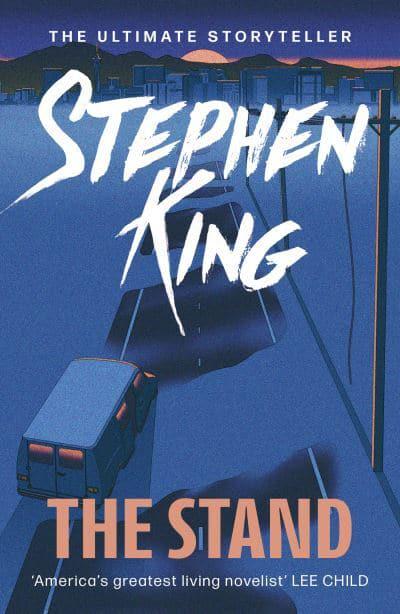

A History of Magic, Witchcraft & the Occult gives the reader a good sense of the important role magical practices and beliefs have played in shaping civilisations around the world, and the ways in which they continue to enrich many people’s lives. So, whether you’re looking to discover more about the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, Mayan cosmic cycles, tarot or countless other magical subjects, you’ll find something in this book to spark your imagination or inspire your creativity. If you’re interested in learning more about the history of magic, I would also recommend The History of Magic by Chris Gosden (which gives a more in-depth survey of the subject, and which I reviewed in a previous blog post), and from a British perspective, Pagan Britain by Professor Ronald Hutton and The Book of English Magic by Philip Carr-Gomm and Richard Heygate. The Stand has long been on my ‘to read’ list and I am glad to have finally read this epic thriller from Stephen King. The early stages of the novel are post-apocalyptic, as a manmade flu-like virus is accidently released from a top-secret US military laboratory, causing a catastrophic pandemic. Despite frantic, belated efforts by the government and the army to contain the outbreak, including brutal enforcement of martial law, 99% of humans die from the virus, and King vividly portrays the terror and despair as civilisation rapidly collapses – one scene that will stay with me is Larry Underwood’s nightmarish journey through the Lincoln Tunnel, a moment of visceral horror and tension. As the traumatised, often grief-stricken survivors try to regroup and make sense of their disintegrating world, The Stand moves towards more of a dark fantasy, and the shattered remnants of the United States gradually becomes the setting for an epic struggle between good and evil, and fear and paranoia become as deadly foes as the virus itself. For the survivors begin having strange dreams: either of a kindly, aged prophetess, Mother Abigail or of the ‘dark man’, Randall Flagg. Mother Abigail leads her followers to Boulder, Colorado, where they start to rebuild a society, facing challenges such as restoring the power, providing medical care (I felt sorry for Dick Ellis, the overworked veterinarian who is initially the only ‘doctor’ in the community) and shaping an effective government. Meanwhile, the demonic Randall Flagg beckons followers to his growing empire formed around Las Vegas, including murderer Lloyd Henreid (who Flagg rescues from prison and cannibalism…) and the pyromaniac Trashcan Man. And the stage is set for a struggle between the two communities, and the future of humanity… The Stand is a powerful, frequently disturbing novel, but at its core it is driven by insightful human details, which gives the book real emotional impact. One character I found especially interesting was Harold Lauder – he had been a social outcast at school and retains an obsessive love for Frannie Goldsmith, with whom he travelled to Boulder. (Minor spoiler alert) Despite becoming a valued and respected member of the community, Lauder cannot let go of the difficulties and rejections of his past, internal wounds that begin to lead him down a dark path. Harold Lauder is a complex character and is written with such skill by King, we can see how Lauder is twisted by a sense of betrayal, placing vengeance for past humiliations above embracing a new life for himself.

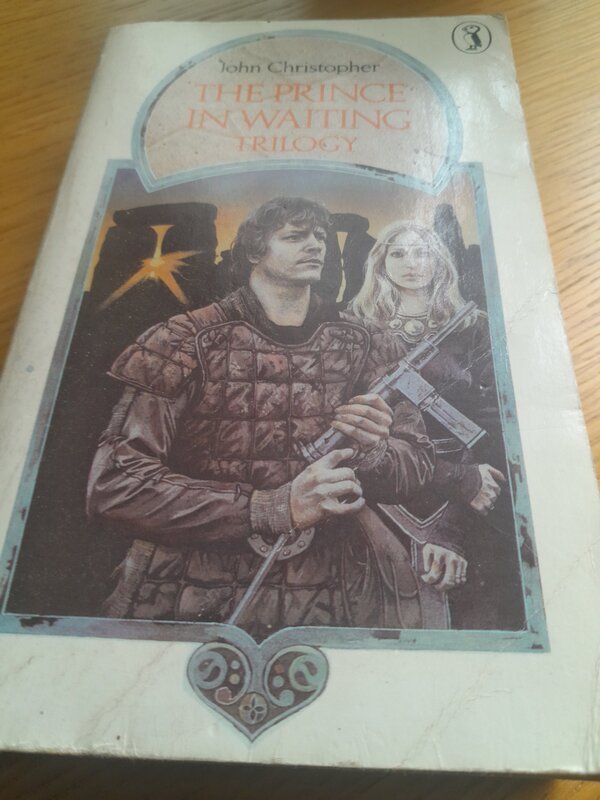

I also enjoyed the scene (again, minor spoiler alert) when Glen Bateman, a retired professor of sociology comes face-to-face with the demonic Randall Flagg – this moment is a powerful demonstration of how brittle authoritarian power can be when faced with mockery. Reading The Stand requires a significant time commitment from the reader, but in my experience, it was absolutely worth the effort. It is a gripping novel of huge power, encompassing fantasy, adventure, horror and much more, and from the first page you’re safely in the hands of a master storyteller. It is a long novel (and I read the extended / revised version) but for me the story never dragged and the scope of the novel justified the page-count. There is always a large number of characters in play, but the majority are so richly developed they are memorable as well as being key to propelling forward the plot. I have read (embarrassingly) little of Stephen King’s work before tackling The Stand, but I am definitely hooked now! I have just started reading The Dark Tower and look forward to losing myself in another epic dark fantasy… The Prince in Waiting trilogy (aka Sword of the Spirits) is an epic post-apocalyptic fantasy series from John Christopher, the author of books such as The Tripods and The Death of Grass. In a future Britain shattered by the Disaster (the true nature of which is revealed during the story), society has reverted to a medieval form, with the machines of the past rejected and reviled as the causes of the Disaster – anyone unwise enough to meddle with ‘ancient’ technology is put to death. All spiritual matters are dictated by the monastic-like Seers, whose role it is to interpret the will of the ‘Spirits’; Christians exist but as a marginal, often hated minority. Following the Disaster, birth defects are more common, leading to strict castes in society, with ‘true men’. ‘dwarfs’, who are permitted to work as blacksmiths to forge weapons, and the lowest social group, ‘polymufs’, who are denied many freedoms and are assigned the most menial tasks and treated as slaves. The protagonist of the books (I hesitate to say hero) is Luke, who lives in the walled city of Winchester, a powerful, militaristic realm, which regularly goes to war with neighbouring settlements. Luke becomes the Prince in Waiting, heir to the ruler of Winchester, but more than this, the Seers have planned he will be the one to unite the warring cities.

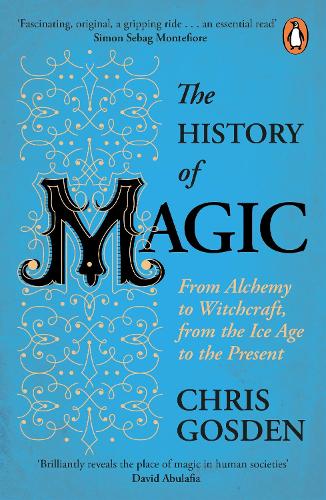

But Luke is a flawed choice – for all his undoubted bravery and fighting skills, he is ambitious, stubborn and proud, demanding complete loyalty from his subjects, especially from his closest friends. The world of this story is a treacherous one, with allies swiftly turning into enemies, and although Luke’s courage and warlike nature leads him to victories, his desire to avenge any perceived slight, any hint of disloyalty, leads him down a dark path… Consisting of three books, The Prince in Waiting, Beyond the Burning Lands and The Sword of the Spirits, this is an epic series, which cleverly threads in mythology (there’s a witty use of the tale of Tristan and Isolde at a key moment in the story), religion and science into a post-apocalyptic world. Some of the other tribes and settlements Luke encounters on his various journeys are unsettling and sometimes plain bizarre. I found Christopher’s portrayal of a violent fractured society, with dangers around every corner, compelling and the story is taut and brisk, with new wonders, and new horrors, emerging with each chapter. If you’re a fan of post-apocalyptic science fiction / fantasy, then this is certainly a series you would enjoy – I wouldn’t rate it quite as highly as John Christopher’s incredible Tripods Trilogy (which I have written about previously in this blog) but it is a fascinating companion piece and a worthwhile read in its own right. If you’re interested in finding out more about John Christopher / Sam Youd, I strongly recommend visiting the Syle Press website, which is packed with information and resources about the author and his books. Magic. The very word itself conjures so many different ideas, images and symbols. The story of magical beliefs is as old as the history of humanity itself, and it is this vast tapestry Chris Gosden explores in his excellent book, The History of Magic – From Alchemy to Witchcraft, from the Ice Age to the Present. The scope of the book is remarkable; we journey from the Ice Age, through the earliest civilisations in Egypt, Mesopotamia and China, across the Eurasian Steppe to explore shamanism, the magics of the Americas, Africa and Australia, and the development of magic in Europe, all to the modern day. It could be easy to get lost in such an enormous canvas and there is much for the reader to absorb, but I never found the book less than highly readable. The inclusion of tables outlining the chronology of the periods being discussed adds valuable and helpful context, especially when the historical timescales are often lengthy. Through an anthropological and archaeological study of magic, Gosden argues passionately (and persuasively) for a change of mindset, rejecting the long-embedded views of magic (especially in Western perspectives) as primitive and backward. Drawing on practices and beliefs from throughout human history, Gosden asserts magic encourages a holistic, connected view of humanity, linking us to our planet through moral and practical relationships. As is outlined in the book, human understanding of the mechanics of the world and the universe is often considered to be divided into three key areas of thought, starting with magic, before moving through religion to reach science, an evolution in thought. Gosden argues instead the three strands of thought form a ‘triple-helix’ and have always been interconnected and inter-reliant.

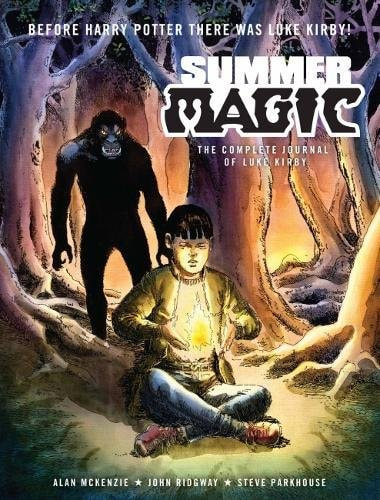

Every chapter of The History of Magic brings fresh discoveries and intriguing characters from the past (from kings, shamans, witches and many more), and underlines how magic has and remains part of the human experience I found The History of Magic a thought-provoking and spellbinding read. Written with the greatest of respect for magical practices and beliefs, it is a book of deep scholarship and of relevance to our times, and one I am sure I will return to for pleasure and inspiration. If you’re interested in the history of magic, I would also strongly recommend The Book of English Magic by Philip Carr-Gomm & Richard Heygate, a gripping and fascinating work. In the summer of 1962, with his mother recuperating from an illness, young Luke Kirby is sent to stay with his Uncle Elias, (who Luke has never met) in a village called Lunstead. Elias soon reveals himself to be a magician, and he is keen to pass his skills onto his nephew. But as Luke begins his magical apprenticeship, a deadly horror reveals itself… Written by Alan McKenzie, and illustrated by John Ridgway and Steve Parkhouse, Summer Magic: The Complete Journal of Luke Kirby is a collection of tales (originally printed in 2000AD), which coalesce into an overall story arc. The stories are varied, for example: The Night Walker, where Luke must confront a vampire; Sympathy for the Devil, where Luke travels to hell (an unnervingly original version of the underworld) in search of his father; and (possibly my favourite in the book) The Old Straight Track, which delves deep into British mythology and folklore, becoming a memorable folk horror tale infused with paganism, during which Luke—guided by the mysterious alchemist called Zeke— travels through a landscape marked by ley lines, stone circles and long barrows. For me, there are echoes of the work of Alan Garner with the close connection between the landscape and the characters. Summer Magic is a compelling collection, with stories that in places pack a disturbing punch. Throughout the book, the beauty and mystery of the English countryside is beautifully evoked through the writing and the stunning artwork. And beneath that beauty, and within the sleepy streets of the villages and little towns, true horrors lurk… Through all the stories run themes of death, family and horror, and as Luke develops his magical and alchemical skills, he learns that all actions, however well-intentioned, have consequences. Within Summer Magic, there is more than a little sense of the challenging, hard-edged fare of 1970s British cinema and TV (this is definitely a story for the Scarred for Life generation). Summer Magic: The Complete Journal of Luke Kirby is a great collection—a coming-of-age tale but with a 2000AD edge, an excellent example of the dazzling range of creativity that has poured from the comic’s pages over the decades. If you’re read and reread all of the Harry Potter books, or just finished binge-watching series 4 of Stranger Things, you will find much to enjoy in this dose of Summer Magic. If you want to find out more about Summer Magic: The Complete Journal of Luke Kirby, I'd recommend this excellent short introductory video made by 2000AD: |

Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed